As ever, dear readers, welcome.

As I reread The Hobbit for the fall semester, I came across this-

“Far, far away to the West, where things were blue and faint, Bilbo knew there lay his own country of safe and comfortable things…

‘The summer is getting on down below,’ thought Bilbo, ‘and haymaking is going on and picnics. They will be harvesting and blackberrying, before we even begin to go down the other side at this rate.’ “ (The Hobbit, Chapter 4, “Over Hill and Under Hill”)

Gandalf, the dwarves, and the hobbit are beginning their trip through the Misty Mountains, an increasingly bleak place

(JRRT’s sketch, but from the far side of the Mountains)

which, although they don’t know it yet, will lead the group to goblins

(This is by Justin Gerard and you can see more of his striking work here: https://www.gallerygerard.com/the-art-of-justin-gerard )

and Bilbo to “Riddles in the Dark”,

(Alan Lee)

so it’s easy to understand why Bilbo is thinking of pleasanter things (being safe in bed and eating bacon and eggs are also daydreaming possibilities for him). But what about haymaking? A common older proverb in English is “Make hay while the sun shines”, meaning “do something when you can best accomplish it”, but how do you “make hay”?

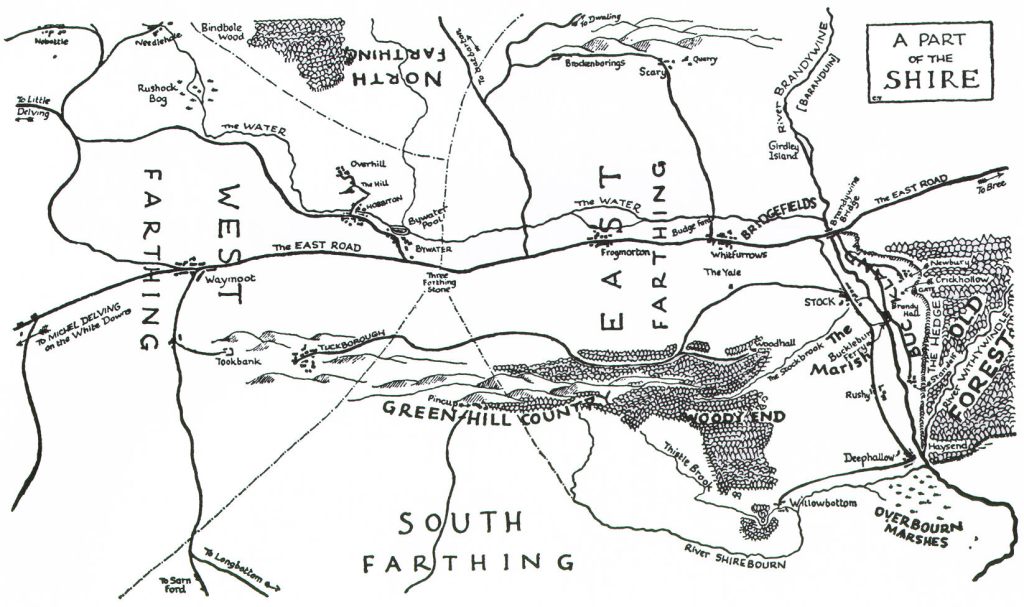

From Tolkien’s map of the Shire

and from hints here and there, principally in The Lord of the Rings, it’s clear that much of it is an agricultural landscape (as Tolkien writes to Naomi Mitchison: “The Shire is placed in a water and mountain situation and a distance from the sea and a latitude what would give it a natural fertility, quite apart from the stated fact that it was a well-tended region when they took it over…” (letter to Naomi Mitchison, 25 September, 1954, Letters, 292)

We know that the South Farthing, for example, has tobacco (“smoke leaf”) plantations,

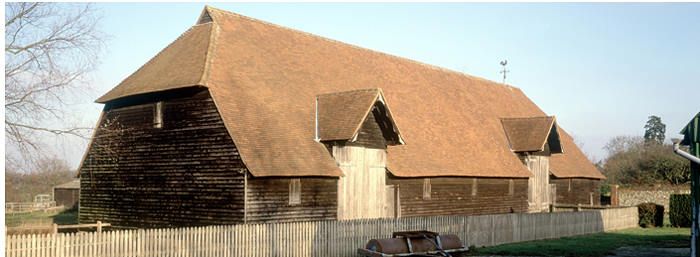

(although this is an all-too-modern barn—I imagine that hobbit barns would be more medieval-looking

like Prior’s Hall Barn here, built in the mid-15th century.)

Farmer Maggot, in the East Farthing, grows turnips,

and, as it’s probable that he brews his own beer, he’ll be growing barley

and, for flavoring, may grow hops.

(Those odd-looking buildings in the background are oast houses, where the hops are dried before use.)

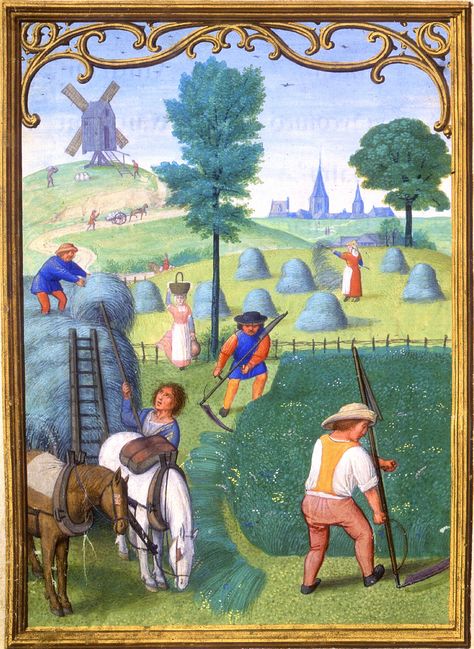

Hay can be made from any number of plant products and come from fields devoted entirely to the hay-making process, but Farmer Maggot may also set aside some of his barley-fields, which will be cut before quite ripe, to keep as much of the nutrition for cattle-feed in the hay.

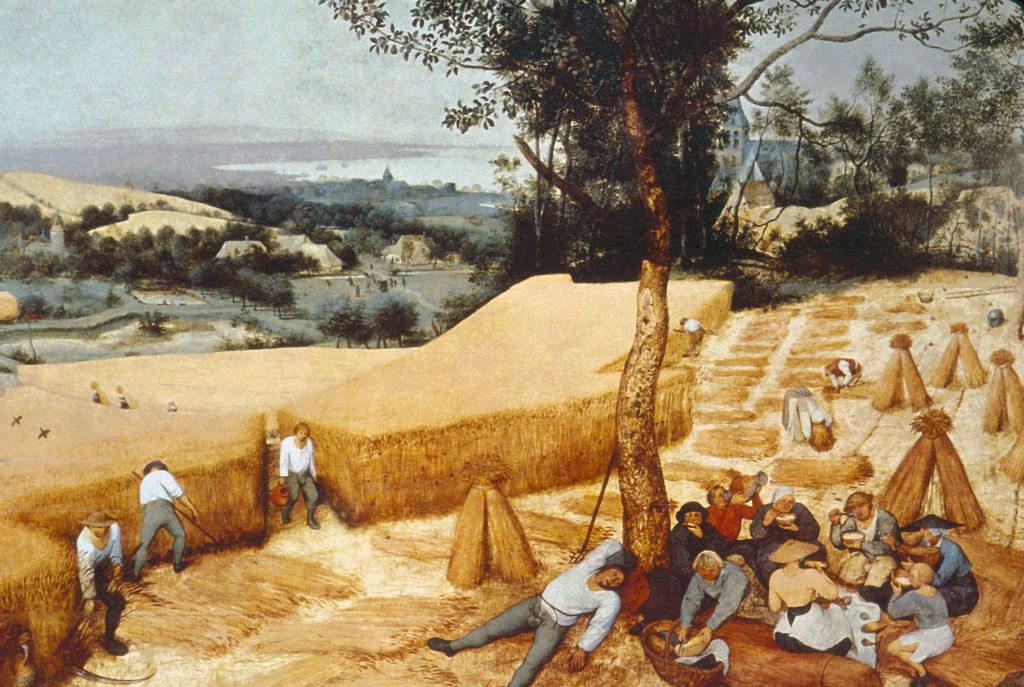

This can be a tricky operation as, to preserve the goodness of the hay, it needs to be spread out and dried in the sun before it’s collected (a process called “tedding”). Sudden wet weather can ruin a crop by dampening it to the point that there will be too much moisture, which can cause rot or encourage disease. (For a very practical 16th-century description of this process, see pages 33-34 of Sir Anthony Fitzherbert’s The Book of Husbandry, 1534, edited by Walter Skeat for the English Dialect Society in 1881, at: https://archive.org/details/bookofhusbandry00fitzuoft/page/32/mode/2up ) Once the hay is dried on both sides, it’s forked into haycocks (you can see them in the background of the previous image—Fitzherbert recommends doing this twice, gathering the hay into larger cocks the second time–from which it can be loaded onto carts and taken to be stored in a barn–also depicted in this image).

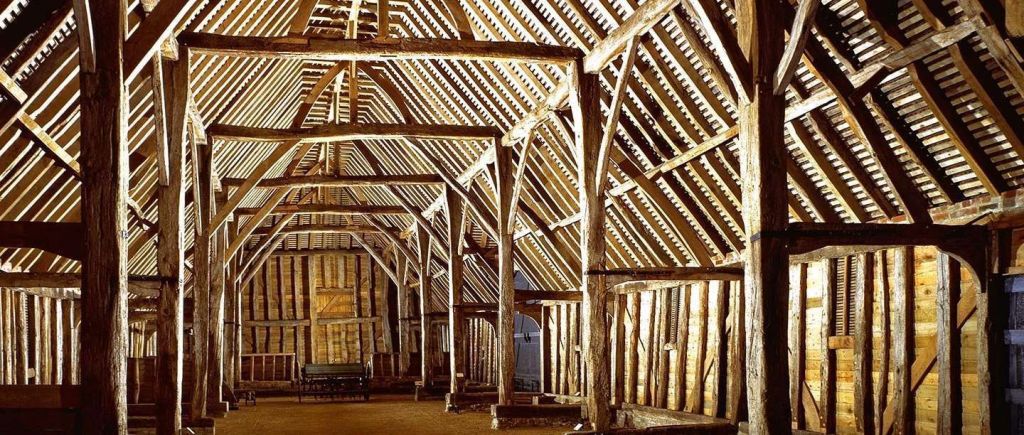

(This is the beautifully-reconstructed interior of the Prior’s Hall Barn.)

What Bilbo thinks he’s missing, then, is the (hopefully) sunny days when hay is mown (late June, early July in the UK) and tedded (not that he, who is a wealthy gentleman, would ever be doing any of that manual labor.) But what about picnics?

As is the case with many words in English, there is a scholarly tussle over just when and where this word first appears–probably the 18th century–but I’ll leave it to this article to say more about the word and its usage: https://www.historytoday.com/archive/historians-cookbook/history-picnic

and, instead, wonder who was doing the picnicking and where? Is Bilbo actually thinking about a genteel outdoor meal, like this 19th-century painting of an 18th century festivity?

or something more rustic, like this 16th-century image of workers taking time off from the field?

In any event, just as in his longing for the comfort of eggs and bacon, his inclusion of picnics with haymaking

reminds us of a strong trait of hobbits—

“Their faces were as a rule good-natured rather than beautiful…with mouths apt to laughter, and to eating and drinking. And laugh they did, and eat, and drink, often and heartily, being fond of simple jests at all times, and of six meals a day (when they could get them).” (The Lord of the Rings, Prologue, I, Concerning Hobbits)

No wonder a dream of far-off comfort includes eating.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

Hope for three sunny days in hay-making time,

And remember that there’s always

MTCIDC

O

PS

In case, after haymaking and picnicking, you feel inclined to join the fiddler,

(Cornelis Dusart, 1660-1704)

here’s a 17th-century dance with an appropriate title (and directions on how to do it)—

And here’s a transcription into modern notation, if that earlier form is a bit puzzling: https://playforddances.com/dances-2-3/hay-cock-a-hay-cock/

PPS

And I can’t resist adding what seems like an appropriate poem by Robert Frost (1874-1963)

Mowing

There was never a sound beside the wood but one,

And that was my long scythe whispering to the ground.

What was it it whispered? I knew not well myself;

Perhaps it was something about the heat of the sun,

Something, perhaps, about the lack of sound—

And that was why it whispered and did not speak.

It was no dream of the gift of idle hours,

Or easy gold at the hand of fay or elf:

Anything more than the truth would have seemed too weak

To the earnest love that laid the swale in rows,

Not without feeble-pointed spikes of flowers

(Pale orchises), and scared a bright green snake.

The fact is the sweetest dream that labor knows.

My long scythe whispered and left the hay to make.

This comes from Frost’s 1915 collection A Boy’s Will and you can read the whole collection here: https://archive.org/details/boyswill00fros/mode/2up A couple of vocabulary words–forgive me if these are already known to you—

Scythe

which you probably know from images of “the Grim Reaper”, who cuts down everyone the way a harvester cuts down all the grain—

Swale

This is defined as a “valley or low place” in a Webster’s An American Dictionary of the English Language from 1865—you can read that definition here: https://archive.org/details/americandictiona00websuoft/page/1336/mode/2up

As I’m sure that you have seen plenty of those, I include this Eastman Johnson (1824-1906) of a harvester sharpening his scythe.

Orchis

This is somewhat puzzling, as the Orchis is a genus in the Orchid family which doesn’t appear to be native to North America. I’m presuming that Frost is employing an earlier or perhaps American form of “orchid” ( in that same Webster’s An American Dictionary of the English Language from 1865, you can see that use: https://archive.org/details/americandictiona00websuoft/page/918/mode/2up )of which there are a good number of types available in North America. Using Frost’s clues—“feeble pointed spikes” and “pale”, as clues, I’ve included the image of a “White Fringed Bog Orchid” (Platanthera Blephariglottis) as a guess.