As always, welcome, dear readers.

“Still round the corner there may wait

A new road or a secret gate…”

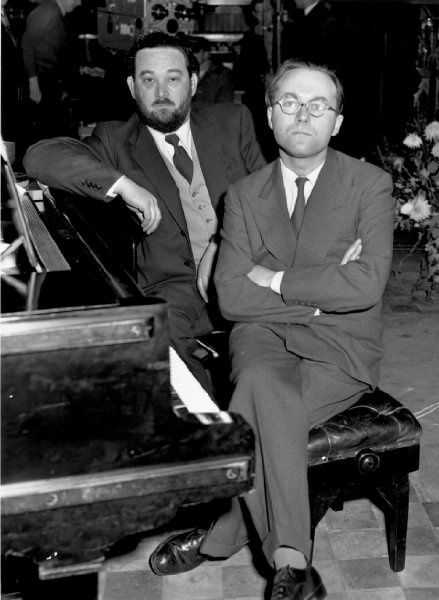

as Frodo and the other hobbits sing, “Bilbo Baggins [having] made the words, to a tune that was as old as the hills” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 3, “Three is Company”), and now that I’m about to teach The Hobbit again, I’ve noticed not anything so grand as a new road, but perhaps a new little footpath into the book. (For a modern setting of this song, of which JRRT approved, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YtH6ROfV7WA&t=75s This is from a cycle of Tolkien’s poems set to music by Donald Swann (1923-1994), who, along with Michael Flanders, was mentioned in my last posting.)

In my last, I was talking about fears—of spiders

and snakes

(and you’ll notice that I haven’t gone on to “and bears, oh my!” although the rhythm is hard to resist.)

but, rereading The Hobbit, where those spiders—and the big cousin of snakes, a dragon–

(JRRT)

appear, I’d been wondering what is it about these creatures which is most threatening? We might imagine the odd look of spiders, both the compound eyes and those rapidly-moving legs, and, for me, the wriggly motion of snakes (I’ve always thought that you can see, from muscular tension, what an attacking mammal might signal with its legs, but what do you do with something which has no legs?),

but here, I would propose, is a different possibility, consistent with all of the major threats in the book, and which lies in the title of this posting.

This title is, on the surface, just a kind of shorthand French for “May you enjoy your meal”, which I associate with a tv cooking show from long ago—

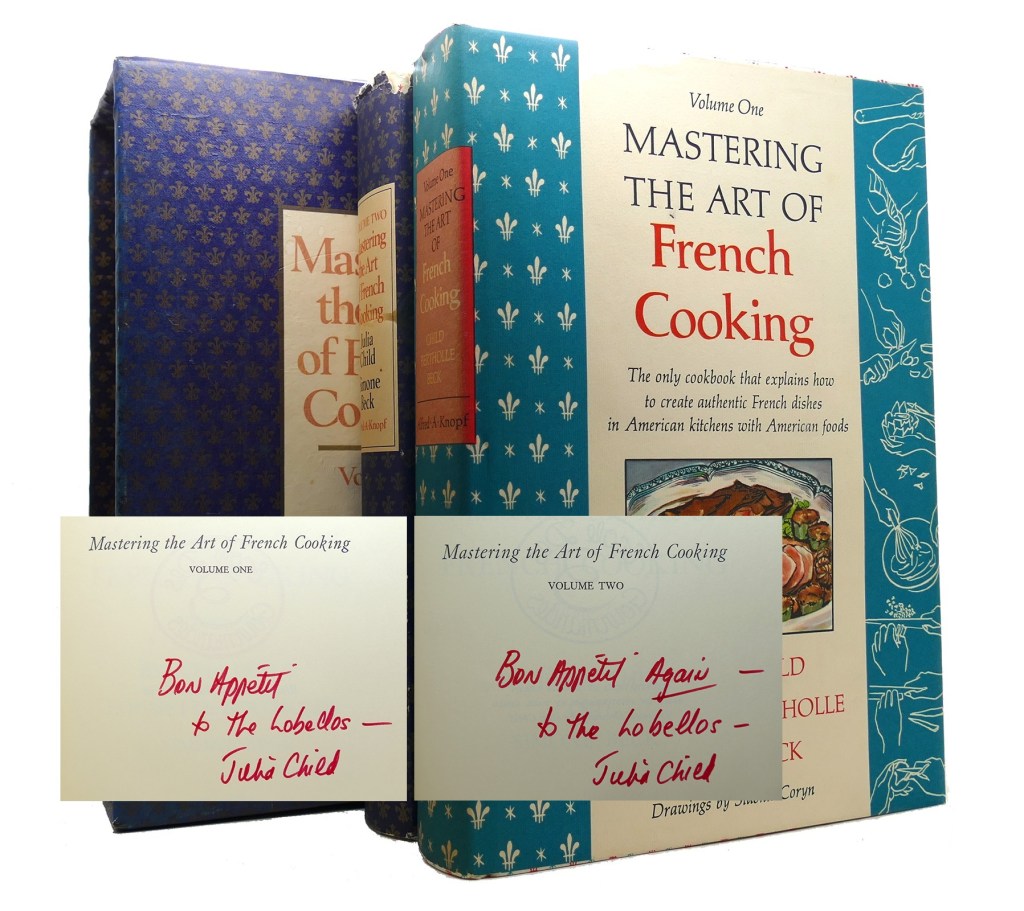

hosted by a very knowledgeable and enthusiastic Julia Child (1912-2004),

who ended every show by wishing her viewers, “Bon appétit!”

This show, as the title suggests, is all about French cuisine and the sometimes incredibly complex creation of it. (I myself own the first volume of Child and her collaborators’ Mastering the Art of French Cooking

but the only thing I’ve ever been able to make from it was quiche, as virtually everything else in it would appear to take numerous hours, a fully-equipped professional kitchen, and the kind of passionate staff we see in Ratatouille.

I note here, by the way, that Tolkien himself had strong views on such: “I smoke a pipe, and like good plain food (unrefrigerated), but detest French cooking…” from a letter to Deborah Webster, 25 October, 1958, Letters, 411)

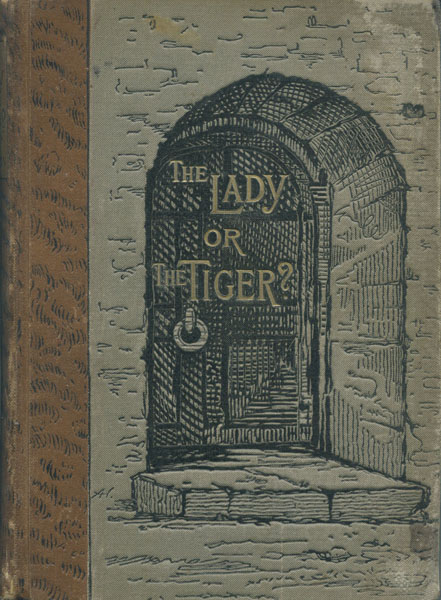

This title also leads to what I think is the real fear in most of The Hobbit, first introduced in Chapter 2—

“ ‘Mutton yesterday, mutton today, and blimey, if it don’t look like mutton again tomorrer,’ said one of the trolls…

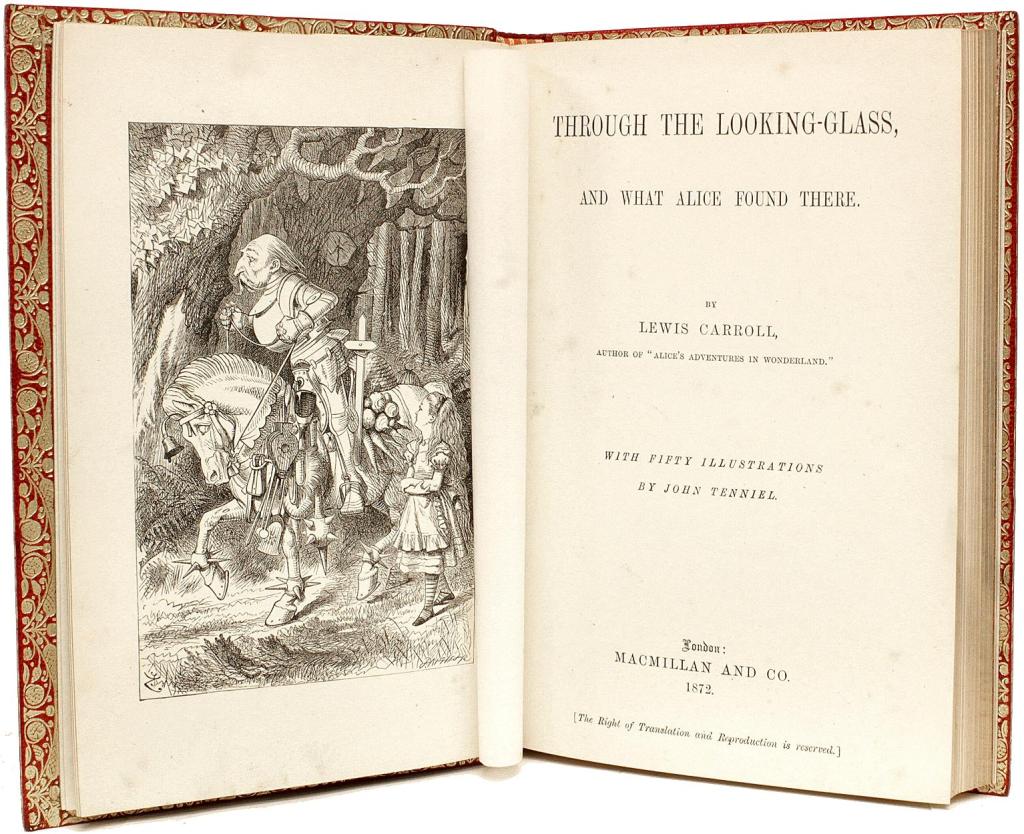

William choked. ‘Shut yer mouth!’ he said as soon as he could. ‘Yer can’t expect folk to stop here for ever just to be et by you and Bert. You’ve et a village and a half between yer, since we come down from the mountains. How much more d’yer want?’ “ (Chapter Two, “Roast Mutton”—we might also note a near-quotation from a book with which Tolkien was familiar, Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There, 1871—although the title page of the first edition says 1872–

where, in Chapter Five, “Wool and Water”, the White Queen explains to Alice something about Looking-Glass Land: “The rule is, jam to-morrow and jam yesterday—but never jam to-day.” You can read this on page 81 of the 1896 Ward Lock edition here: https://archive.org/details/ThroughTheLookingGlass/page/n77/mode/2up For Tolkien’s familiarity with Carroll’s works, see his letter to C.A. Furth, 31 August, 1937, Letters, 24-26.)

And this is only the first mention of such a danger—there’s:

“I am afraid that was the last they ever saw of those excellent little ponies…For goblins eat horses and ponies (and other much more dreadful things), and they are always hungry.” (Chapter 4, “Over Hill and Under Hill”)

and

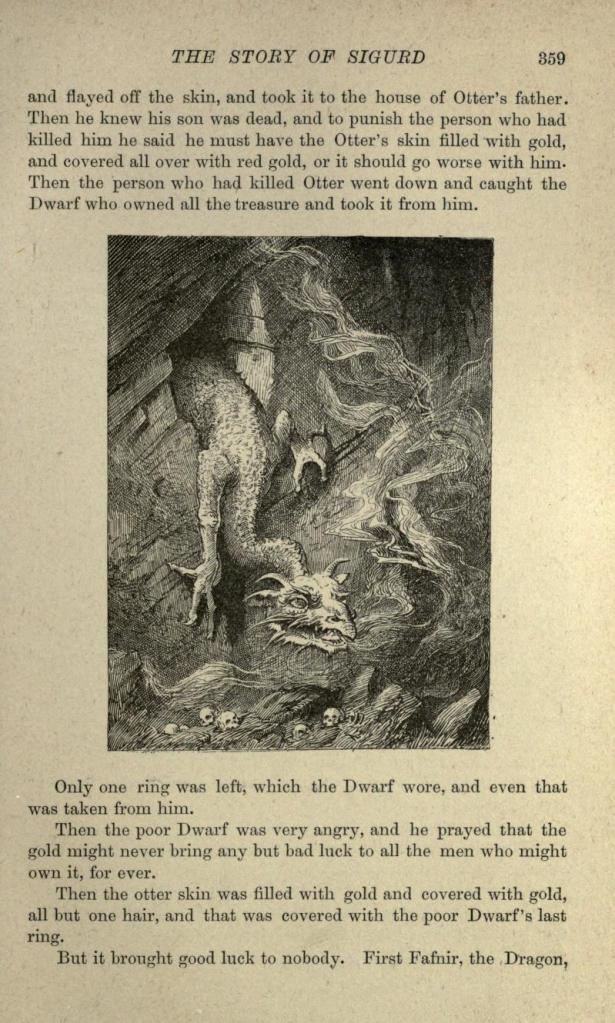

“[Gollum] liked meat too. Goblin he thought good, when he could get it…

“ ‘Does it guess easy? It must have a competition with us, my preciouss! If precious asks, and it doesn’t answer, we eats it, my preciousss.’ ” (Chapter 5, “Riddles in the Dark”)

and

“ ‘You’ve left the burglar behind again!’ said Nori to Dori looking down…

‘He’ll be eaten if we don’t do something,’ said Thorin…” (Chapter 6, “Out of the Frying-Pan Into the Fire”)

and

“ ‘It was a sharp struggle, but worth it,’ said one. ‘What nasty thick skins they have to be sure, but I’ll wager there is good juice inside.’

‘Aye, they’ll make fine eating, when they’ve hung a bit,’ said another. “ (Chapter 8, “Flies and Spiders”)

and, finally

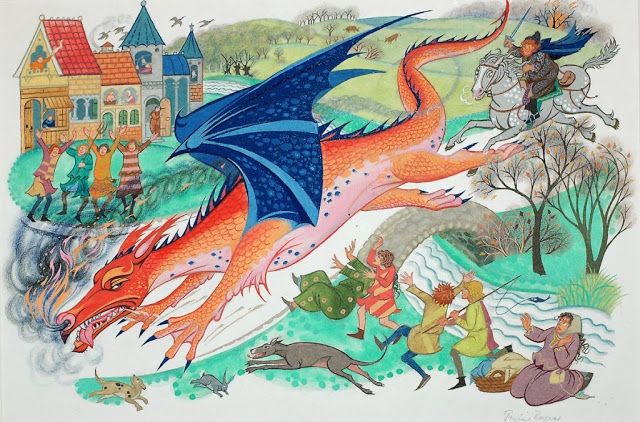

“ ‘Very well, O Barrel-rider!’ he said aloud. ‘Maybe Barrel was your pony’s name; and maybe not, though it was fat enough…Let me tell you I ate six ponies last night and I shall catch and eat all the others before long. In return for the excellent meal I will give you one piece of advice for your good: don’t have more to do with dwarves than you can help.’

‘Dwarves!’ said Bilbo in pretended surprise.

‘Don’t talk to me!’ said Smaug. ‘I know the smell (and taste) of dwarf—no one better.’ “ (Chapter 12, “Inside Information”)

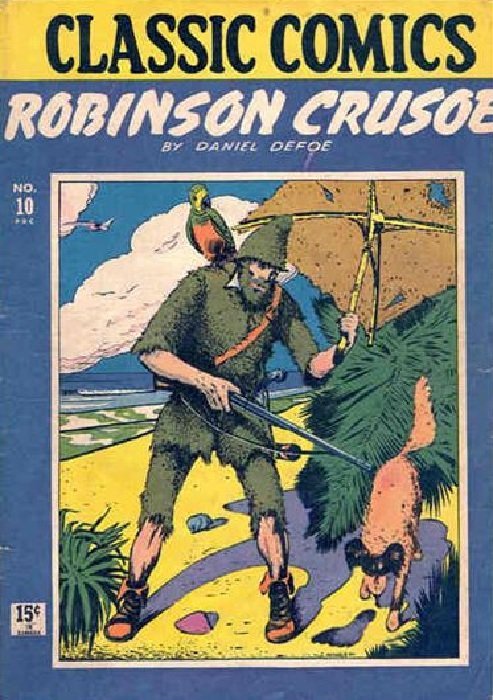

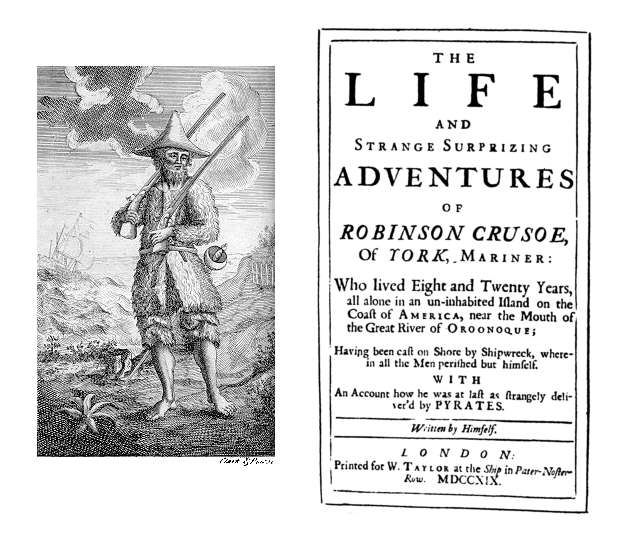

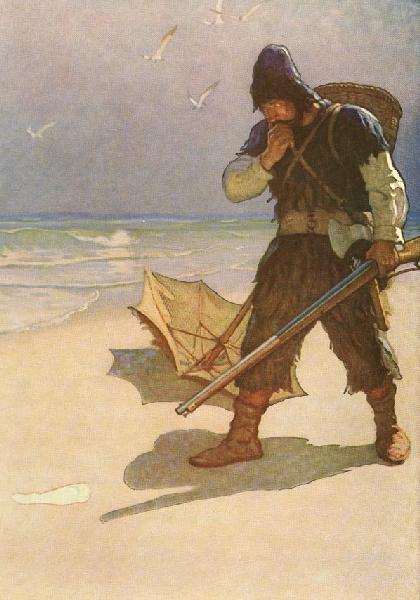

I think that I first met this danger when I was very small and read a comic book version of The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, 1719.

Crusoe had first been alarmed when, living on what he thought was a safely deserted island, he found a human footprint in the sand. Then, sometime later, he came upon something even more alarming:

“When I was come down the hill to the shore, as I said above, being the S.W. point of the island, I was perfectly confounded and amazed; nor is it possible for me to express the horror of my mind at seeing the shore spread with skulls, hands, feet, and other bones of human bodies; and particularly, I observed a place where there had been a fire made, and a circle dug in the earth, like a cockpit, where it is supposed the savage wretches had sat down to the inhuman feastings upon the bodies of their fellow-creatures.” (Robinson Crusoe, Chapter XVIII, page 217—you can read this in N.C. Wyeth’s splendidly-illustrated edition of 1920 here: https://archive.org/details/robinsoncrusoedefo/page/n249/mode/2up )

In other words, like Crusoe’s cannibals, it’s not the outside of trolls, goblins, wolves, spiders, and a dragon which we meet in The Hobbit and which produces the emotion the characters—and readers, too,–at least this reader—feel, but their plan to fill their insides with those characters: hence the cheerful but ultimately grim title of this posting.

Robinson Crusoe, in succeeding chapters, works his way through his fear and disgust, even, in a sense, trying to see cannibalism as custom of an alien culture (although killing a few cannibals later in the story), and, in The Hobbit, although the fear of being consumed is the major fear, no one is actually eaten, but it’s all left me wondering what recipes an anthropophagen version of Julia Child’s books might include… (and which might satisfy that bitter critic in Ratatouille, Anton Ego)

Thanks for reading, as always.

Stay well,

If you should see a footprint in the sand,

Head for the nearest exit in an orderly fashion,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

And here are Flanders and Swann

again with “The Reluctant Cannibal”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qjAHw2DEBgw