Tags

A Martian Odyssey, Aladdin, conlang, Robwords, science fiction, Stanley Weinbaum, The Lord of the Rings, Toki Pona, Tolkien

Welcome, as always, dear readers.

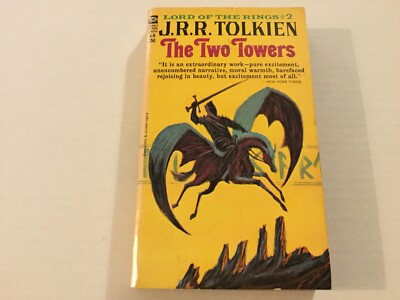

I’ve read and reread Tolkien since the surprising appearance of this—

and the two volumes which followed–

which got me hooked and, as the (rather tired) saying goes, the rest is history—although I much prefer the genie’s words at the end of Disney’s Aladdin

“…ciao! I’m history! No, I’m mythology!”

as JRRT himself said of creating a language:

“As one suggestion, I might fling out the view that [in] the perfect construction of an art-language it is found necessary to construct at least in outline a mythology concomitant…because the making of language and mythology are related functions.” (“A Secret Vice” in J.R.R. Tolkien, The Monsters and the Critics, 210)

In all of those readings, however, I’ve never quite believed something which Tolkien wrote—and more than once—that:

“The invention of languages is the foundation. The ‘stories’ were made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse.” (taken from letter to the Houghton Mifflin Co., June, 1955, Letters, 319)

Gollum? Saruman? Grishnakh and Ugluk? Treebeard? Sam? All created only so that they could speak JRRT’s languages? Such vivid major and minor characters—surely there was also a pure pleasure not only in having them talk, but in what they said and what effect their talk—and actions—had on the ‘stories’?

I can certainly believe, however, that the languages were a major feature of JRRT’s making of Middle-earth—just the essay I quoted above—“A Secret Vice”– would show you just how devoted Tolkien was to languages and their creation, or look up “Languages” in the Index to Letters

and you’ll find two columns and a little more (pages 667-669) of references to languages, name-formation, Quenya vs Sindarin, Dwarvish, the Black Speech, and much more. And, digging below the surface, you can find such details as Tolkien writing to a fan with the declension of two nouns in Quenya: cirya, “ship” and lasse, “leaf” (declensions are patterns of noun/adjective formation in which the functions of the words are shown by their endings—think of “whose” and “whom” in English as the last remnants of something which would earlier have look like this:

Nominative (shows subject): who

Genitive (shows possession): whose

Dative (indirect object): whom

Accusative (direct object/takes prepositions): whom

Ablative (would take some other prepositions—fell together with the accusative): whom

and there can be other endings—all called “case endings”—like the instrumental, the ending of which would tell you that the noun was being used as a means to do something, the locative, which indicates at what place something is, and the vocative, employed when you’re addressing someone/thing)

(see “From a letter to Dick Plotz, c.1967, Letters, 522-523)

Such profusion is in strong contrast to something which I discovered a week or two on YouTube.

One of the real pleasures I find there are the number of languages and essays about them available in great profusion. One of my current favorites is a feature called “RobWords”, which is written and presented by Rob Watts, its subjects tending to center around English, but touching upon German and French, among other topics, as well.

It’s a very informative and light-hearted site with occasional surprises, as I found with one entitled “The World’s Smallest Language”, which introduced a conlang (constructed language—in fact, just like Tolkien’s languages), but with an extremely simple grammar and an initial vocabulary of 120 words: “Toki Pona” (you can see the episode here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PY3Qe_b9ufI )

The inventor, Sonja Lang, is, not surprisingly, a linguist, combining her knowledge of world languages with her own creations—something you might guess from the name of the language itself: “toki” coming from the language “Tok Pisin”—that is, “Talk Pidgin”—“pidgin” meaning a kind of trade language—and “pona” coming from Latin “bonus –a –um”—“good”. (More about pidgins here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pidgin and Tok Pisin here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tok_Pisin )

Here’s how Lang explains it:

“Toki Pona was my philosophical attempt to understand the meaning of life in 120 words.

Through a process of soul-searching, comparative linguistics and playfulness, I designed a simple communication system to simplify my thoughts.” (Toki Pona The Language of Good, Preface)

And simple it is: things which appear in Indo-European languages like grammatical gender (whether a noun is masculine, feminine, or neuter—not important in English, but necessary, for instance, in language descended from Latin—Italian, French, Spanish, Catalan, Portuguese, and Romanian), plurals, case endings (see above), definite and indefinite articles (the/a/an in English) verb tenses, even more than one form for a verb—are all gone. Sentence formation basically follows English, which is Subject, Verb, Object (SVO in linguistic terms—“Cats [subject] drink [verb] milk [object]”)—but use the link above to learn more and be entertained by a bit of a catchy pop song in Toki Pona. If you want more about its grammar, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_PgytSj-YVE and, if you go to YouTube, there are many more places to visit. If you watch these two videos, you’ll see that that simplicity might easily lead to vagueness (something which “RobWords” points out), but, for a fluent speaker, with an imagination, perhaps it’s less vague than may seem at first. For example, watch this speaker demonstrate how you can create the term “video game” using only the readily-available vocabulary: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/z2ltEHfgR2g

Tolkien had been a learner and admirer of an earlier conlang: Esperanto (if you don’t know about it, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Esperanto and https://esperanto.net/en/ ) and I wonder what he would have made of Toki Pona? As a number of its words are derived from a language he loved, Finnish, I think that we might not be surprised if he found Toki Pona fun (see: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/UoVTWjMrlp4 for a list of parallels between the two languages)—although he probably wouldn’t be able to resist adding to that 120-word basic vocabulary.

But all of this raises the question: just how many words do you need to communicate?

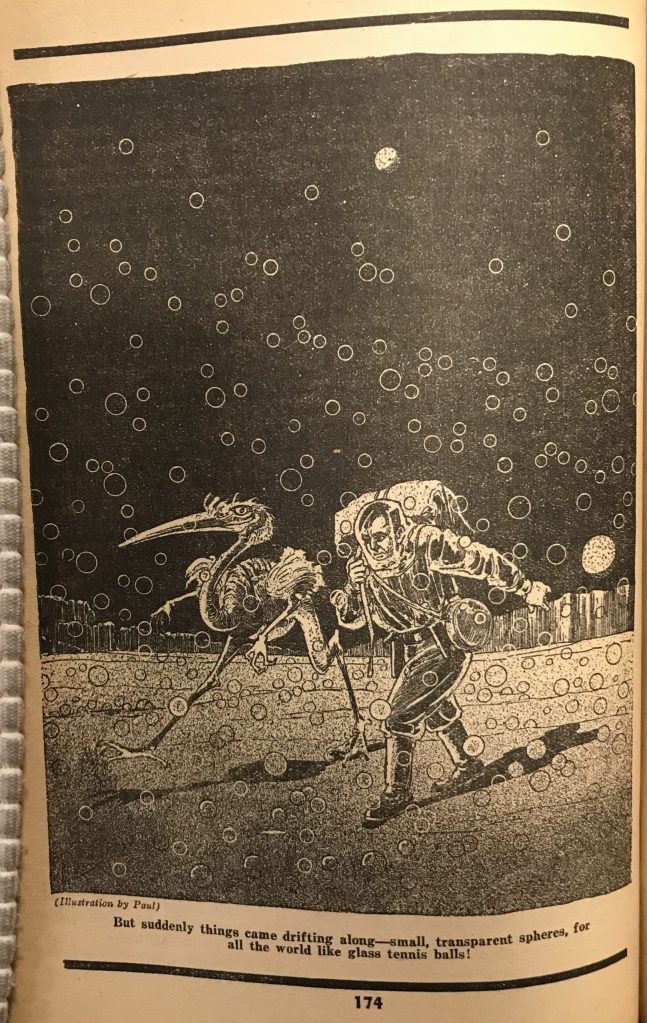

In my science fiction reading, I’ve found one ingenious answer in a short story by Stanley G. Weinbaum, “A Martian Odyssey”, published in the July, 1934 issue of Wonder Stories. For another wonder, it was his first published story in what was, unfortunately a brief career, Weinbaum dying in 1935. (You can read more about him here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanley_G._Weinbaum )

In this story, the main character, Jarvis, is one of a 4-man expedition, the first to reach Mars (and this is a Mars with Martian gravity, but also with a thin, breathable surface layer of oxygen). While exploring, his ship crashes and he’s stranded many miles from where the rocket which brought the crew to Mars, the Ares, has landed. While hoping that the others will search for him, he sets off to walk back towards the Ares and, in the process, rescues a local, whom he calls “Tweel”, as he can’t really pronounce the local’s actual name, that being a loose approximation. He attempts to communicate, using a few words, based upon the setting, and then a little math, and it’s clear that the local understands some of what he tries to do, but, interestingly, while “Tweel” can speak a little of what Jarvis tries to convey, Jarvis has no luck—and doesn’t even really try—to speak the other’s language. So, with about half-a-dozen words between them, they set off together on Jarvis’ original journey, meeting strange creatures—and a deadly one—on the way.

I won’t do a summary beyond this as, if you read this far and you’re interested in languages or science fiction, or both, you’ll want to read the story for yourself: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/23731/23731-h/23731-h.htm

Thanks, as ever for reading,

Stay well,

mi tawa (“Goodbye” in Toki Pona—simply meaning “I’m going”, although I’d prefer to say the “hello” greeting, powa tawa sina—“peace be with you”),

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS Weinbaum wrote a sequel to “A Martian Odyssey” which, if you enjoyed that story, you can read here: https://gutenberg.org/cache/epub/22301/pg22301-images.html

of which there are seemingly many surviving in several media. Older yet are the Greek masks, the images of which survive in many fewer images, mostly on pots.

of which there are seemingly many surviving in several media. Older yet are the Greek masks, the images of which survive in many fewer images, mostly on pots.

Why are they so scary? Well, for one thing, the clothing is bright and festive, but the face is dead-white and corpse-like, therefore giving a mixed signal of merriment and death at the same time. Perhaps these contradictions should have made the stepmother less trusting (it certainly made

Why are they so scary? Well, for one thing, the clothing is bright and festive, but the face is dead-white and corpse-like, therefore giving a mixed signal of merriment and death at the same time. Perhaps these contradictions should have made the stepmother less trusting (it certainly made