Tags

Boccacio, Elves, Horace Walpole, letters, Middle-earth, pleasaunce, Ranelagh Gardens, Roman de la Rose, Tolkien, Vauxhall Gardens

Dear readers, welcome, as always.

Because I enjoy reading letters from people in the past, I sometimes wonder from whom I would like to receive one—or more. Certainly from the 18th-century English literary man, Horace Walpole (1717-1797),

who is credited with writing the first “Gothic” novel—1764—and, on the title page of the 2nd edition of 1765 actually calls it one—

and who so loved what he understood to be the medieval past that he built himself a castle in a “Gothic” style, Strawberry Hill, which you can visit today as it’s being lovingly restored.

The letters are gossipy and often quietly humorous and have the sound of a real voice, which is one reason why I enjoy reading them. Here he is in 1760 complaining about the mail—

“I would give much to be sure those letters had reached you. Then, there is a little somebody of a German prince, through whose acre the post-road lies, and who has quarrelled with the Dutch about a halfpennyworth of postage ; if he has stopped my letters, I shall wish that some frow may have emptied her pail and drowned his dominions !” (letter to Sir Horace Mann, 14 November, 1760—this is #722 in Volume V of the 16-volume Oxford collection, which you can find here: https://archive.org/details/lettersofhoracew56walp/page/n7/mode/2up “frow” is Walpole’s spelling of Dutch huisvrouw, “housewife” and I suspect that the “pail” is more likely a chamberpot, from his tone–)

Certainly I would be glad to receive something from Emily Dickinson, 1830-1886, which might even include a poem, as hers sometimes did.

Like Walpole’s, these are missives full of a living—and like Walpole, sometimes skeptical and humorous—person. (There are two modern editions of the letters, the more recent just published last year, but you can get a sense of her for free from volume one of the first edition, from 1894, here: https://archive.org/details/lettersofemilydi00dick )

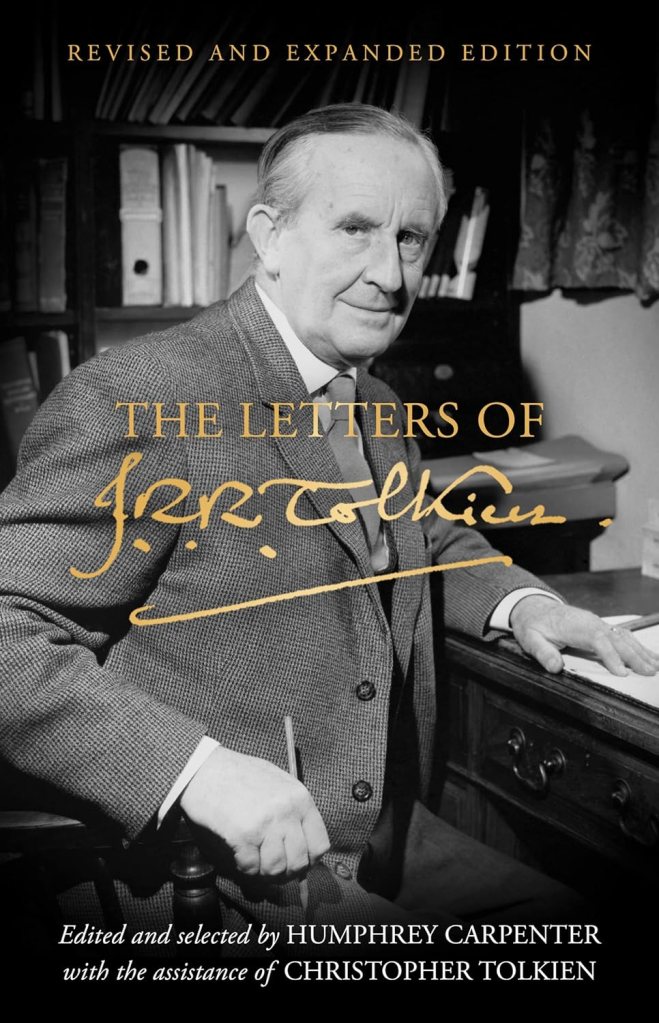

And, of course, letters directly from Tolkien, rather than being forced to read over his shoulder as we do with The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien,

would be wonderful, not only for their voice, everything from affectionate to outraged, but also because there may be something more, even perhaps something unexpected to be read in them, even if you’ve read the same letters more than once.

Just the other day, for example, I was thumbing through, looking for something else, and I came upon this:

“But the Elves are not wholly good or in the right. Not so much because they flirted with Sauron; as because with or without his assistance they were ‘embalmers’. They wanted to have their cake and eat it: to live in the mortal historical Middle-earth because they had become fond of it (and perhaps because they had there the advantages of a superior caste), and so tried to stop its change and history, stop its growth, keep it as a pleasaunce, even largely a desert, where they could be ‘artists’—and they were overburdened with sadness and nostalgic regret.” (to Naomi Mitchison, 25 September, 1954, Letters, 293)

What an interesting view of the Elves! And that’s another reason to read letters: you never know what you may learn and what may surprise you. In this case, we are given a very much more nuanced picture of Middle-earth than, say, The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings—and, in this case, a darker picture.

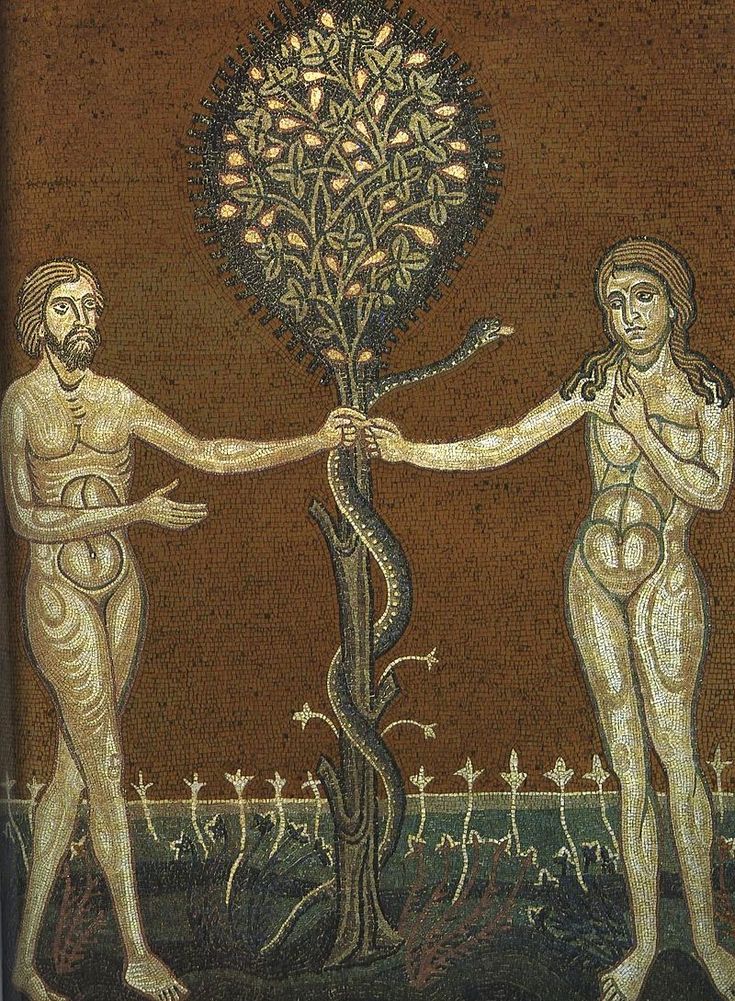

And one word in particular in this letter caught my attention: “pleasaunce”, which can mean a “pleasure garden”. Harkening back to Eden,

(Adam and Eve and a scaly friend from my favorite west-Byzantine mosaics in Monreale cathedral)

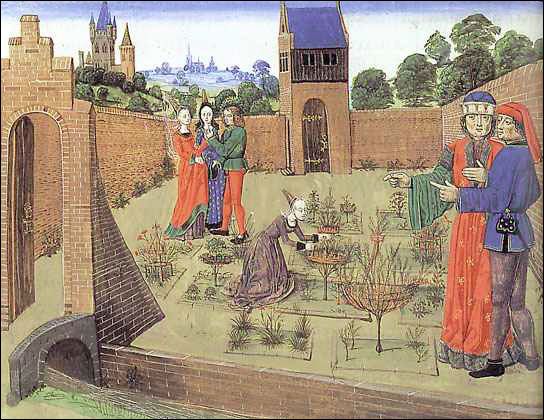

such places became a feature of medieval settings—both real and in literature—as we see in this depiction of the garden which is the scene of the opening of the 13th-century Roman de la Rose.

or Emilia in Theseus’ garden from Boccacio’s 14th-century Teseida.

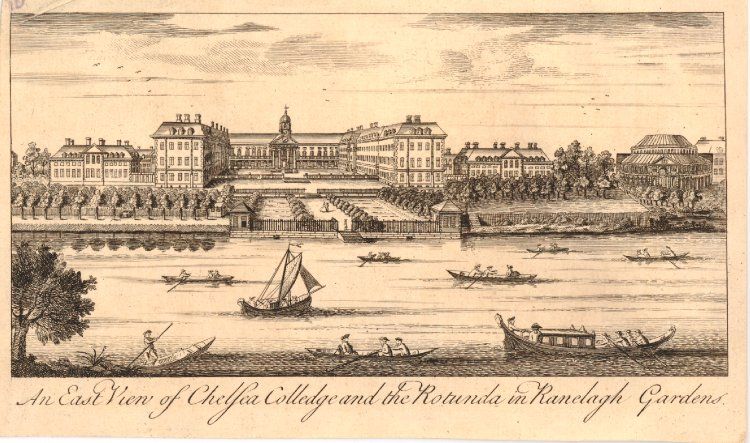

They reached big—commercial—time in 18th-century London, with the very elaborate Ranelagh Gardens

with its large and elegant rotunda, and famous organ (Mozart at 9 played a concert at Ranelagh)

and Vauxhall,

known for its long, green avenues, its music,

and for the suggestion of naughtiness in such a large, but shadowy place. (Although older, Vauxhall survived longer—its final closing came in 1859. For more on both Gardens, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ranelagh_Gardens and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vauxhall_Gardens )

A key feature of such places is the potential not only for including, but for excluding, as well. After all, because of their naughtiness, Adam and Eve were eventually barred from their pleasaunce,

(another image from Monreale)

medieval gardens had walls to allow for limited entrance (the protagonist of The Roman of the Rose has to have the help of a character called “Indolence” to get in), and Ranelagh and Vauxhall had gates and entrance fees, so it’s interesting to see what Tolkien means by his choice of word. As he says, his Elves had become “embalmers’, by which he means that they were like Egyptian mummifiers,

although their body was still alive, and their process was meant to stop history, not decay, and, at the same time, to change Middle-earth from something naturally progressing through time for all its inhabitants into a “pleasaunce”—an artificial walled pleasure garden for themselves, something frozen in time, in which they could enjoy themselves as if they were the sole owners and masters, including and excluding as they wished.

It would be easy to believe that Tolkien means by this to show the Elves as ultimately lordly and selfish and there is the suggestion of this—but there’s something more and I would suggest that this makes clear JRRT’s wish to move beyond the surface of his elaborate creation. By their desire, the Elves might be thought selfish, but Tolkien reveals for us the price for such behavior: “they were overburdened with sadness and nostalgic regret.” By attempting to preserve the past, and yet seeing that it couldn’t be preserved, the Elves had created not a pleasaunce, but a mirror of the passing of time which, powerful as they were, they could never control, and, gazing into that mirror, they could only see that truth, leaving them with nothing more than to feel sadness and regret.

The melancholy of the Elves is always there, but, in this particular letter, Tolkien explains and therefore deepens that haunting feeling, giving us figures who, in some sense, have tried to do the impossible: to stop time, and, realizing that they can’t, can only grieve—and retreat from the world of their failure.

I’ll always read letters for the living voice I might find there (the ancient Roman Seneca, c.4BC-65AD, first became real for me from one of his letters), but this one underlines my other point: reading letters—rereading letters—may bring surprises.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

Beware of staring too long into mirrors (think of Snow White’s stepmother),

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O