Tags

anachronisms, bacon and eggs, Billina, Chickens, Claymation, Nomes, Oz, Ozma, The Hobbit, Winky Guards

Welcome, dear readers, as always.

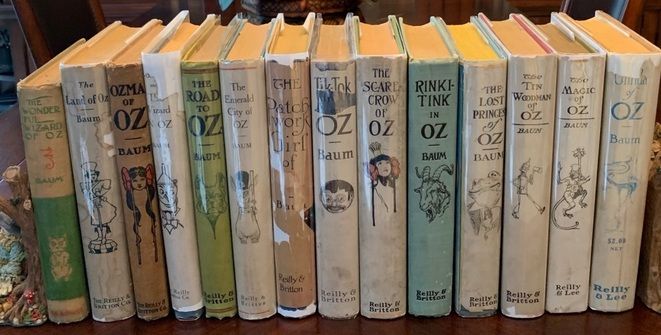

Recently, I had an interesting conversation with a dear friend on the subject of Oz books. As a child, he had read all of them, whereas I used to look at the whole shelf of them in the local library

and puzzle over names like “Tik-Tok” and “Rinky-Tink”, with their strange covers,

but, interested in history and science fiction, I never read one of them, going to other sections of the library for my books. My only contact with Oz lay in the (then) yearly showing of “The Wizard of Oz” on TV, where I would be yearly creeped out by what I later found out were the Winky Guards and their song—

which you can see/hear here, in case you’ve forgotten the Winkies: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nx8-J66yawM

Then came a kind of sequel, “The Return to Oz”,

with its wonderful Claymation figures

and its critics: it had run together a number of different Oz books, taking something from here and there, as well as adding what might be a disturbing element about the early use of shock treatment (Dorothy’s Aunt Em has Uncle Henry take her to an early clinic where her stories of her adventures in Oz are to be—literally—shocked out of her. Anyone who has read Silvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, 1963, will know what a horrific form of treatment this is.)

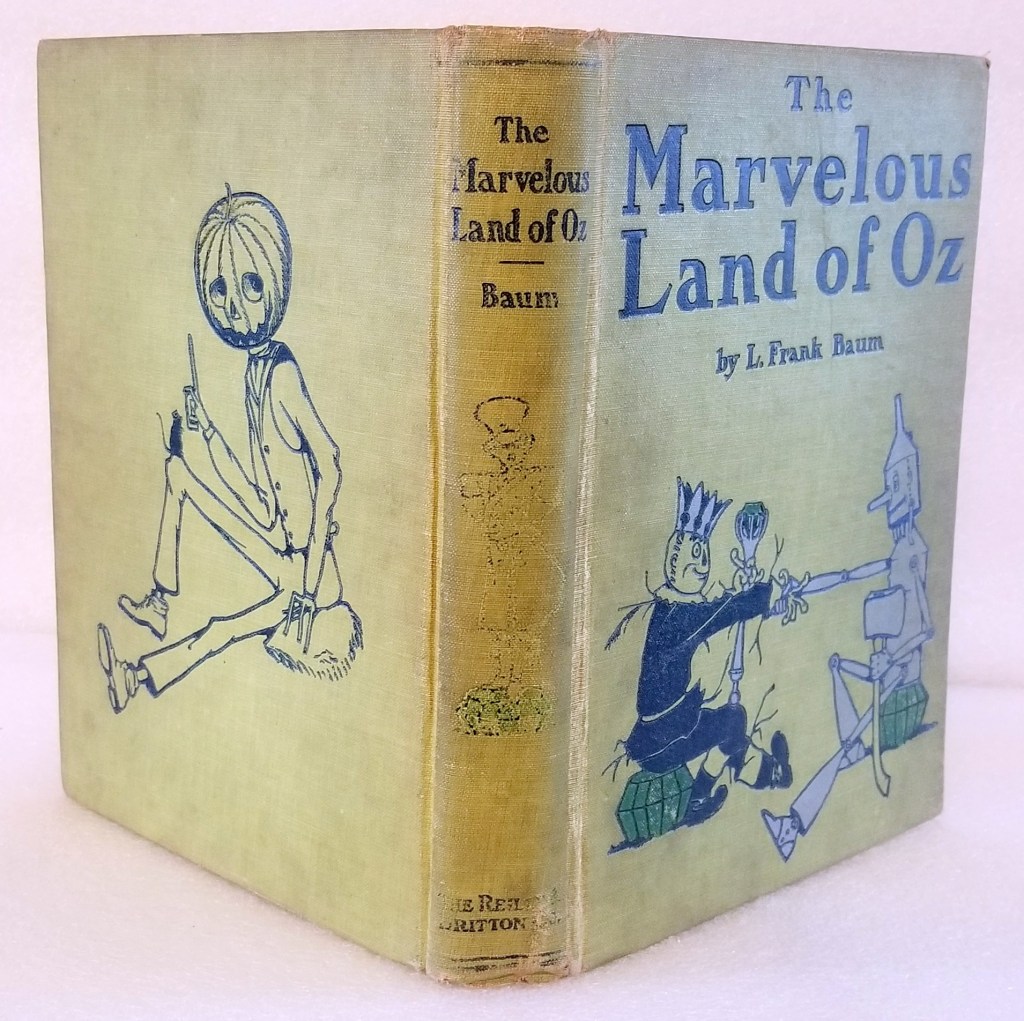

As someone innocent of Oz, I had no idea if any of this criticism were true—although I was sure that L. Frank would never have sent Dorothy to such a place—but much later, doing research for an earlier posting, I saw that the script writers had combined two figures the witch Mombi, from The Marvelous Land of Oz, 1904

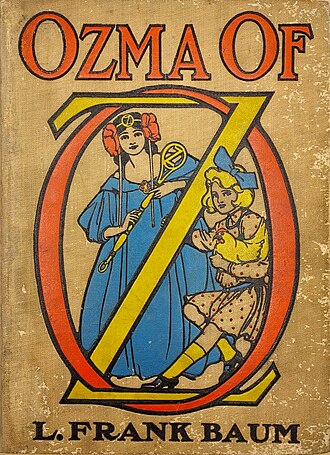

with Princess Langwidere, from Ozma of Oz, 1907,

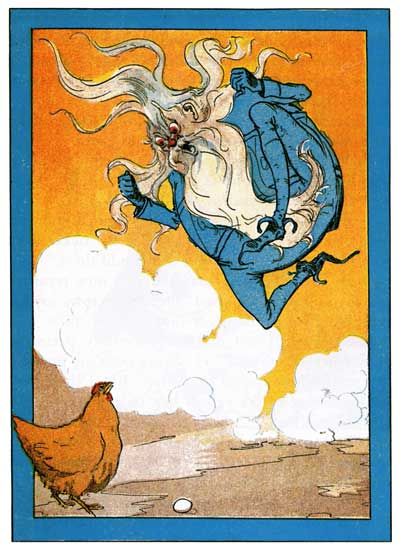

making her the “Princess” Mombi and giving her the actual Princess’ collection of heads (she liked to change them, depending upon her mood). Also from Ozma, along with other characters and details, came the Nomes, led by their king, Dorothy, and Dorothy’s pet chicken, Billina, who, in the world of Oz, could talk.

This last character would actually be crucial in the film as in the book, as the Nomes had a definite weakness:

“But—thunderation! Don’t you know that eggs are poison?” roared the King, while his rock-colored eyes stuck out in great terror. «Poison! well, I declare,” said Billina, indignantly. «I’ll have you know all my eggs are warranted strictly fresh and up to date. Poison, indeed!” «You don’t understand,” retorted the little monarch, nervously. “Eggs belong only to the outside world—to the world on the earth’s surface, where you came from. Here, in my underground kingdom, they are rank poison, as I said, and we Nomes can’t bear them around.” (Ozma of Oz, Chapter XV, “Billina Frightens the Nome King”)

In the film, it’s one of Billina’s eggs which destroys the Nome king, but, in the book, they are more of a provocation and the Nome king is defeated—but not killed—when his magic belt (which Billina has heard mentioned earlier) is pulled from him.

Dorothy and Billina are, of course—and proudly—from Kansas but, as I’m always interested in backstories and origins, I wondered: before Kansas, where did chickens come from originally? Are chickens indigenous?

But, as chickens turn out to be ancient, the answer is “it’s complicated”.

Wikipedia begins:

“The chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) is a large and round short-winged bird, domesticated from the red junglefowl of Southeast Asia around 8,000 years ago.”

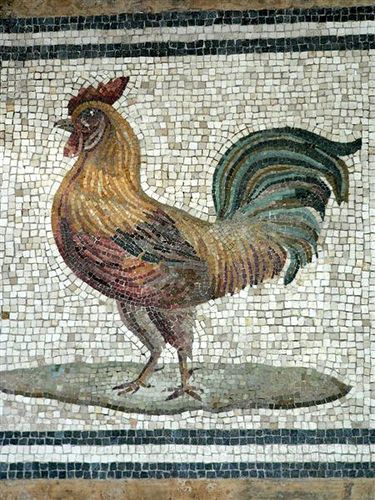

The first question which immediately springs to mind is: “Southeast Asia? Around 8,000 years ago?” And how did this domesticated creature come west—and when? Lots of mystery here, with explanations like “it came via Persia”, which is a pretty long distance from Southeast Asia. Ancient Greece, clearly had them, but, although it has a word for “rooster” (“alektor”, among related forms, transliterated) and provides us with lots of illustrations of them,

(5th century BC)

doesn’t appear to have a separate word for hens—without hens, however, no more roosters, so hens were obviously present. Ancient Rome has gallus for a rooster and gallina for a hen (along with pullus, which has a more generic meaning of “young one”—but is clearly the ancestor of “pullet” from Old French poulette, a diminutive of poule, “a hen”), but, when it comes to illustrations, images are seemingly almost entirely of roosters

and images of hens are as rare as—dare I say it?—hens’ teeth.

The Romans didn’t introduce chickens to the UK—recent archeological evidence suggests the pre-Roman 5th-3rd century BC—but we can presume that the chickens found a home there and, from there, traveled to the New World in the Age of Colonization, eventually making their way to Kansas, where some gallinaceous ancestors produced Billina.

As we know, Tolkien became aware of anachronisms in the 1937 The Hobbit—

things like:

“…he began to feel a shriek coming up inside, and very soon it burst out like the whistle of an engine coming out of a tunnel”

and, in the 1966 revision of the text, he considered replacing them. Ultimately, references to tobacco remained, as did that engine, but one thing did change, Gandalf’s demand:

“And just bring out the cold chicken and tomatoes”

became “And just bring out the cold chicken and pickles!”

Gandalf just previously had requested, “Put on a few eggs, there’s a good fellow!”

showing an instance where the egg came before the chicken—always a philosophical problem as to precedence—but it’s clear that JRRT was quite convinced that, although tomatoes might be alien, chickens and their produce were native and that the Nome king’s view of eggs:

“Eggs belong only to the outside world—to the world on the earth’s surface, where you came from. Here, in my underground kingdom, they are rank poison, as I said, and we Nomes can’t bear them around.”

might pertain to Oz, but not to Middle-earth.

As always, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

Whichever came first, where would bacon be without eggs?

(Bilbo might be polled on this as, throughout The Hobbit, his thought of comfort always includes this dish)

And remember that there’s always

MTCIDC

O