Welcome, dear readers, as always.

“cumque transissent quadraginta dies aperiens Noe fenestram arcae quam fecerat dimisit corvumqui egrediebatur et revertebatur donec siccarentur aquae super terram emisit quoque columbam post eum ut videret si iam cessassent aquae super faciem terraequae cum non invenisset ubi requiesceret pes eius reversa est ad eum in arcam aquae enim erant super universam terram extenditque manum et adprehensam intulit in arcamexpectatis autem ultra septem diebus aliis rursum dimisit columbam ex arcaat illa venit ad eum ad vesperam portans ramum olivae virentibus foliis in ore suo intellexit ergo Noe quod cessassent aquae super terramexpectavitque nihilominus septem alios dies et emisit columbam quae non est reversa ultra ad eum”

“And when forty days had passed, Noah, opening a window of the ark which he had made, sent out a raven, who was going out and returning while the waters were drying up over the earth. He sent out as well a dove after him so that he might see if now the waters had gone down [literally, “ceased”] over the surface of the earth who, when she had not found where she might rest her foot, returned into the ark to him (for the waters were still over the whole earth) and he stretched out [his] hand and brought the captured [bird] into the ark. However, when a further seven days had been waited out, he again sent out the dove from the ark, but it came to him at evening carrying in its mouth an olive branch with growing leaves and so Noah understood that the waters had receded over the earth and he waited no more than seven more days and sent out the dove which did not return again to him.”

(Genesis 8.6-12—my translation. The text is from Jerome’s translation, which you can read more of here, both in Latin and English, in Genesis 6-8: https://vulgate.org/ot/genesis_6.htm )

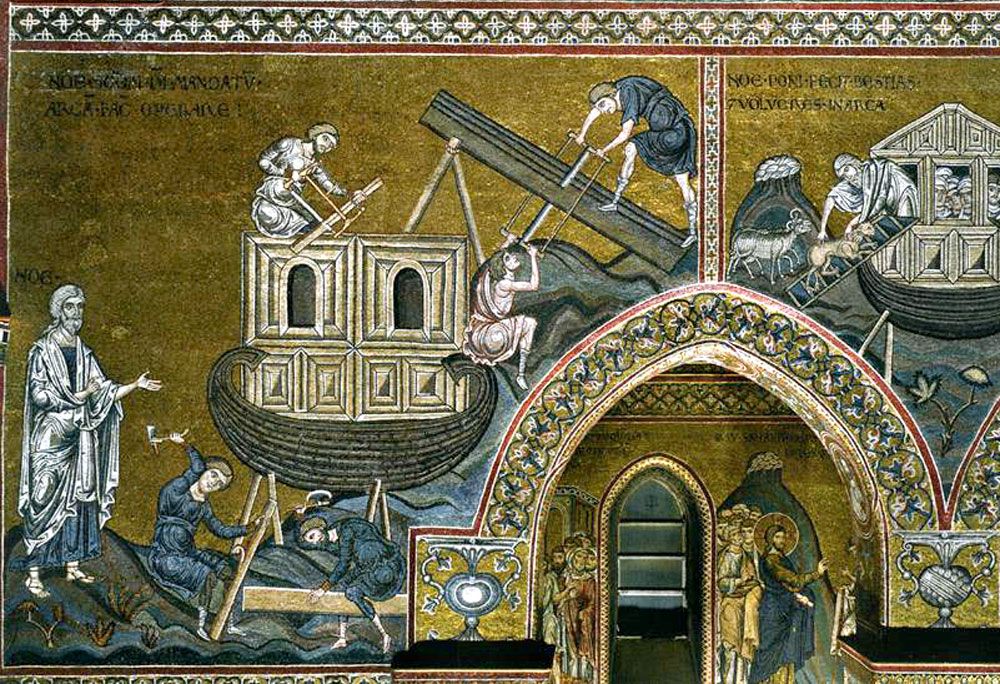

The story of the Flood stretches out, like its waters, over much of early Western human history, not only in the Judeo-Christian Bible, and in the story of Pyrrha and Deucalion in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (for more on Pyrrha, Deucalion, and floods, see “Flooded Out”, 6 April, 2022), but even in Tolkien, with the destruction of Numenor, but, for me, it’s both a wonderful story, and inspired some of my favorite medieval mosaics, those in the cathedral at Monreale, in Sicily.

Inside this amazingly colorful space, almost hallucinogenic, on one wall, are a series of images illustrating the story of Noah and his Ark.

I love the whole series (here it is: https://www.christianiconography.info/sicily/noahMonreale.html ), but, if I had to choose among them, it would be the building of the Ark

and the one which illustrates the title of this posting which I love most—

The construction of the building began in the reign of William II (1167-1189),

the Norman ruler of this part of Sicily. Here, he’s presenting the (in his time unfinished) structure to the Virgin Mary. Although, unfortunately, we don’t know the names of the artists who created such wonderful images, they presumably were either Byzantines or were trained in the Byzantine style of mosaic-making (for more see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monreale_Cathedral_mosaics ) and this makes another Tolkien connection for me, remembering his remark, in a letter to Milton Waldman, that

“In the south Gondor rises to a peak of power, almost reflecting Numenor, and then fades slowly to decayed Middle Age, a kind of proud, venerable, but increasingly impotent Byzantium.” (letter to Milton Waldman, “probably written in late 1951”, Letters, 203)

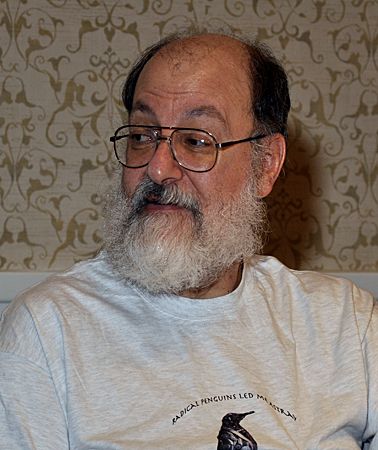

And “dove” and “Byzantium” bring me to the main subject of this posting, the science fiction/fantasy author, Harry Turtledove (1949-and may he live to be a 100 and more).

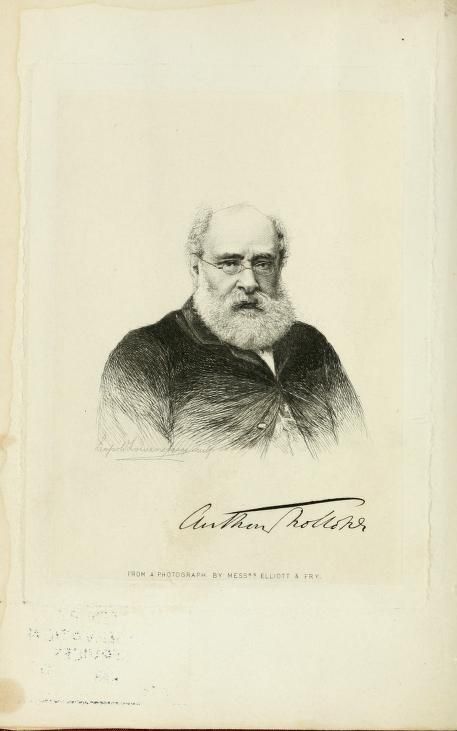

Turtledove, a lifelong Californian, got his PhD in Byzantine history from UCLA in 1977 with a dissertation entitled “The Immediate Successors of Justinian: A Study of the Persian Problem and of Continuity and Change in Internal Secular Affairs in the Later Roman Empire During the Reigns of Justin II and Tiberius II Constantine (AD 565–582) and this also fits into this posting—although Turtledove himself never fit into the academic world (too few jobs for Byzantinists, alas!) and, instead, became an astonishingly prolific author, with approximately 111 books by 2023 (not counting collaborations, short stories, edited collections and the fact that my eyes crossed after I counted 100—you can see a list in chronological order by series here: https://www.bookseriesinorder.com/harry-turtledove/ ). For a comparison, there’s Anthony Trollope (1815-1882),

a Victorian novelist known in his own time for his prolificacy, but who only turned out about 60 novels between 1847 and 1882. (For a list, see: https://www.orderofbooks.com/authors/anthony-trollope/ If you enjoy long, complex social novels written by someone with an eye for character and detail, and you don’t know his work, I would recommend starting with The Warden, 1855, which you can read here in an 1862 American reprint: https://archive.org/details/warden02trolgoog/page/n4/mode/2up )

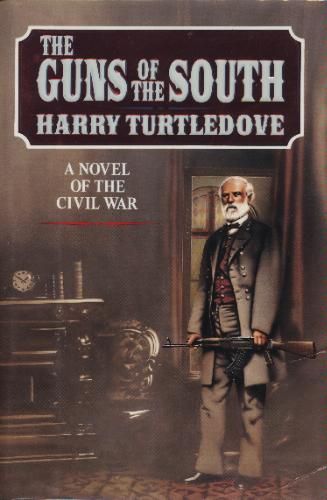

I had first met Turtledove’s work in a “what if” novel, The Guns of the South (1992),

in which time-travelers provide Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia with AK47s in 1863, with consequences which you might image for the Union Army of the Potomac and beyond. It was a good, gripping read and I was curious to see what else this man had written. My further connection with Turtledove was not “what if”, but fantasy–based upon the real Byzantium–and which began with a recommendation of his “Videssos” series by a friend who had once had seen him appear as a substitute for her regular professor in a class at UCLA. He lectured for over an hour without notes and, if she didn’t use the word “spell-binding”, she certainly gave me the impression that this was a born story-teller.

And so I came to “Videssos”, which is, in fact, Byzantium by another name, as the map which appears in the various series immediately indicates—

in which the world of the Mediterranean has been (roughly) reversed.

There are three series in all, plus one extra novel, The Bridge of the Separator (2005), a kind of “prequel” to the series published first (or perhaps to the whole series–I’m not quite clear on this), but which was not in the ultimate chronological structure of the whole.

The series first published (all in 1987) is that sometimes called “The Videssos Cycle”—

but which actually takes place at the end of the era which the total collection portrays. Next, moving backward, comes “The Time of Troubles”—

and finally comes the “Krispos” series.

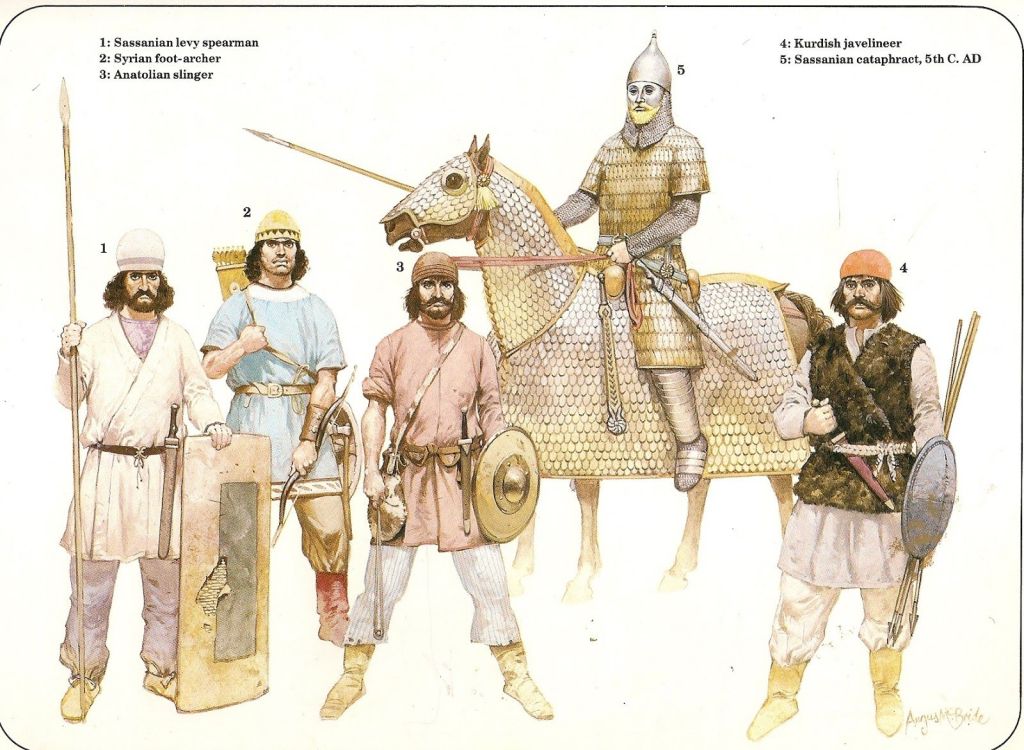

Unlike Turtledove, I’m not a Byzantinist, but it’s possible to recognize certain elements immediately. The “Makuraners”, for instance, appear to be based upon the fierce Sassanid Persians, with their heavily-armored cavalry,

(Angus McBride)

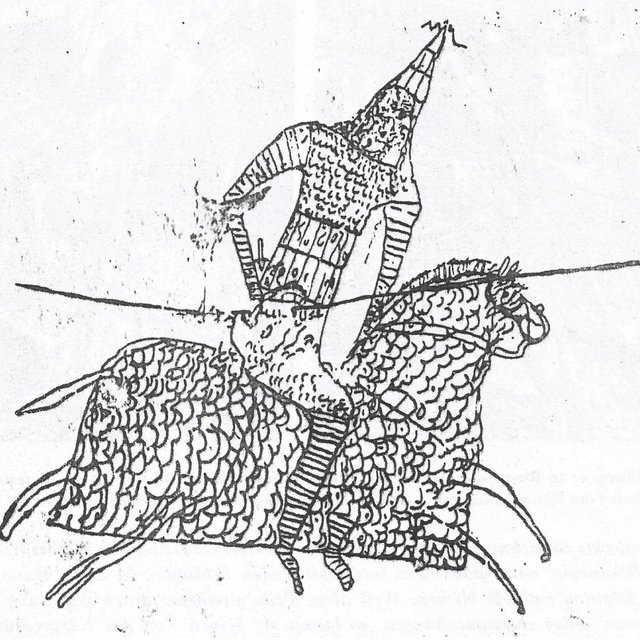

of which we actually have a period image from a sgraffito on a wall in Dura-Europos, which fell to the Sassanid king, Shapur I, in 257AD (Dura-Europos is a fascinating place in itself: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dura-Europos#Looting_by_ISIS )

The capital of Videssos, sometimes called “Videssos the City”, has a number of elements which make it an easy match for Byzantium at its height.

(For more parallels, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Videssos_cycle )

It’s not, however, the parallels which have interested me so much as the complexity of the world which these books provide. Like that of The Lord of the Rings, this is an ancient world, with a complicated history, ruled by dynasties which can be overthrown, all of it entangled with religion (much of it based upon ancient Zoroastrianism) and the most intelligent understanding—and depiction—of magic which I’ve read in fantasy novels. My friend’s depiction of Turtledove was clearly extremely accurate and, if you enjoy these, that’s only about a dozen books out of over a hundred. For years there’s been a game in which you’re asked, “If you could only take ________ with you to a desert island, what would you take?” Certainly, if I had to spend the (about) 370 days on the Ark with Noah, his family, and their vast collection of animals in 2s and 7s, I’d think seriously about answering, “How about the whole Turtledove opus?”

As ever, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

Try to remember just how long a cubit is,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O