Welcome, as always, dear readers.

In the world of things like this—

a question like this and its reply, seem completely normal:

“ ‘Where am I, and what is the time?’ he said aloud to the ceiling.

‘In the house of Elrond, and it is ten o’clock in the morning,’ said a voice. ‘It is the morning of October the twenty-fourth, if you want to know.’ “ (The Fellowship of the Rings, Book Two, Chapter 1, “Many Meetings”)

This is Middle-earth, however, late in the Third Age, and, although the responder can be certain of where he is and perhaps what the date is (after all, the narrator mentions, in the Prologue, that “Meriadoc…for his Reckoning of Years…discussed the relation of the calendars of the Shire and Bree to those of Rivendell, Gondor, and Rohan.” indicating that a good number of such must have been available), how does he know the time to the hour?

As discussed in a long-ago posting (“Peace! Count the Clock!” 25 October, 2017), Bilbo has a kind of wall clock at Bag End—

(That’s it, on the right hand wall—that thing to the left of the door is clearly a barometer, although it’s never mentioned in the text.)

and presumably that’s how he knows that tea is at 4 o’clock when he nervously invites Gandalf in his effort to avoid an ADVENTURE in Chapter 1 of The Hobbit.

(One of my favorites by the Hildebrandts)

There is no mention of a clock in Rivendell, however, which brings us back to the question of anachronisms, something which first pops up in relation to various lines in both the first and second versions of The Hobbit, with everything from tomatoes to steam engines, not to mention matches.

Suppose, however, that Gandalf hasn’t consulted an (unmentioned) wall clock, but something completely different, which descends from early clocks–

a pocket watch.

It’s also never mentioned, of course, but the Middle-earth of The Lord of the Rings is really a kind of late-medieval world and it’s in that world in our Middle-earth (which JRRT maintained is a direct descendant of his) that a Nueremberg clockmaker and inventor, Peter Henlein (1485-1545),

(As is the case with so many creative people of the more distant past, there is no known image of Henlein—this is a statue raised to him in Nueremberg in 1905.)

is credited, in his own time, with the invention of the pocket watch (see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Henlein although the copy of the work cited which I could obtain of Johannes Cochlaeus’ Cosmographia Pomponii Melae, 1512, which you can find here: https://archive.org/details/cosmographiapomp00mela/page/n3/mode/2up seems to lack the appendix in which Henlein is mentioned).

Here is an example—perhaps by Henlein himself.

This is made in the shape of a pomander—a container for an aromatic substance. In a world before mid-19th-century germ theory, people believed that miasma, “bad smell”, was the spreader of disease, and so carrying/wearing an object like this, stuffed with something sweet-smelling, would be (one hoped) a preventative. And, even if the air wasn’t plague-carrying, the streets and rivers around cities were often full of sewerage, so this might at least keep the nose from being overwhelmed by general environmental stinks. (You can read more about this here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pomander )

(A painting from the mid-1560s by Pieter Janz Pourbus, c.1523-1584)

You can see, then, how this could easily be converted into a watch case and carried the same way, suspended somehow from the body, as in the Pourbus portrait. Unlike a wall clock, with its pendulum and weights to keep it going, this early watch was based upon a wound-up spring, a mainspring, an ingenious idea in itself. (For more on pocket watches in general, see the very useful: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pocket_watch )

You can also imagine that this wasn’t something ordinary people owned, being made specifically for the well-to-do and even when they became more common, by Shakespeare’s time, they were still a status symbol, as Malvolio, the ambitious Puritan steward in Twelfth Night, 1601-2?,

(By Daniel Maclise, 1806-1870)

demonstrates, when he sees himself as married to his countess, Olivia. In his delusion (brought on by others, out to humble him for their own amusement), he fancies that he sends for the countess’ uncle, Sir Toby Belch (not one of Shakespeare’s subtler names)–

“Mal. Seauen of my people with an obedient start,

make out for him: I frowne the while, and perchance

winde vp my watch, or play with my [–] some rich Iewell:

Toby approaches; curtsies there to me.”

(Twelfth Night, Actus Secundus, Scaena Quinta. If you read this blog regularly, you know that I always try to use the earliest source for quotations and, with Elizabethan/Jacobean English, this means using a text from the Internet Shakespeare site, as its spelling is a good prompting as to Elizabethan pronunciation, which is the ancestor of our later speech, but definitely a much richer sound than at least Received (American) Standard. This is from the “First Quarto”, 1623, which you can find here: https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/TN_F1/index.html For more on Elizabethan pronunciation, see, for example: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WeW1eV7Oc5A This is from one of my favorite on-line language sites, NativLang. If you, like me, are fascinated by any and every language, this is a site you will very much enjoy.)

Now consider Gandalf’s voluminous robes—

If you could peer just inside, could you imagine that he had one of these

and, when Frodo asked the time, Gandalf reached in to consult it?

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

Remember what the thief of time is,

And remember, as well that there’s always

MTCIDC

O

PS

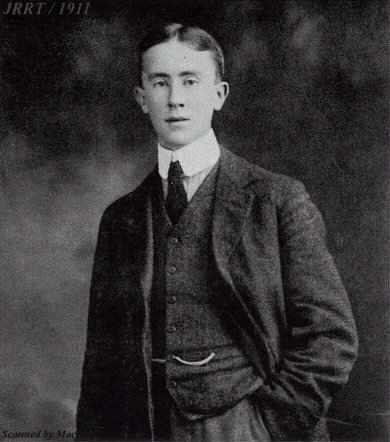

A cursory search through the various Tolkien portraits on-line never reveals a wrist watch, but numerous vests (and possibly trouser watch pockets, called “fobs”).

Could Tolkien have followed the pre-Great War men’s fashion (changed for many by the use of wrist watches during the War)

and continued himself to wear the pocket watch which we see in this early photograph?