As ever, dear readers, welcome.

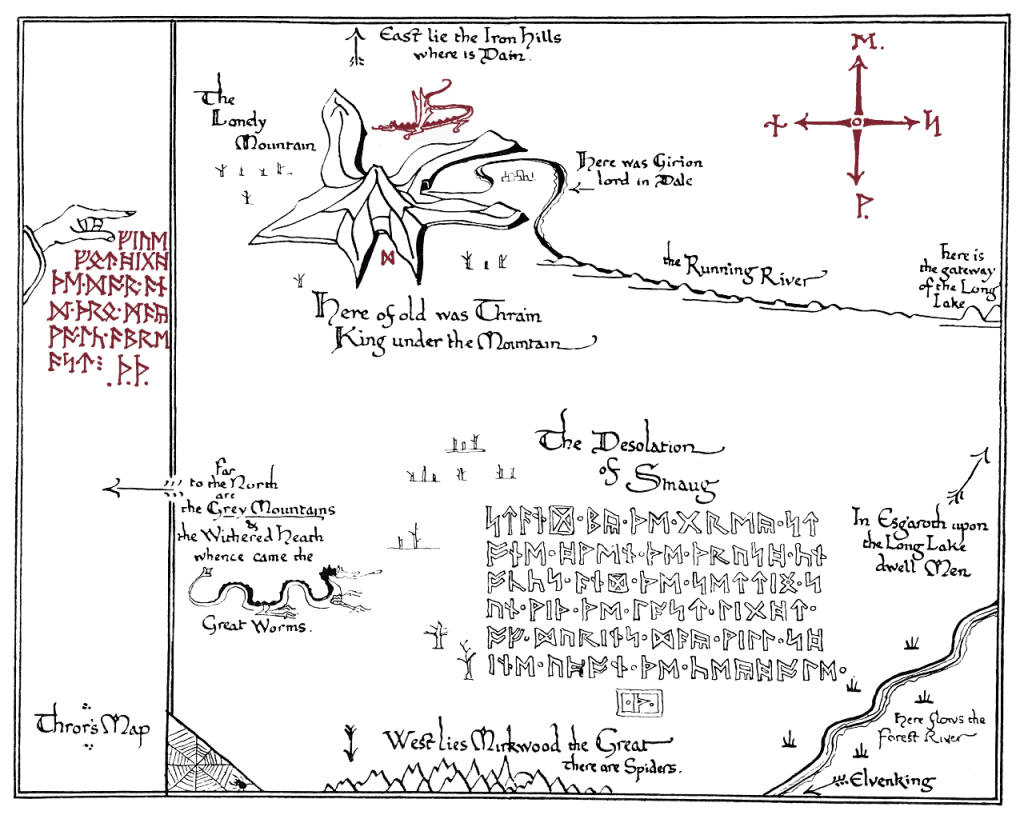

Sometimes, for all of his hard work, something which Tolkien planned simply never appeared, at least in his lifetime.

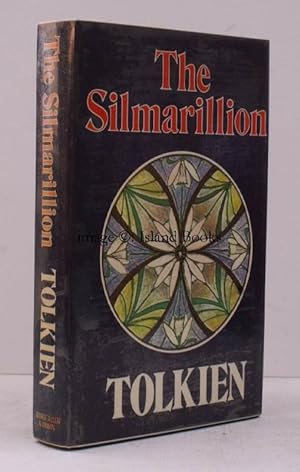

The biggest and most obvious of these is The Silmarillion,

with which he struggled for years, even flirting with an American publisher, Collins, when his Hobbit publisher, Allen & Unwin, agreeable to The Lord of the Rings, proved unwilling to publish it along with that work, which only appeared, edited by Christopher Tolkien, in 1977.

An earlier disappointment had been a smaller one, but JRRT put the same amount of creative energy and effort into it which he applied to much grander works:

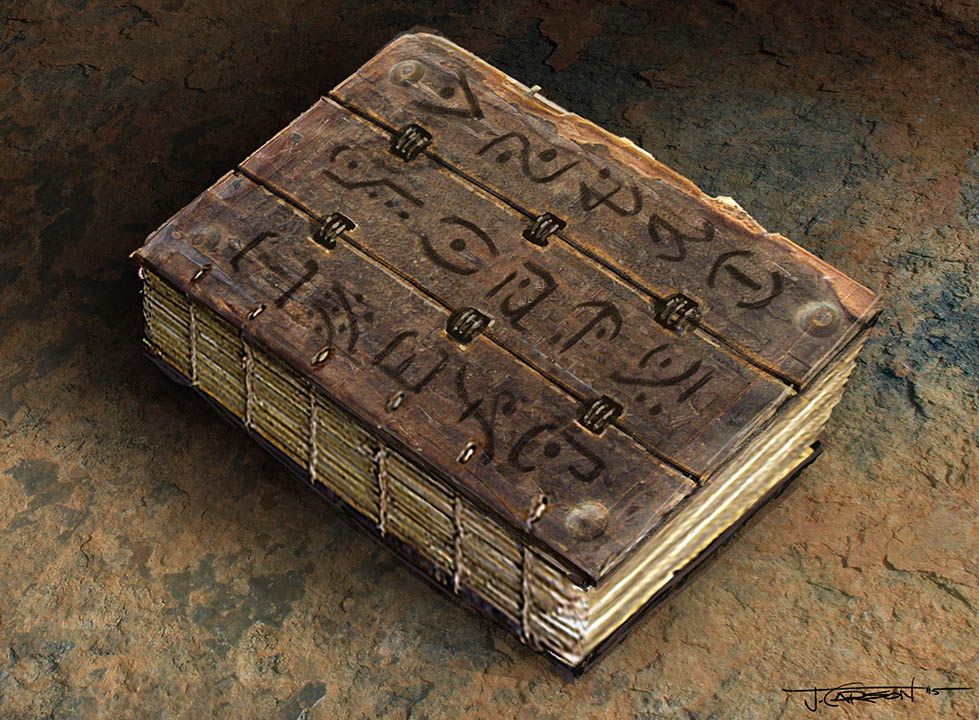

“There were many recesses cut in the rock of the walls, and in them were large iron-bound chests of wood. All had been broken and plundered; but beside the shattered lid of one there lay the remains of a book. It had been slashed and stabbed and partly burned, and it was so stained with black and other dark marks like old blood that little of it could be read. Gandalf lifted it carefully, but the leaves cracked and broke as he laid it on the slab. He pored over it for some time without speaking. Frodo and Gimli standing at his side could see, as he gingerly turned the leaves, that they were written by many different hands, in runes, both of Moria and of Dale, and here and there in Elvish script.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 5, “The Bridge of Khazad-dum”)

This is the “Book of Mazarbul”, which Gandalf describes as “a record of the fortunes of Balin’s folk”—that is, of the dwarves who followed Balin to repopulate the mines of Moria about 30 years before the beginning of the final adventure of The Ring. This is a story with an unhappy ending, of course, as Balin and all of his people were eventually killed by orcs who themselves came to repopulate Moria and it ends with those terrible words, “they are coming”.

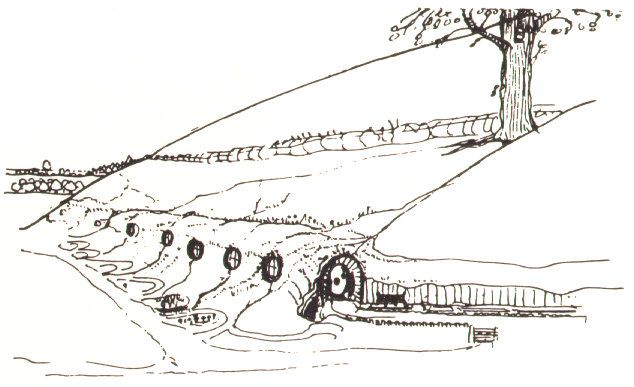

Had he had the time, I wouldn’t be in the least surprised to find that Tolkien would have reconstructed the entire book, but, in a fit of realism, he confined himself to three pages, including that final page,

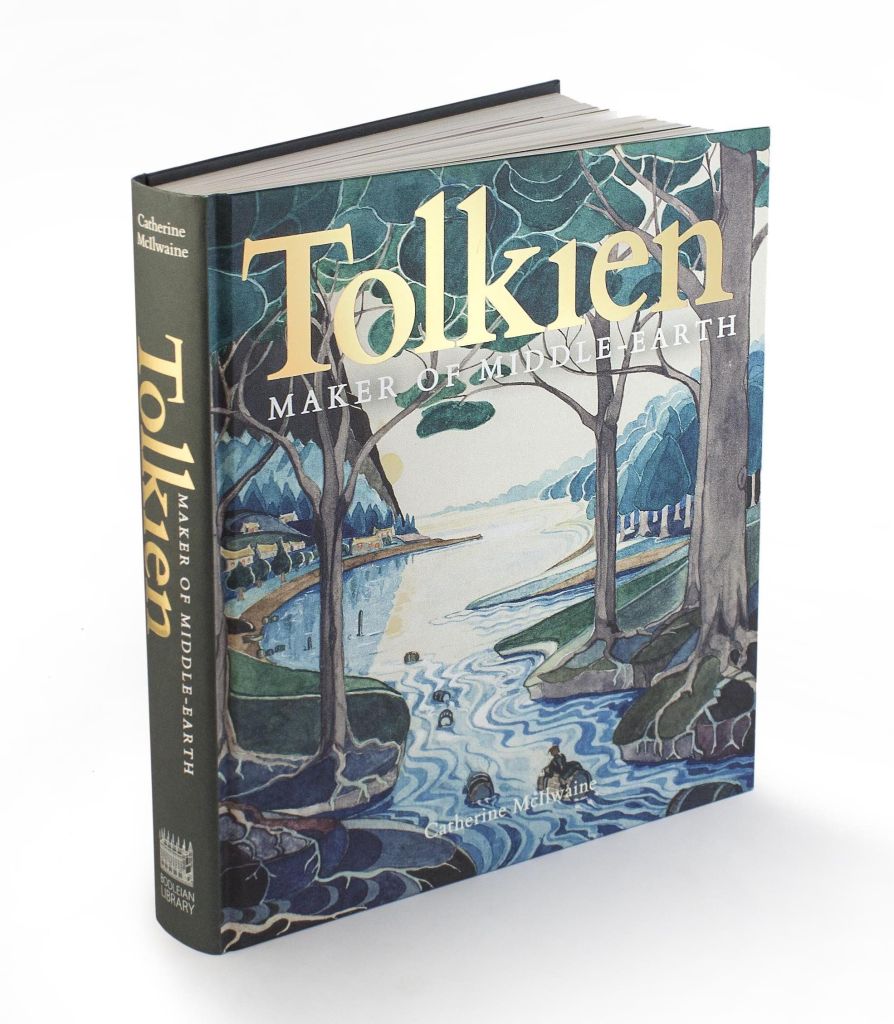

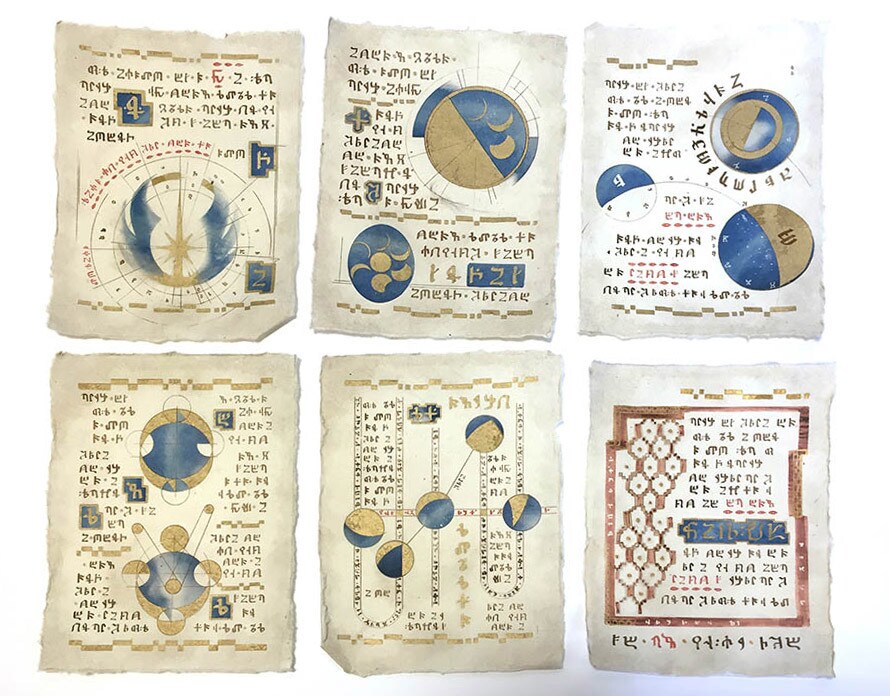

hoping to include them among the illustrations (maps, the Hollin gate of Moria, and the lettering on Balin’s tomb). This page shows his efforts, which including burning the pages with his pipe, punching holes in the margin to indicate where the pages would have been stitched to the binding, and staining them with red (I presume water color) to simulate blood. For all those efforts, however, the publisher informed him that including them in color would have been too expensive and so, like The Silmarillion, they only appeared after Tolkien’s death. (For images of all three pages—in color—and more details, see pages 348-9 of the highly informative Catherine McIlwaine Tolkien Maker of Middle-earth, published in 2018 by the Bodleian Library.)

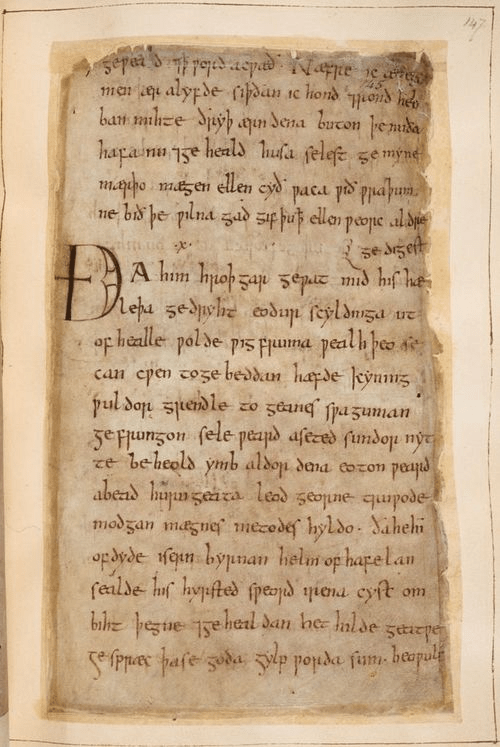

For someone who worked in Early English literature, models for his pages would have been easy to come by. Here’s the first page of his beloved Beowulf, from the manuscript called “Cotton Vitellius A XV”.

Though not “slashed and stabbed”, it was certainly “partly burned” in a great fire in 1731 which not only damaged this manuscript, but destroyed a number of others. (For more on the manuscript and on the poem, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nowell_Codex and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beowulf#External_links This is our only manuscript of the poem and I shake my head at the thought that, had the fire gone a little farther, we would have lost this wonderful piece of English poetry forever.)

So often, these postings are explorations of some of the many various sources which influenced and stimulated Tolkien, but I’ve recently come upon what I suspect might be the opposite.

In 2010, the director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, narrated a 100-part series on BBC Radio 4 entitled, A History of the World in 100 Objects, all drawn from the Museum’s vast collections. That same year, a companion book appeared.

It was a very clever idea (although it takes a moment to imagine how these objects were, initially, unseen, but only described) and soon there were a number of imitations, including this—

which recently came into my hands. What’s marvelous about this is that, in contrast to the British Museum book, which uses actual historical artifacts, everything in this book, beginning with the idea of Star Wars itself, is something creatively imagined, even if based on things from our own galaxy. It was, like the MacGregor, a fun read, but my attention was particularly caught by these—

“[Objects Number] 76 Ancient Jedi Texts”.

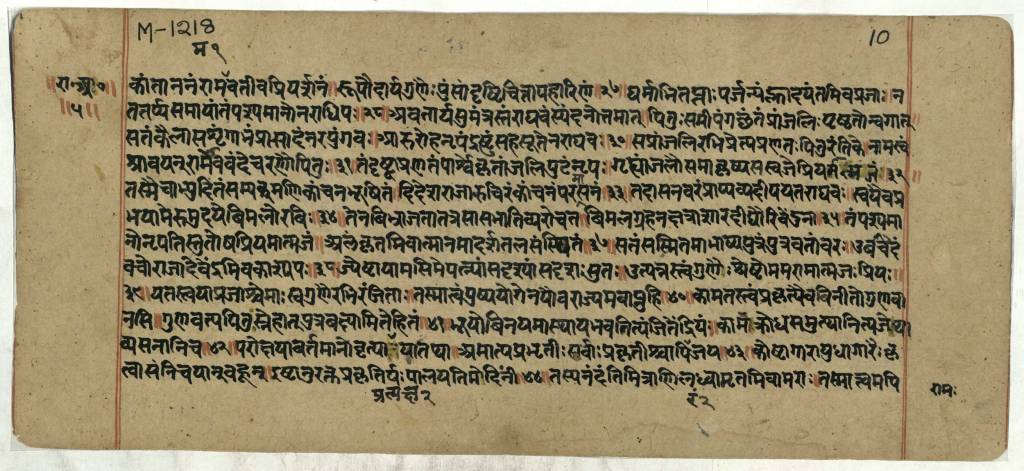

With names like “Aionomica” and “Rammahgon” (which immediately reminded me of that magical Indian epic, the Ramayana,

a story of a kidnapping, a demon king, and a rescue–an easy introduction would be this–)

they were, as the book’s text informs us: “Far from those exciting stories of lightsaber adventures…” but, instead, were meant “…to preserve the sacred knowledge of those most in tune with the nature of the galaxy.”

Interestingly, however, the “Rammahgon”

“…contains four origin stories of the cosmos and the Force…Recovered from the world of Ossus, the pressed red clay cover represents an omniscient eye referenced in a poem within. But between the wordplay and talk of battling gods, there lies real, indisputable knowledge that saved the galaxy from the Sith Eternal.”

The look of ancient wear and tear of these texts imitates manuscripts the study of which occupied Tolkien’s scholarly work for most of his life

and presented a model for his own imitation of pages from the “Book of Mazarbul”. Could it, in turn, have provided an inspiration for the creators of the “Jedi Sacred Texts”? And, considering the kinds of material found in the Silmarillion—foundation and stories of struggles between lesser gods and would-be greater ones and evil as great as the Sith–could we see another bit of earlier Tolkien influencing later Star Wars?

As always, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

Consider which texts you find sacred,

And remember that, as ever, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

If Neil MacGregor’s original series interests you, you can see/hear it here:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/about/british-museum-objects/