As always, dear readers, welcome.

This summer, I read a very interesting article on the possibility (I think probability) of a complex language of sperm whales (here is the BBC article: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20240709-the-sperm-whale-phonetic-alphabet-revealed-by-ai and there’s a very detailed scientific essay, but actually quite followable, as it’s well written and defines its vocabulary on the subject here: file:///C:/Users/twb/Downloads/s41467-024-47221-8.pdf ).

When I think of whales, 3 come readily to mind from literature. The first is the creature who swallows Jonah (although it is described as piscem grandem, a “big fish” in Jerome’s translation, which a whale isn’t, although ancient people probably weren’t aware of the difference—the Greek version says ketos megas, “big sea monster”).

(This is from a mosaic found on the floor of a synagogue at Huqoq, in 2017. For more on the discovery, see: https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/news/huqoq-mosaics-jonah-and-the-whale-the-tower-of-babel/ I like this depiction because of its vaguely comic air—Jonah being swallowed by a fish which is being swallowed by a fish which is being swallowed by a fish, like something out of Finding Nemo.)

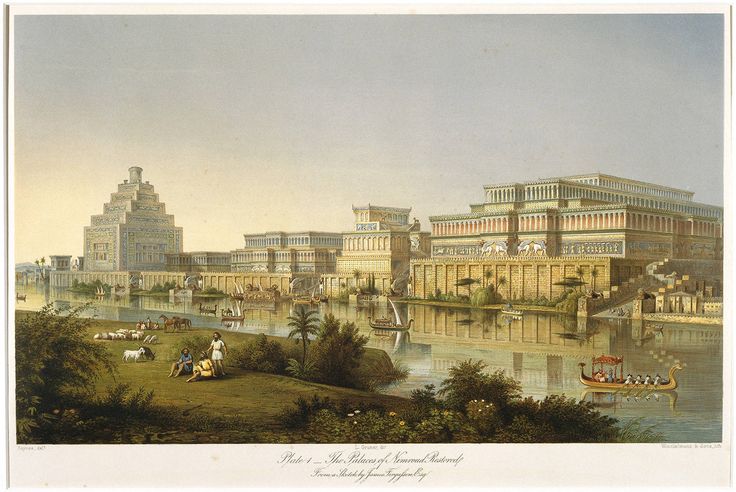

But the story begins in Nineveh, the capital of the Neo-Assyrian empire.

(A very genteel 19th-century reconstruction—for more early drawings of Nineveh and its remarkable reliefs, see Austen Henry Layard, 1817-1894, The Monuments of Nineveh, 1853, here: https://archive.org/details/the-monuments-of-nineveh.-from-drawings-made-on-the-spot/page/n1/mode/2up Layard was the first serious 19th-century archaeologist to dig extensively at the site, sending back heaps of his discoveries to the British Museum, where they remain today. He’s also a very good writer and, if you’re interested in the history of archaeology, you may enjoy his Nineveh and Its Remains, 1867, here: https://archive.org/details/ninevehanditsre03layagoog/page/n6/mode/2up For a quick little piece on Layard and the British Museum see: https://smarthistory.org/assyrian-lamassus-in-victorian-britain/ )

According to the story as translated by Jerome, Dominus (“the Lord”) was not pleased with the city, saying to Jonah that he should go there and inform the people that ascendit malitia eius coram me “its wickedness has come up into my presence”—and, knowing other instances of when something like this has happened, Nineveh is in for destruction unless—and that’s why Jonah is sent. Instead of obeying, however, Jonah skips town, hops on a ship, and suddenly (are we surprised?) there’s a tremendous storm, as well as dialogue between the ship’s captain, the crew, and Jonah, who admits that he’s the reason and that, if they want calm weather, they need to throw him overboard. The sailors are decent folk, and, at first, refuse, but, Jonah prevailing, over he goes and meets that piscis grandis.

(An ambo—a lectern from which readings are delivered—this one dates c.1130AD and is found in the church of Saint Pantaleone in Ravello, Italy)

By repenting, he’s saved, goes to Nineveh, warns the people and they, and even the king, change their ways, and there’s a happy ending—although the ending of the book itself seems rather abrupt and the book in general has been the center of scholarly discussion for centuries. If you’d like to read Jerome’s Latin translation, which is my go-to for the Bible in general, see: https://vulgate.org/ot/jonah_1.htm For more about Jonah, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jonah although this article needs a little editing. On the Book of Jonah see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Jonah It’s interesting that, in Western sailor’s lore, a “Jonah” is a person on board a ship who brings misfortune. There’s a horrible example of this in Peter Weir’s outstanding film, Master and Commander, 2003, if you like first-rate adventure films—highly recommended!)

I suspect that my first whale and its occupant were well known to the author of my second story, “Carlo Collodi” (real name: Carlo Lorenzini, 1826-1890),

who originally published his serial of the burattino (“puppet”) who could talk and move on his own in a children’s magazine, Il Giornale dei Bambini (“Children’s Magazine”) in 1881. (The Wiki article needs to be corrected here, saying that it was first published in Il Corriere dei Piccoli–something like “The Little Ones’ Messenger”—which was not founded till 1908. For an article about the Giornale, see: https://www.academia.edu/7325693/Ferdinando_Martini_e_la_direzione_del_Giornale_per_i_Bambini_in_alcuni_documenti_inediti_1881_1889_ )

It is always one of the great pleasures of researching and writing this blog that I’m always taught something new and, in the case of that original short story of Pinocchio, it was a little shocking. As someone who first met Pinocchio, Collodi’s creation, in a later revival of Disney’s 1940 Pinocchio,

I’d always imagined that, once more united with his creator, Geppetto, Pinocchio would become a real boy and live happily ever after. In that serial, however, two tricksters, a cat and a fox, in the disguise of “assassins” attempting to steal money from Pinocchio, hang him, and that, apparently, was where the serial ended—until the publishers wanted the story to continue and so Pinocchio was rescued by an agent of his patron, the Blue Haired Fairy, and the story went on—to (more or less—lots more complications than in the film) the ending which I had always known: Pinocchio is eventually rewarded by becoming that real boy. (For a rather grim essay on the original form of the story, see: https://slate.com/culture/2011/10/carlo-collodi-s-pinocchio-why-is-the-original-pinocchio-subjected-to-such-sadistic-treatment.html )

Collodi published the extended work in 1883

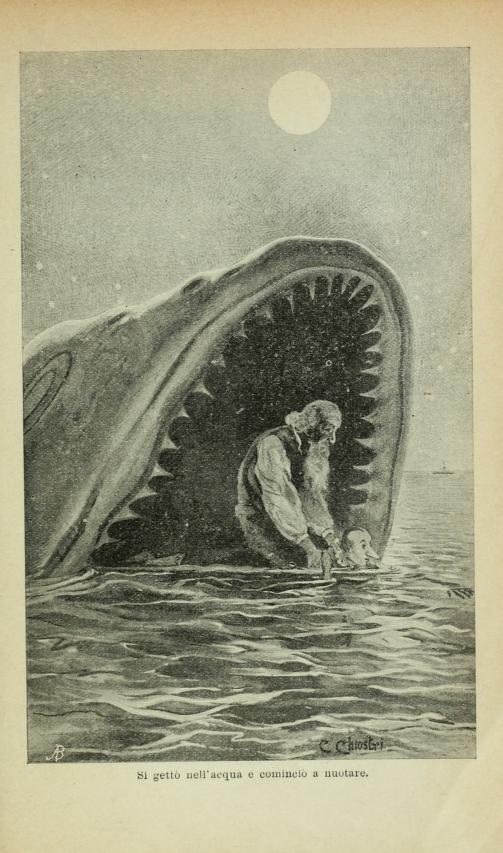

and, in its later chapters we see that Jonah motif appear again, when Pinocchio’s creator, Geppetto, seeking the lost Pinocchio at sea, is swallowed—along with his ship—by what the Italian text calls a pesce-cane, but which an early translator called a “dogfish”, although pescecane means “shark” in modern Italian (a “dogfish” is a gatttucio). Pinocchio rescues Geppetto

and proceeds on his way to his boy-metamorphosis (although he has to rescue the Blue Haired Fairy from poverty and illness before the final change). You can read the Italian here: https://archive.org/details/laavventuredipin00coll/page/n3/mode/2up and a 1904 translation into English here: https://archive.org/details/adventuresofpino00coll_4/page/n7/mode/2up Be warned, however, that there is a certain level of cruelty, particularly towards animals, in this story which would make me hesitate to read this to a modern child.

Again, as in the Jonah story, what I’ve always imagined as a whale (and so do Disney’s animators)

it seems to be everything but a cetacean (and, if you didn’t know that technical word for kinds of sea mammals, you can go back to the beginning of this posting and see where it comes from in Jonah’s swallower being called, in Greek, ketos megas),

but my third is very definitely a whale, although he only swallows a selection of his relentless pursuer (reminds me, of course, of Captain Hook, from Peter Pan, where the Crocodile there has swallowed one of Hook’s hands and now wants the rest).

It’s also a story, which, although I’ve read it twice, I can only point to, suggesting that, if you haven’t read it, you might try it, as, like War and Peace, it has the undeserved reputation of being a book more likely to be mentioned than actually read and as, over the years, War and Peace has become a favorite, a book which, every so often, I find that I just have to reread, I would say the same for this long, complex work.

(If you’d like to try War and Peace, I would recommend seeing this BBC production first. It encapsulates many of the longer story’s elements, and, as you’d expect from the BBC, it’s beautifully acted, and it’s visually beautifully realized.)

But my final whale is one of the principal characters (although spoken of, kept offstage till late in the book) of Herman Melville’s, 1851 novel.

It’s such a crazy mixture of archaic language, image, description, drama, philosophical/theological discussion that you might find it a bit like Finnegans Wake—an interesting idea, but difficult to digest (but definitely easier to follow—although, if you should try Moby Dick, I would recommend this to help you to visualize it—it may be a coloring book, but it’s extremely well detailed and drawn.)

Its whale and his pursuer, Captain Ahab, have been analyzed in every way possible—see this to read much more: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moby-Dick –and the critical library is now enormous, but I would say that, for all that it covers, in its chapters, everything you’d ever want to know about whales and whaling, among other things, at base, it’s a book about a mad obsessive, a man so fixed upon revenge that he’s willing to sacrifice everything to gain it, including his own life, strangled by his own harpoon line and dragged into the sea to follow the whale upon whom he’s sworn vengeance.

Here’s the book, if you’d like to try it: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/2701/pg2701-images.html#link2HCH0135 There is also an extremely useful site here: http://powermobydick.com/ which explains the many references which often seem to litter the pages, chapter by chapter.

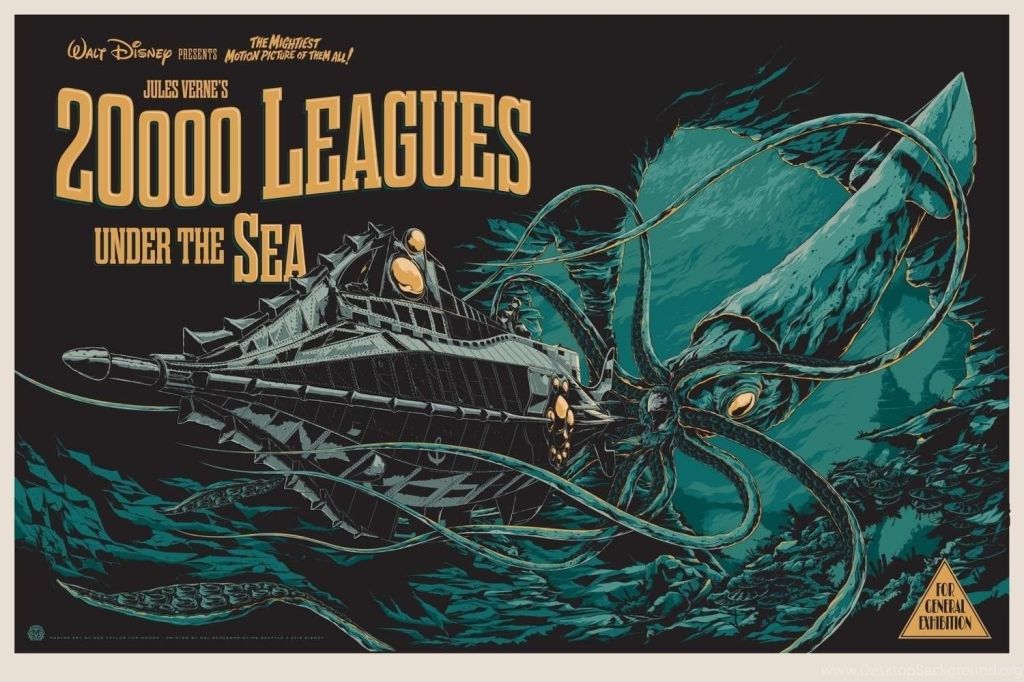

But this seems like such a grim ending that I’ll add this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AkjTGCrLvAU It’s Kirk Douglas, as harpooner Ned Land, in Disney’s 1954 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea,

singing “I’ve a Whale of a Tale”. This is a great adaptation of Jules Verne’s original, with an impressive Victorian submarine, the Nautilus. (Those thousands of leagues don’t mean deep, by the way, but long, as it describes the ranging ability of Captain Nemo’s ship.)

As always, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

Imagine not hunting whales, but chatting with them,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O