As ever, dear readers, welcome.

This posting came about because I was rereading Kipling’s Just So Stories (1902). In the last of the stories, at the beginning, I found this:

“There are three hundred and fifty-five stories about Suleiman-bin-Daoud: but this is not one of them. It is not the story of the Lapwing who found the Water; or the Hoopoe who shaded Sulieman-bin-Daoud from the heat. It is not the story of the Glass Pavement, or the Ruby with the Crooked Hole, or the Gold Bars of Balkis. It is the story of the Butterfly that Stamped.” (Rudyard Kipling, Just So Stories, “The Butterfly That Stamped” You can read the story here: https://archive.org/details/justsostories00kipl/page/n9/mode/2up in a 1912 American edition. A word of caution, however: sometimes Kipling’s language seems, to our ears, casually racist, but that was 1912 and, to my mind, doesn’t mar the stories in general, although, in 2024, it does stand out in an unpleasant way.)

It’s a trick I’ll bet you can spot immediately: a politician speaking about a rival, will say, “But I will not mention my opponent’s _________”—and you can fill in the blank with anything negative which might come to mind. It’s a very old rhetorical trick—so old that the Greeks used it (hence that “paraleipsis”, from the verb paraleipein, “to leave aside”) and the Romans, who were careful students of Greek rhetoric, employed it in turn (hence “praeteritio”, from praeter, “beside” and ire, “to go”).

This mentioning, but then withholding information, has a cousin in a form of this trick used by story-tellers in the West since the Greeks and clearly still in use in Victorian/Edwardian times by Kipling. Consider, for example, Book 11 of the Odyssey. Here, Odysseus, at the court of Alkinoos, (that’s al-KIH-noe-os),

is relating his visit to the Otherworld

and, at one point, lists a whole series of famous women he sees there, from Tyro, who slept with Poseidon and produced Pelias and Neleus—Pelias being the evil uncle who sends Jason off after the Golden Fleece—

(a wall painting from Pompeii—this is the moment when Pelias recognizes Jason by a prophecy which has warned him to beware of a visitor wearing only one sandal)

to Alkmene, mother of Herakles,

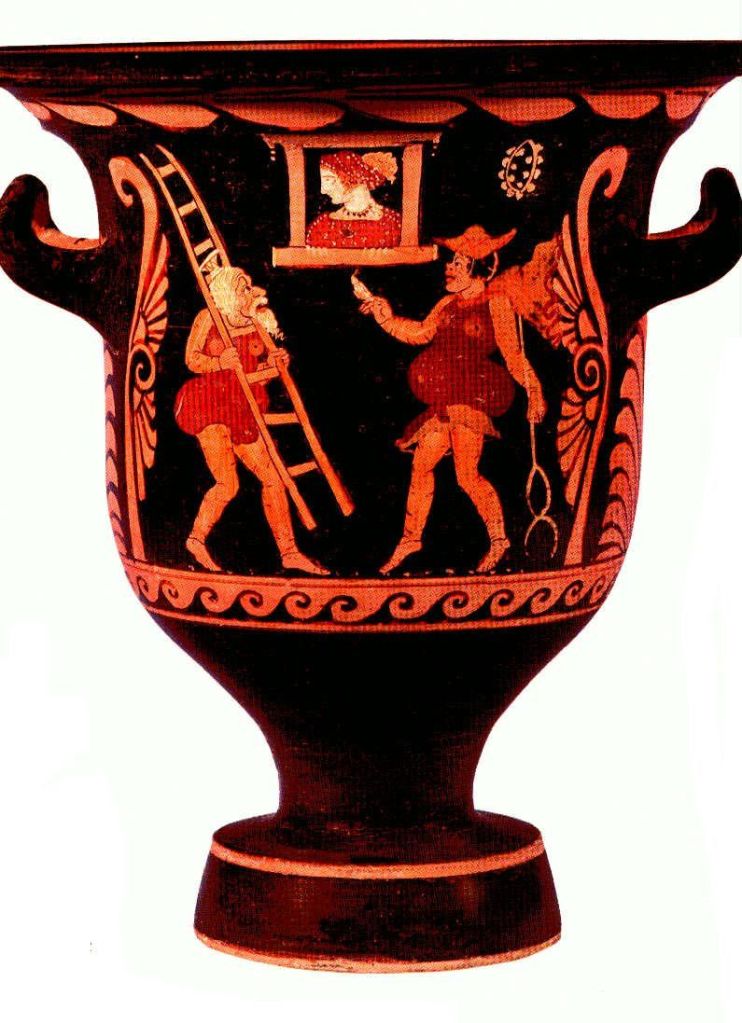

(a South Italian comic pot, in which Zeus, aided by Hermes, is trying to get into Alkmene’s window)

to Ariadne, daughter of Minos, who helped Theseus against the Minotaur in the Labyrinth.

(Ariadne gave Theseus a ball of string to help him get back from the maze. You can read the whole list here: Odyssey, Book 11, lines 235-330–https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0136%3Abook%3D11 )

Each time, there’s a mention, but no story is ever gone into in detail.

Each of the women is given a kind of mini-biography (mostly about how the majority of them slept with Zeus), with a little detail, and the whole list resembles a well-known, now-fragmentary work once attributed to the early Greek poet, Hesiod, called “The Catalogue of Women”, also known by the first word of each entry in the catalogue as Eoiai, which we can translate as “[or] her like”. (You can read an extensive article about this here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catalogue_of_Women and you can read the collected fragments here: https://www.theoi.com/Text/HesiodCatalogues.html )

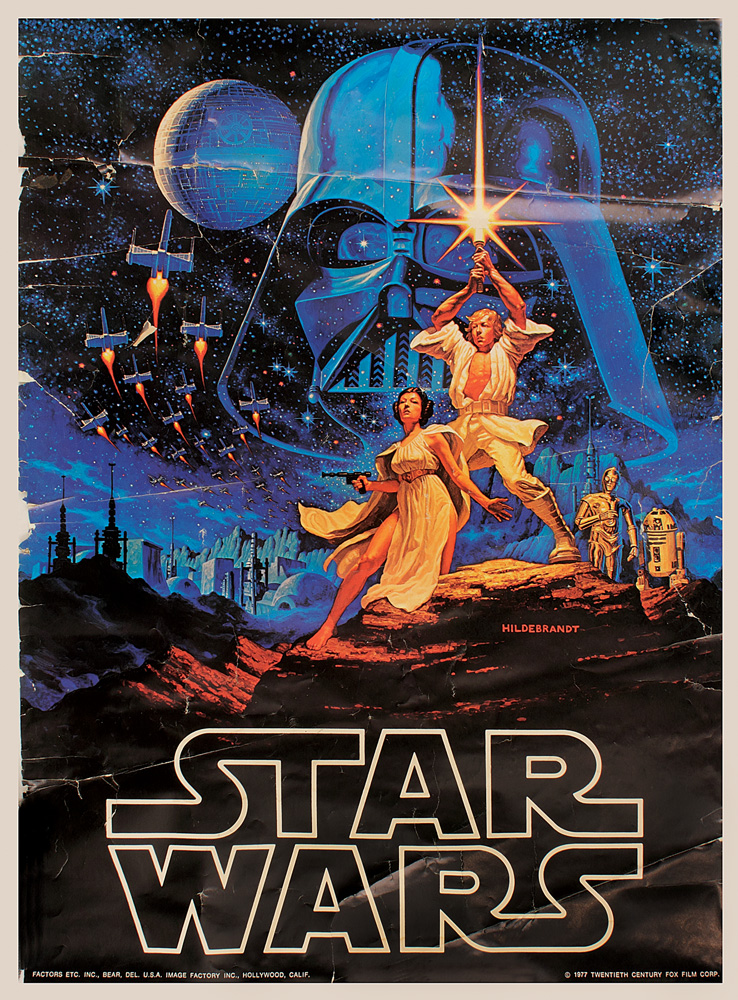

Assembling and preserving the past became an important feature of the later Greco-Roman world, but, thinking about the mini-catalogue in the Odyssey, and the fact the poem itself is a compilation of the works of earlier oral singers, I wonder if what we’re seeing here doesn’t have other purposes, first, the survival of a kind of boast on the part of those early singers—“Look what other cool stories I know”—and, second, a tease—“and wouldn’t you like to hear those next?” as if what we’re reading now wasn’t a sort of “trailer”, like those we still see in movie theatres, as well as on-line. (As one easy example, here’s the original trailer for Star Wars: A New Hope, from 1977: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1g3_CFmnU7k If you haven’t seen this, you’ll be amazed at how “crude” it now seems when, in 1977, it was the beginning of a new age of technological adventure-telling which is still with us, the carefully-built and filmed tiny models of then now replaced by often-astounding CGI now.)

(You’ll notice, by the way, that this poster was designed by the same Hildebrandt brothers who also gave us so many wonderful Tolkien images.)

“The Butterfly That Stamped and the two catalogues from the Greek past brought another “here are stories—but I’m not going to tell you” to mind:

“ One winter’s night, as we sat together by the fire, I ventured to

suggest to him that as he had finished pasting extracts into his

commonplace book, he might employ the next two hours in making

our room a little more habitable. He could not deny the justice of

my request, so with a rather rueful face he went off to his bedroom,

from which he returned presently pulling a large tin box behind him.

This he placed in the middle of the floor, and squatting down upon

a stool in front of it he threw back the lid. I could see that it was

already a third full of bundles of paper tied up with red tape into

separate packages.

‘There are cases enough here, Watson,’ said he, looking at me

with mischievous eyes. ‘ I think that if you knew all that I have in

this box you would ask me to pull some out instead of putting

others in.’

‘These are the records of your early work, then?’ I asked. ‘ I

have often wished that I had notes of those cases.’

‘Yes, my boy; these were all done prematurely, before my

biographer had come to glorify me.’ He lifted bundle after bundle,

in a tender, caressing sort of way.

‘They are not all successes, Watson,’ said he, ‘but there are some pretty little problems among

them. Here’s the record of the Tarleton murders, and the case of

Vamberry the wine merchant, and the adventure of the old

Russian woman, and the singular affair of the aluminium crutch,

as well as a full account of Ricoletti of the club foot and his

abominable wife. And here—ah, now ! this really is something a

little recherché.’ “ (Arthur Conan Doyle, “The Musgrave Ritual”—one of my all-time favorite Holmes stories, collected in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes, 1894, which you can read in the 1894 edition, with the original illustrations, here: https://ia801306.us.archive.org/27/items/memoirsofsherloc00doylrich/memoirsofsherloc00doylrich.pdf )

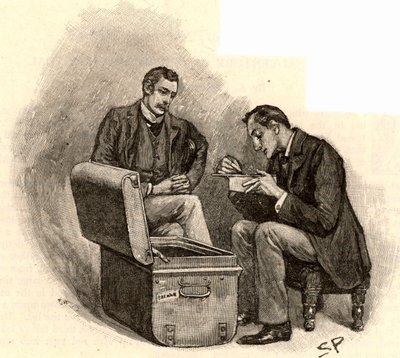

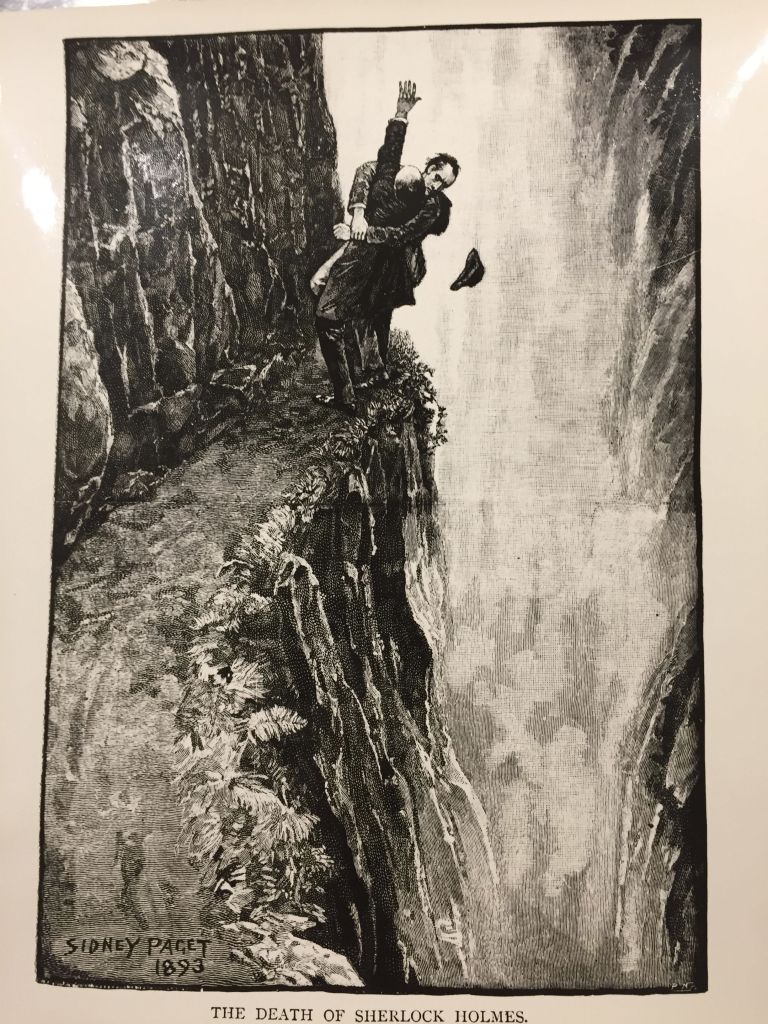

(one of those original illustrations by Sidney Paget)

And here we see again the same trick—and this is only one of a number of occasions in the Sherlock Holmes stories when a subject is mentioned—but there is no story to be found to follow it. (See for much more: https://www.ihearofsherlock.com/2016/01/the-unpublished-cases-of-sherlock-holmes.html )

As Conan Doyle came to dislike Holmes and even tried to kill him off in 1893 (see “The Final Problem” in the same volume as “The Musgrave Ritual”)

(another Sidney Paget)

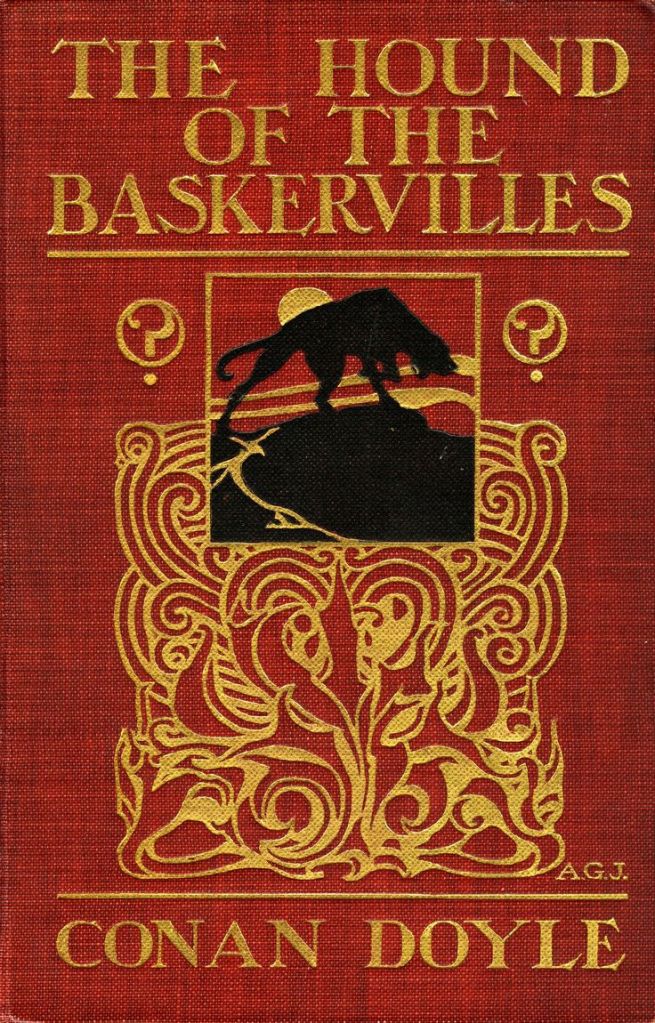

it’s puzzling that he would do this to his readers—why would he suggest more stories to come?–but then, in 1901, he brought Holmes back in The Hound of the Baskervilles (originally published in The Strand Magazine, but you can read it in its 1902 book form here: https://gutenberg.org/files/2852/2852-h/2852-h.htm ),

so, for all of his mixed feelings about his detective, perhaps that earlier quotation from “The Musgrave Ritual” is appropriate:

‘There are cases enough here, Watson,’ said he, looking at me

with mischievous eyes. ‘ I think that if you knew all that I have in

this box you would ask me to pull some out instead of putting

others in.’

And, as Conan Doyle’s last Holmes story appeared in 1927 (“The Adventure of Shoscombe Old Place” collected in The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes, and you can read it here: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/69700/pg69700-images.html#chap11 ) perhaps, even to Conan Doyle, there was always the chance for more.

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

For lack of space, I admit that I’ve left out such works as Filbert L. Gosnold’s “The Mystery of the Exploding Pants” as well as many other examples,

But remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

In closing, I have what might be a final example, of which there is, alas, no chance of more, as teasing as the initial mention is:

“He is surer of finding the way home in a blind night than were the cats of Queen Beruthiel.” (The Lord of the Rings, Book Two, Chapter 4, “A Journey in the Dark”)

Although Tolkien never mentioned those felines again in print, we know a little more about the Queen and her cats from what Christopher Tolkien calls “a very ‘primitive’ outline, in one part illegible” (see Unfinished Tales, page 419), including “She had nine black cats and one white…setting them to discover all the dark secrets of Gondor”, but, as the author himself wrote, in a letter to W.H. Auden:

“I have yet to learn anything about the cats of Queen Beruthiel.”

having prefaced that with, “These rhymes and names will crop up; but they do not always explain themselves.” (letter to W.H. Auden, 7 June, 1955, Letters, 419)

Or is this like Conan Doyle, using Sherlock Holmes to drop a teasing hint of more to come—which never did?

PPS

If you have access to it, you might enjoy this lively BBC series by the English historian, Lucy Worsley, on Conan Doyle’s love/hate relationship with Sherlock Holmes–