Tags

This is camellia sinensis

and, without it, two literary moments might never have appeared: one zany (or weird, depending upon your taste for such things) scene, and one scene crucial to the whole fabric of the piece.

The genus is clearly very talented, producing, on the one hand, camellias, with their beautiful flowers, like this—

(this is by Clara Maria Pope and comes from Samuel Curtis’ A Monograph on the Genus Camellia, 1819)

and, on the other, this—

The history of drinking the latter stretches back farther in Chinese history than is probably ever datable (you can read about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea ), but we’ll join it when it arrives as a popular beverage in England. That early history begins, in fact, with coffee.

In 1652, the valet of an English Levant (Middle-Eastern) merchant, Pascua Rosee, opened what is thought to be the first coffee house in London. It was a success and soon coffee houses became popular hangouts for those with the time and money for the then-exotic drink.

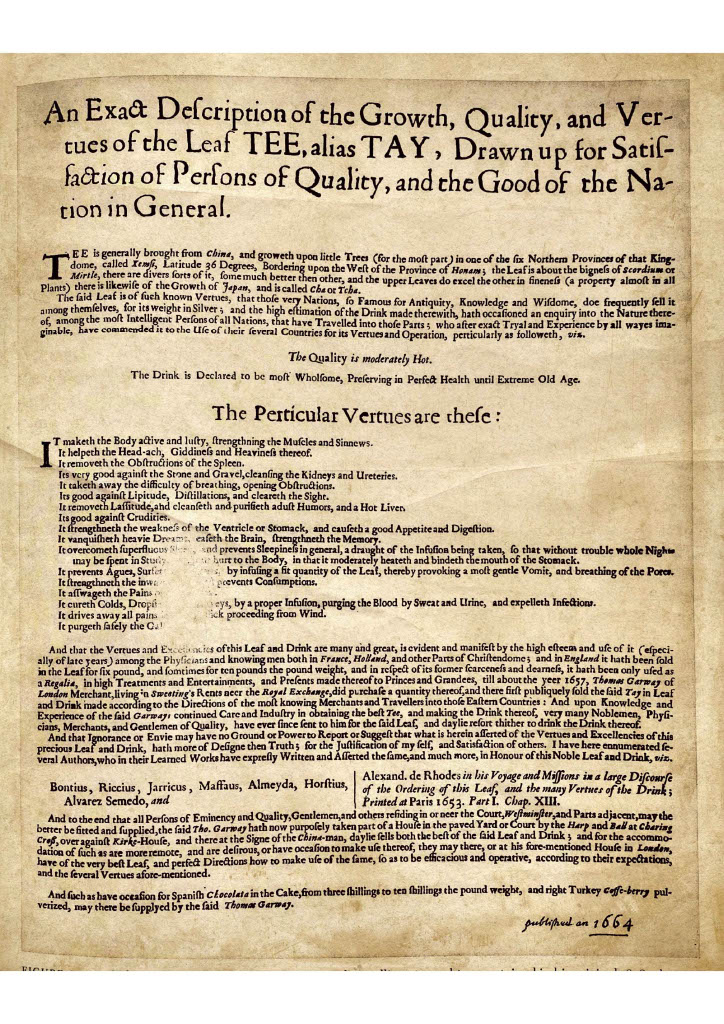

Rosee even advertized it as a kind of health-drink.

(Note the “scientific” tone of this handbill.)

In 1657, Thomas Garway (also spelled “Garraway”) began selling tea at his coffee house, later producing his own handbill on his new product.

How it spread from a London venue and eventually became a “national institution” is really about society and its influence, beginning with the wife of Charles II, Catherine of Branganza, 1638-1705,

who was already drinking tea, probably because the Portuguese had, from the early 16th century, been trading in China. As tea was initially expensive, it remained in the hands (and mouths) of the upper classes, in part because it was taxed, almost from its beginnings. As happened here in colonial America, this led to smuggling, but, in contrast to American violent protests,

this, in turn, led to pressure by British tea merchants upon Parliament and the tax was lowered and lowered and, in time, tea became a common (non-alcoholic) drink, even becoming part of the Temperance (anti-alcohol) Movement. (for a good survey of all this, see: http://www.tea.co.uk/page.php?id=98 )

As for “tea” as a kind of meal, there is a rather comic story of its invention by Anna Maria Russell, the 7th Duchess of Bedford, which you can read here: https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/tea-rific-history-victorian-afternoon-tea She claimed to have created afternoon tea about 1840, but, in fact, “tea” as a meal stretches back into the 18th century, as you can read here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tea_(meal) Afternoon tea, as practiced by the wealthier classes, could be quite a spread, as you’ll read,

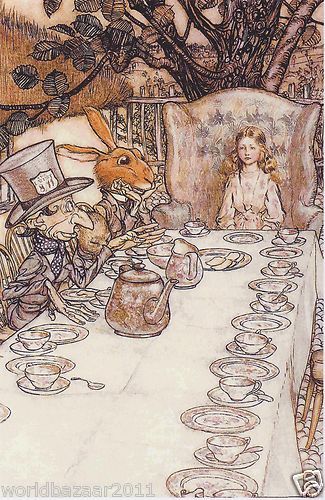

but it could also be simply a sort of late afternoon break, about 4, and I wonder if that must be the time of our first literary moment.

(Arthur Rackham)

“THERE was a table set out under a tree in front of the house, and the March Hare and the Hatter were having tea at it: a Dormouse was sitting between them, fast asleep, and the other two were using it as a cushion resting their elbows on it, and talking over its head. ‘Very uncomfortable for the Dormouse,’ thought Alice; ‘only as it’s asleep, I suppose it doesn’t mind.’ “ (Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Chapter VII, “A Mad Tea-Party”)

(A dormouse is a kind of mouse, as the name suggests, but I suspect that Carroll, with his keen ear for language, was also hearing “dormeuse”—French for a feminine “sleeper”)

The oddness of it is that, with a long, set table, there are only three participants, until Alice arrives and the Hatter and Hare then both shout “No room! No room!”

“Mad as a hatter” and “mad as a March hare” are old expressions for being less-than-sane, but there is an odd sane answer for the long, set table. It seems that, for a rather complex reason, local time has stopped, as the Hatter explains, adding:

“‘It’s always six o’clock now.’

A bright idea came into Alice’s head. ‘Is that the reason so many tea-things are put out here?’ she asked.

‘Yes, that’s it,’ said the Hatter with a sigh: ‘it’s always tea-time, and we’ve no time to wash the things between whiles.’

‘Then you keep moving round, I suppose?’ said Alice.

‘Exactly so,’ said the Hatter: ‘as the things get used up.’

‘But what happens when you come to the beginning again?’ Alice ventured to ask.”

But, like so many questions in Wonderland, this is never answered.

Afternoon tea is, customarily, at 4pm, suggesting that, in fact, the Hatter and Hare really don’t dirty the dishes because, if it’s always 6pm, tea is long over and therefore they may never actually have it, which is a very Carrollian way of thinking. (Alice, however, helps herself to tea and bread and butter, but perhaps this is because, of the three (or four, counting the dormouse), she is the only sane—and perhaps real?—one.)

Our second literary moment begins with an actual invitation to tea—after all, Alice simply sat down, which the March Hare suggests was very rude. But was it really meant?

“ ‘Sorry! I don’t want any adventures, thank you. Not today. Good morning! But please come to tea-any time you like! Why not come tomorrow? Come tomorrow! Good bye!’

With that the hobbit turned and scuttled inside his round green door, and shut it as quickly as he dared, not to seem rude.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 1, “An Unexpected Party”)

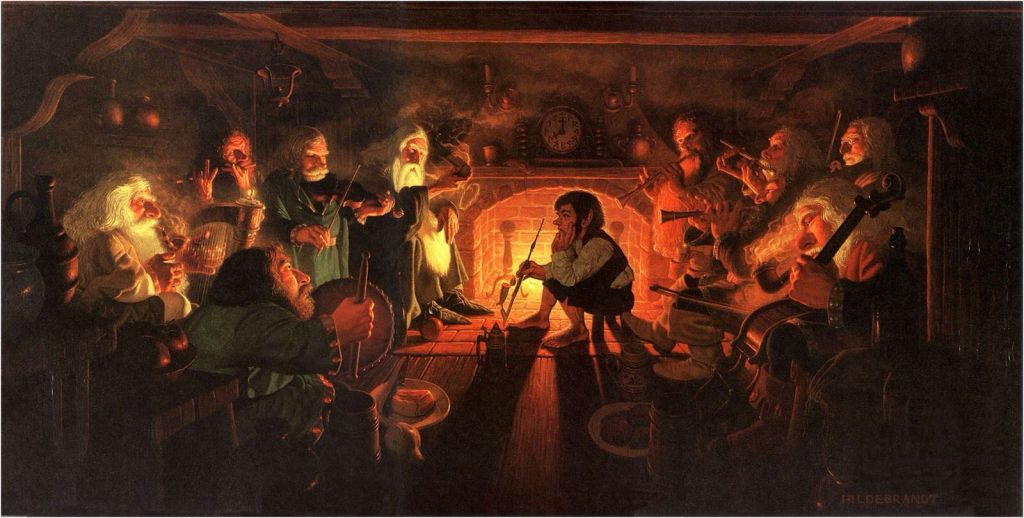

(the Hildebrandts)

We know what happens next, of course: the next day, not only Gandalf, but a whole troop of dwarves arrive and the quiet tea for two quickly becomes a boisterous—not afternoon tea (as we know from Chapter 18 that Bilbo sees tea as the traditional 4pm and serves cake)–but what’s called “high tea” or “meat tea” , and which, in older days, might have been dinner for working class people.

(the Hildebrandts again)

Meat tea, as its name suggests, is more than bread and butter or cake (you can read about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tea_(meal)#High_tea )—and that’s exactly what the dwarves—and Gandalf– demand, from “mince-pies and cheese” to “cold chicken and pickles”, but, interestingly, tea itself quickly disappears as coffee, red wine, and ale are called for, so what began as a simple invitation—and one meant to avoid adventure—itself becomes a culinary adventure, but, for that tea originally offered, would there ever have been any adventure at all?

And, remembering where tea came from in our Middle-earth, where do you suppose Bilbo’s may have come from?

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

Enjoy this pixilated version of the tea party from Disney’s Alice , 1951: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5KDwE6MjfmQ (warning: if you’re a purist, this will not be—dare I say it?—your cup of tea)

And remember that there’s always

MTCIDC

O