Welcome, dear readers, as always.

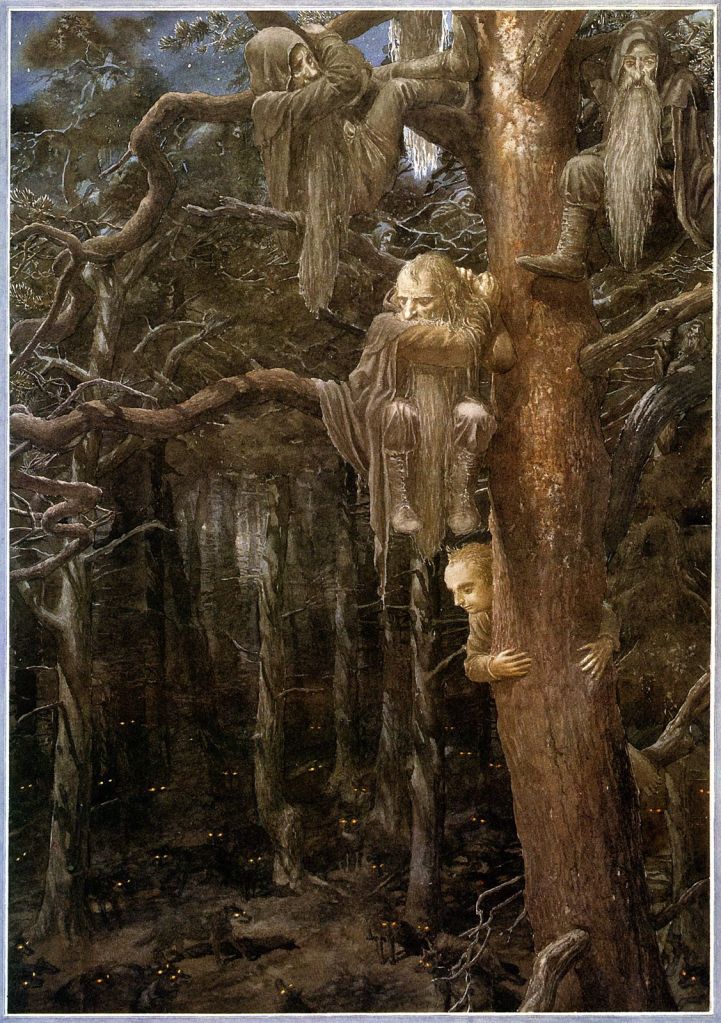

“All of a sudden they heard a howl away down hill, a long shuddering howl. It was answered by another away to the right and a good deal nearer to them; then by another not far away to the left. It was wolves howling at the moon, wolves gathering together!” (The Hobbit, Chapter 6, “Out of the Frying Pan Into the Fire”)

(Alan Lee)

In his invaluable The Annotated Hobbit,

Douglas Anderson points to a letter by Tolkien suggesting an influence, if not inspiration, for this scene of wargs (i.e. wolves) vs treed dwarves (and hobbit), as JRRT tells us:

“Though the episode of the ‘wargs’ is in part derived from a scene in S.R. Crockett’s The Black Douglas, probably his best romance and anyway one that deeply impressed me in school-days, though I have never looked back again. It includes Gil de Rez as a Satanist.” (“from a letter to Michael Tolkien…sometime after Aug.25, 1967”, Letters, 550)

Published in 1899, The Black Douglas,

Is one of a series of Scots historical novels by S(amuel).R(utherford). Crockett (1859-1914),

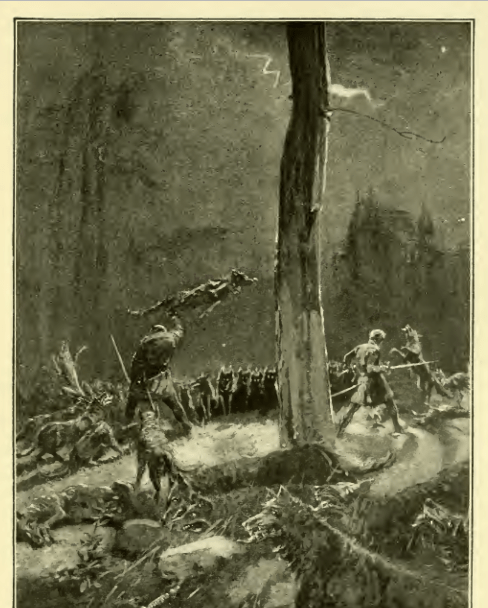

based upon actual events—in this case, it has, as a basis, the short life and judicial murder of William, the 6th Earl of Douglas and his younger brother, David, in 1440. It also has supernatural elements, however, including the sinister (but historical) figure of Gilles de Rais (c.1405-1440–Tolkien was clearly spelling from memory), one-time companion of Joan of Arc, who appears to be a werewolf, and, it’s a scene where the protagonists are attacked by werewolves

to which JRRT was referring—although the three don’t climb trees, but put their backs to them to fight on the ground, killing many of their attackers (and not being rescued by eagles—it’s Chapter XLIX and you can read it here: https://dn790000.ca.archive.org/0/items/blackdouglas00croc/blackdouglas00croc.pdf ).

Wolves—or wargs—as we see in The Hobbit, are pack animals.

Crockett imagined even werewolves as behaving like the wolves they turn into and this led me to a question which occurred when, recently, as part of an exercise in story-telling, I asked a class to tell me the story of “The Three Little Pigs”.

I’m sure that you know it, with its typical for Western fairy tales pattern of 3s: porcine architecture—straw,

sticks, bricks–attempts by the wolf to enter, replies by the pigs, subsequent action by the wolf and his parboiled demise.

Because of its simplicity and that pattern, it’s very useful as a subject for helping students to learn how stories work and how even such a simple story is built upon such basic narrative principles as foreshadowing and repetition to build tension.

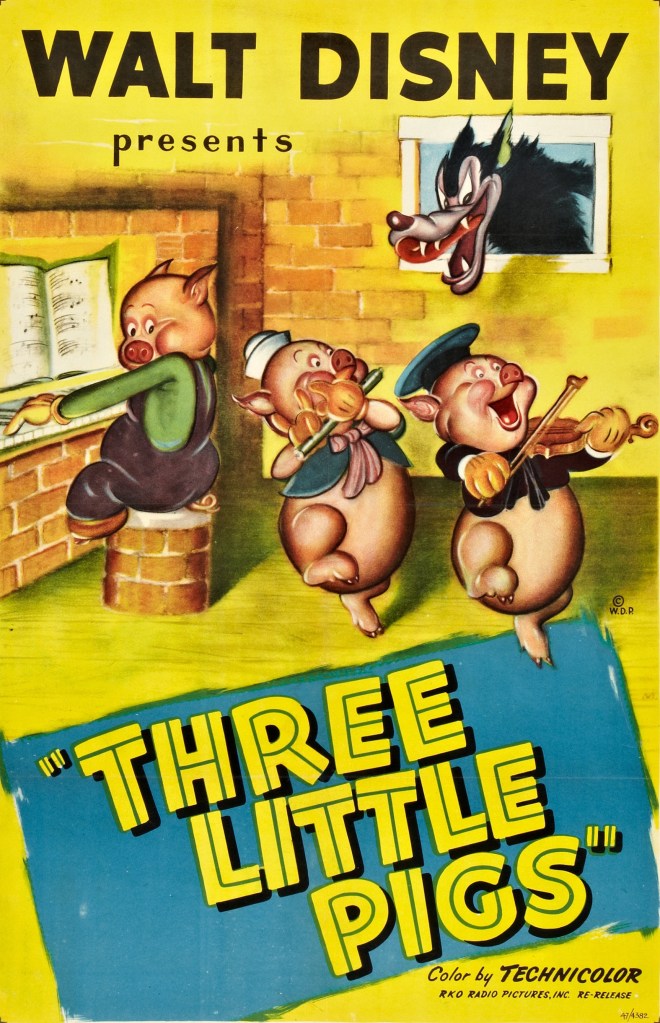

But, the 3 pigs sing mockingly in the 1933 Disney version,

“Who’s afraid of the big, bad wolf,

Big, bad wolf,

Big, bad wolf?

Who’s afraid of the big, bad wolf?

Tra la la la la!”

(There’s actually a much longer song and you can read it here: https://www.lyrics.com/lyric/27101857/Disney/Who%27s+Afraid+of+the+Big+Bad+Wolf and hear and see it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=leAh00n3hno )

and that made me notice something odd: not “Big, bad wolves”—what happened to the pack?

The idea of the “lone wolf” turns up in other fairy tales—think of “Little Red Riding Hood” for example,

(Perhaps my favorite illustration, by Gustave Dore—LRR seems to have a rather skeptical look—perhaps because in the version Dore illustrated, the last line of the story is: “Et en disant ces mots, le méchant loup se jeta sur le petit Chaperon rouge, et la mangea.”—“And, in saying these words, the wicked wolf threw himself upon Little Red Riding Hood and ate her.”)

where a single wolf meets Red, and the perhaps less familiar “The Wolf and the Seven Kids”.

(This is by a well-known Victorian illustrator, Walter Crane, 1845-1915, from an 1882 collection of the Grimm fairy tales which you can see here: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Household_stories_from_the_collection_of_the_Bros_Grimm_(L_%26_W_Crane)/The_Wolf_and_the_Seven_Little_Goats You can also read a translation at this site, which is specifically devoted to the works of the Grimms: https://www.grimmstories.com/en/grimm_fairy-tales/the_wolf_and_the_seven_little_goats )

Traditional fairy tales all have variants—sometimes numerous ones—and some appear even on a world-wide basis, like “Cinderella” (see an ancient Chinese version here: https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-myths-legends/fish-wish-your-heart-makes-2200-year-old-tale-chinese-cinderella-003506 ), but a little preliminary research has suggested another possibility.

Unlike other fairy tales, although scholars believe “The Three Little Pigs” to be an old story, I was surprised to learn that its first citation is only to an 1853 volume with a title which would not suggest that such a story would be included: English Forests and Forest Trees, Historical, Legendary, and Descriptive. It’s to be found in Chapter IX, “Dartmoor Forest” and, even more surprising, the characters aren’t pigs, but pixies, the villain of the piece isn’t a wolf, but a fox, and the houses are made of wood, stone, and iron. You can read it here: https://ia601307.us.archive.org/13/items/englishforestsa01unkngoog/englishforestsa01unkngoog.pdf on pages 189-190.

The version familiar to most of us first appears in the fifth edition of James Halliwell-Phillipps’ The Nursery Rhymes of England (1886), in which the third little pig (who survives, as his two brothers do not) has a lot more to do than in what must have been the simplified version I knew as a child—and this actually closely matches the Dartmoor version (except for the pixies and the fox). You can read it here: https://archive.org/details/nurseryrhymesofe00hall/page/36/mode/2up on pages 37-41. (For an entertaining essay on Halliwell-Phillipps and his work, see: https://reactormag.com/questionable-scholars-and-rhyming-pigs-j-o-halliwell-phillipps-the-three-little-pigs/ )

It’s admittedly just a guess on my part, Halliwell-Phillipps doesn’t credit a source, and, instead of a fox as the villain, there’s a wolf, but both stories, have the same pattern of threes, although building materials differ, and the three pixies have a different identity, but what we see here is the same story, which made me wonder:

- Did “pixies” become (possibly through mishearing of an oral telling) “pigsies”—that is, “little pigs”?

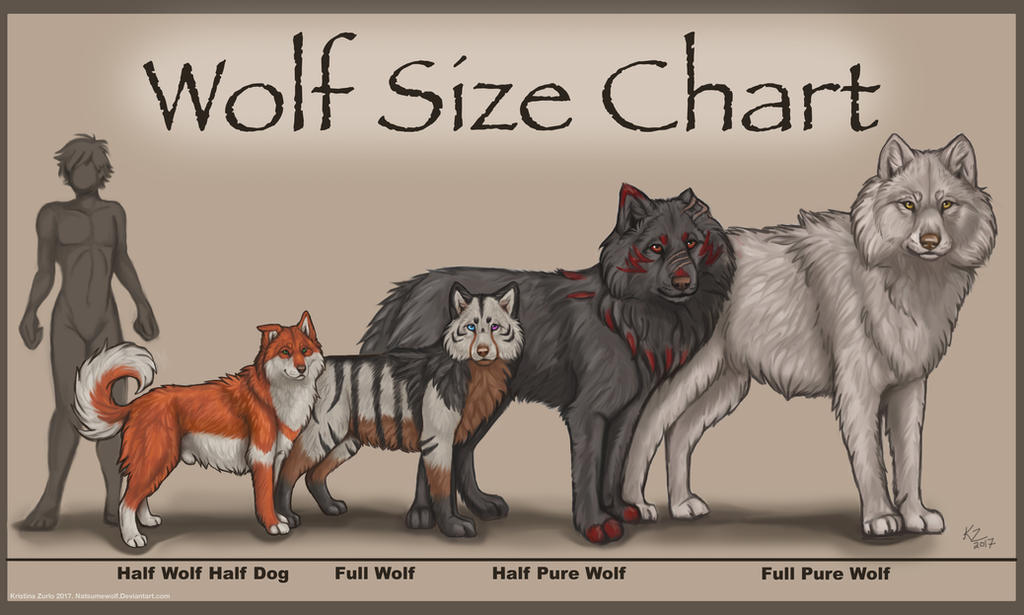

- Did the fox become a wolf because wolves can be quite large

(by NatsumeWolf—you can see more of her art here: https://www.furaffinity.net/gallery/natsumewolf/ )

and therefore more menacing in a story than a diminutive, but tricky, fox?

As well, that wolf in “Little Red Riding Hood” appears in Charles Perrault’s late-17th century story collection, Histoires ou Contes du Temps passe, first translated into English in the early 18th century, appearing, as well, along with “The Wolf and the Seven Kids”, in the Grimms’ early 19th century Kinder und Hausmaerchen, first translated into English in the 1820s, both being, therefore, readily available. So, could that frightening wolf from other stories perhaps have been leaning over Halliwell-Phillipps’ shoulder, pushing him to replace the fox, even as he turned pixies into pigsies? After all, he had nothing to lose but his pack…

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

If threatened by a wolf, try to out-fox him,

And remember that there’s always

MTCIDC

O

PS

For another, rather eerie story with—well, no spoiler alert, just read it: https://ia601303.us.archive.org/8/items/thetoysofpeacean01477gut/1477-h/1477-h.htm

This is by HH Munro, 1870-1916, who used the pen name “Saki”. I’ve mentioned him before, but I’m sure to mention him and his witty and sometimes weird short stories again in the future.