As ever, dear readers, welcome.

“Cependant les fées commencèrent à faire leurs dons à la princesse. La plus jeune lui donna pour don qu’elle serait la plus belle personne du monde ; celle d’après, qu’elle aurait de l’esprit comme un ange ; la troisième, qu’elle aurait une grâce admirable à tout ce qu’elle ferait ; la quatrième, qu’elle danserait parfaitement bien ; la cinquième, qu’elle chanterait comme un rossignol ; et la sixième, qu’elle jouerait de toutes sortes d’instruments dans la dernière perfection. Le rang de la vieille fée étant venu, elle dit, en branlant la tête encore plus de dépit que de vieillesse, que la princesse se percerait la main d’un fuseau, et qu’elle en mourrait.”

“Nevertheless the fairies began to make their gifts to the princess. The youngest gave her as a gift that she would be the most beautiful person in the world. The next, that she would have the soul of an angel. The third, that she would have an admirable grace in everything which she would do. The fourth that she would play all manner of instruments to the utmost perfection. The turn of the old fairy being come, she said, shaking her head more in spite than from age, that the princess would pierce her hand on a spindle and that she would die of it.” (My translation, as with all of the text in this posting, based upon Feron’s 1902 edition of the Les Contes de Perrault which you can read here: https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Contes_de_Perrault_(%C3%A9d._1902)/La_Belle_au_Bois_dormant )

You know this story—although you may know it by its English name, “Sleeping Beauty” and not by its original name “La Belle au Bois Dormant”—the “Beautiful Girl in the Sleeping Forest”—although that translation is wonderfully—and a little testily–argued over here: https://forum.wordreference.com/threads/la-belle-au-bois-dormant.3158165/ For all that people joust over whether that present participle/adjective, “dormant” can modify “Belle”, I prefer the idea that, as Beauty has fallen asleep, so the whole world around her has joined in the enchantment, as the story says—and so even the woods are drowsing till the prince arrives.)

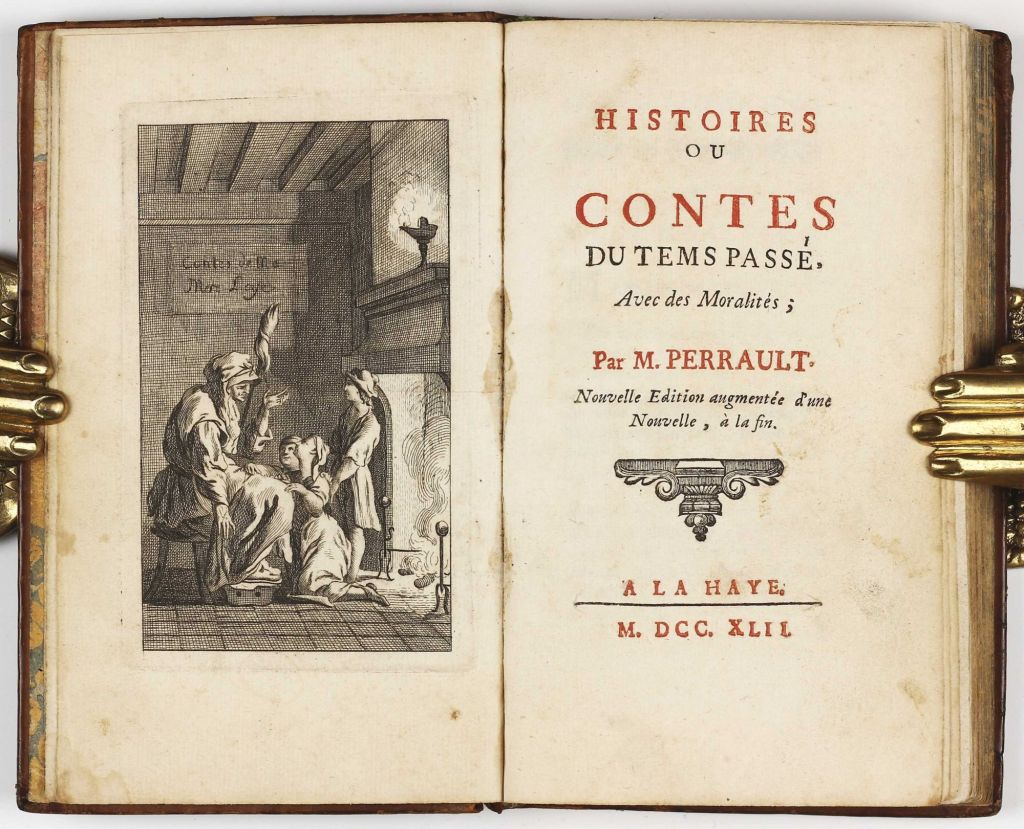

This story first appeared in Charles Perrault’s (1628-1703)

1697 collection Histoires ou Contes du Temps passé, avec des moralites—“Stories or Tales of Past Time, with Morals”, which sounds pretty dry—until you reach the subtitle: Les Contes de ma Mere L’Oye—“The Tales of My Mother Goose” and suddenly we’ve passed into another Time Past entirely.

(As you can see, an early edition—1742—but not a first)

I’ve always loved the story, but, when I was small, there was one thing which I didn’t understand— what was a “fuseau”—a “spindle”?

In my last posting, we had been briefly in Sam Gamgee’s uncle Andy’s rope walk

where we had been talking about how rope

is made, with likening the twisting of the fibers

to that of making thread.

(If you’d like to know more about making rope, have a look at this very informative WikiHow feature: https://www.wikihow.com/Make-Rope )

The simplest way to do this is to use a drop spindle—and here’s that “fuseau”–which allows gravity to do much of the work for you—

(Here’s the whole spindle)

(And here’s a WikiHow on spinning thread—which includes both a drop spindle and a spinning wheel: https://www.wikihow.com/Spin-Wool And there’s a YouTube video imbedded to make the process clearer.)

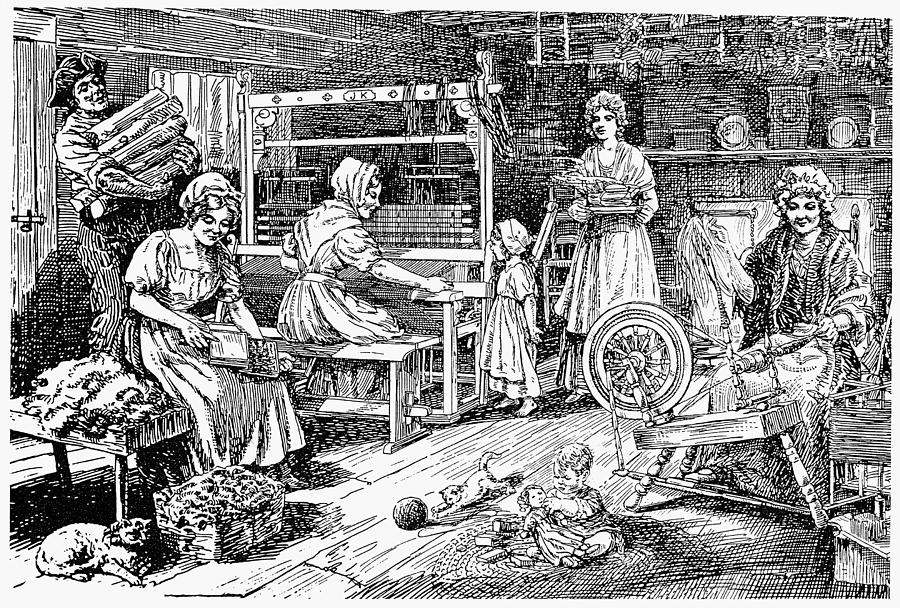

This is only a later part of the process of making cloth, which begins, of course, with shearing a sheep.

Then the fleece needs to be cleaned and the fibers need to be organized, with a pair of carding combs—

but here’s the whole process, in an 18th-century setting.

It’s a very labor-intensive process, as you can imagine, and you can see why the Industrial Revolution had, among its earliest inventions, the “Spinning Jenny”, which allowed one person to use a simple machine to produce numerous spools of thread at the same time, where a previous spinster (meaning someone who spins, not an unmarried woman, necessarily) could only produce one spool at a time and, at the time, it was said that it took five spinsters to keep a weaver busy.

(There was no “Jenny” by the way—it’s really “ginny”—18th-century Northeast English for “engine”—that is, in period technology, “machine”.)

In the story:

“Le roi, pour tâcher d’éviter le malheur annoncé par la vieille, fit publier aussitôt un édit par lequel il défendait à toutes personnes de filer au fuseau, ni d’avoir des fuseaux chez soi, sur peine de vie.”

“The king, to try to avoid the curse pronounced by the old fairy, immediately had an edict published by which he forbade anyone from spinning with a spindle, nor to have spindles in the home, on pain of death.”

But, inevitably—this is a fairy tale, after all—when she is 15 or 16, the princess, exploring a family country house, discovers a room in which an old woman is using a spindle (and, surprisingly, unlike that which our suspicious modern minds would expect, the old woman is an innocent, as the text says that she simply hadn’t heard of the king’s proclamation) and, piercing her hand, the princess simply falls victim to the curse—and the counter-spell which puts her to sleep.

Why a spindle? I’m sure that there are all sorts of Freudian explanations for this, but what I imagine Perrault—or whoever may have told the tale which he had once heard—if there ever was a real “ma Mere L’Oye”—thought was that, in the world of royalty, where clothes magically appeared in the hands of your servants,

(a much later image, but you get the idea)

a spindle might have seemed like a pretty—and novel—toy, as the princess exclaims, seeing the old woman at work:

“ ‘Ah ! que cela est joli !’ reprit la princesse ; ‘comment faites-vous ? donnez-moi que je voie si j’en ferais bien autant.’ “

“ ‘How pretty that is!…’How do you do it? Give it to me so that I may see if I may do it as well.’ “

And, reaching for it, as she’s a little “etourdie”—“scatterbrained” (or, more gently, “thoughtless”)—

“elle s’en perça la main et tomba évanouie.”—“she pierced her hand and fainted.”

Now as the youngest fairy, who has hidden behind a curtain, sensing trouble when the old fairy appears, has decreed, a century will pass, and the country house and all in and around it—including the forest which surrounds it– will sleep.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

Avoid antagonizing elderly fairies,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

In this season of Tchaikovsky’s “Nutcracker”, don’t forget that he also wrote a “Sleeping Beauty” ballet, which has its own wonderful music, which you can hear—and see–here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w7qLg1lOfrw