As always, dear readers, welcome.

Looking back on nearly 500 postings, I see that names have popped up as a subject more than once. As far back as 26 August, 2015, there was “What’s In a Name?”, a title which turned up again on 27 July, 2016. Then there was “In a Name”, 2 March, 2022, and “Name of the Game, Game of the Name”, 10 May 2023.

And here is that theme again, the title coming from an old British Army expression, “No Names No Pack Drill”. A pack drill was a fairly mild form of punishment, in which the offender was assigned a certain number of hours of sentry-go while wearing a pack which had been especially heavily-weighted (bricks being one possibility).

(Imagine wearing this, loaded with bricks, and marching back and forth with it on your back for hours)

Thus, if the sergeant in charge of discipline had no name reported to him, the offender escaped.

It’s clear, however, that I can’t escape names, something which I find students struggling with when we read the Odyssey and suddenly they’re confronted with Agamemnon

(about to become “the late Agamemnon”, murdered by his wife and her BF)

and the suitors of Penelope, with names like Antinoos (an-TI-noe-os) and Eurymachos (eh-oo-RUH-mahk-os—that is, an-TIH-noe-os and eu-RIH-makh-os, in English),

(and more mayhem—about to become “former suitors” thanks to Odysseus and his son, Telemachos—teh-LEH-makh-os)

or Beowulf, with names which look quite unpronounceable, like that of Beowulf’s father, Ecgtheow (EDGE-theh-oh).

(Not Ecgtheow, but Beowulf himself, when he first encounters a Danish coast guard—this is from the era of illustration when anyone vaguely Norse was required to wear a helmet decorated with wings or horns)

Tolkien had become accustomed to those Greek names when still a school boy, writing to Robert Murray, SJ, in a letter of 2 December, 1953: “I was brought up in the Classics, and first discovered the sensation of literary pleasure in Homer.” (Letters, 258)

Names in Homer can sometimes seem very appropriate—Antinoos, one of the leaders of Penelope’s suitors and a definite villain, has one that can mean “he who sets his mind in opposition” and the ocean-going magical people who finally send Odysseus back home, the Phaiakians, often have names like Pontonoos, “he whose mind is on the sea” or Nausithoos, “Swift-ship”. Sometimes they seem puzzling: why is the other leader of the suitors called Eurymachos, “he who fights broadly/widely” when he has, as far as we know, never done any fighting at all? And why is that Cyclops called Polyphemos, “the very-well known”? If he were, why would Odysseus have visited him, lost six of his crew to the Cyclops’ voracious appetite, and barely escaped by hiding under a sheep?

Although Tolkien, as an undergraduate at Oxford, was seduced away from Classics, as he tells us in a letter to W.H. Auden of 7 June, 1955 (see Letters, 312-313) by other languages (Welsh, Finnish), a process begun even earlier with Anglo-Saxon and Gothic, I would suggest that his early association with Homer and the possibilities which names might present, both as to character and to language, endured. As he says in the same letter:

“All this only as background to the stories, though languages and names are for me inextricable from the stories. They are and were so to speak an attempt to give a background or a world in which my expressions of linguistic taste could have a function. The stories were comparatively late in coming.”

(This interest in naming could also lead him to be critical of another fantasy writer, E.R. Eddison, 1882-1945,

of whom he wrote “I read his works with great enjoyment for their sheer literary merit…Incidentally, I though his nomenclature slipshod and often inept.” From a letter to Caroline Everett, 24 June, 1957, Letters, 372. You can see what you think about Eddison’s way with names by reading The Worm Ouroboros, 1922, here: https://ia801304.us.archive.org/10/items/1924EddisonTheWormOuroborus/1924__eddison___the_worm_ouroborus.pdf )

For JRRT, then, names were as crucial to the text as the plot and, as a long-time reader of his work and as someone who has spent an equally long time studying and teaching languages, I find that my admiration for his care and patience in developing them has grown with my reading. It’s no wonder, for example, that he is so up in arms at the Dutch translator of The Lord of the Rings, who thought not only to translate the text, but the toponyms (place names) as well:

“In principal I object as strongly as is possible to the ‘translation’ of the nomenclature at all (even by a competent person). I wonder why a translator should think himself called on or entitled to do any such thing. That this is an ‘imaginary’ world does not give him any right to remodel it according to his fancy, even if he could in a few months create a new coherent structure which it took me years to work out.” (letter to Rayner Unwin, 3 July, 1956, Letters, 359)

And there, in that phrase, “coherent structure”, you see what Tolkien was always aiming for: his names, both of places and people, had to be consistent not only with the language they spoke, but also with the culture in which they lived—horse people like the Rohirrim can have names like Eowyn, perhaps ”delight in horses” and Eomer, “famous for horses”—and the history in which they lived. (And, as JRRT pretended that his Middle-earth work was translated, he then had the added fun of turning original names he had invented, like those of Banazir and Ranugad, into what he said were their English equivalents, “Samwise” and “Hamfast”—Sam and the Gaffer. See “Banazir and Ranugad”, 11 November, 2020 for more.)

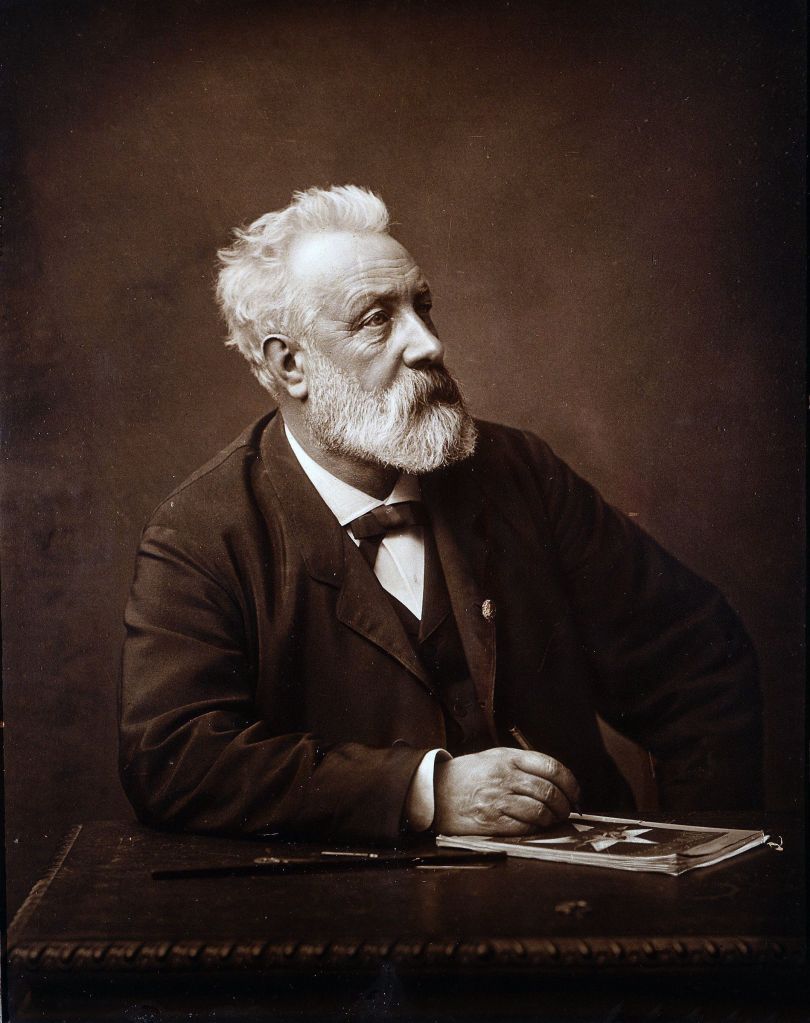

If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you probably will remember that, some time last spring, I decided that my knowledge of the history of science fiction was not what I would like it to be, and so I began a long-term project of going at least back to Jules Verne (1828-1905)

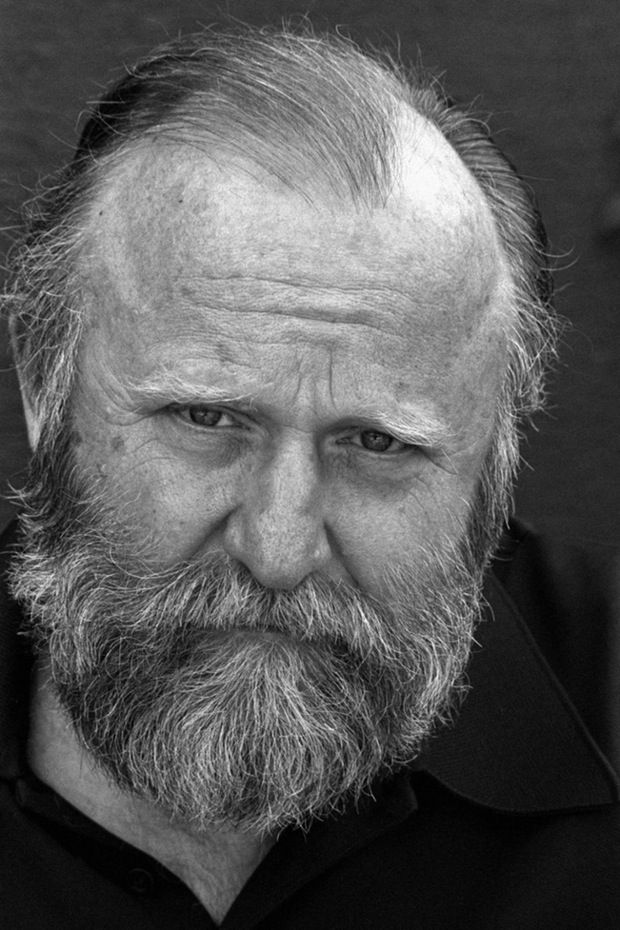

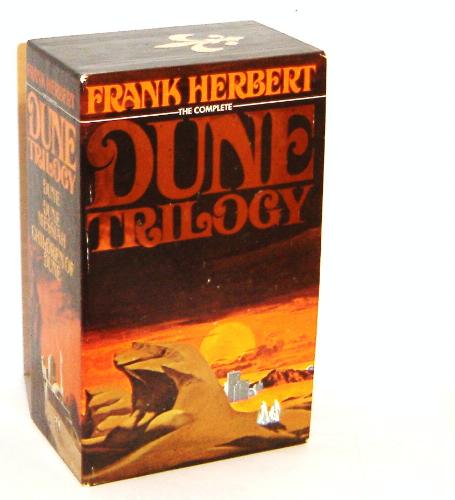

and reading—or rereading—as widely as I could, including translations from other languages, to give myself as wide an experience as I could. So far, I’ve added about three dozen books and a number of short stories to my ongoing bibliography with an uncounted number to go, but I admit that I’m not systematically chronological and recently, I decided to reread Frank Herbert’s (1920-1986)

original Dune trilogy (1965-1976).

I’ve only begun, and I’m finding it as complex and interesting as I remembered it, but, trained by JRRT, I was struck by what seemed like a very odd soup of names—Bene Gesserit, Muad’Dib, Shaddam IV, Atreides, Paul, Duke Leto, Jessica, Mother Gaius Helen, Thufir Hawat, and, strangest-sounding to me of all, Duncan Idaho—all within the first 30 or so pages. Some of the names were very familiar—Atreides is “the family of Atreus”, which includes the ill-fated Agamemnon and his less-than-distinguished younger brother, Menelaus. Leto, to me, isn’t a duke, but the mother of Apollo and his twin sister, Artemis. Gaius (also spelled Caius) is a common male Roman praenomen, that is, first name, as in Caius Iulius Caesar, or the emperor we commonly call by his childhood nickname, Caligula, who was another C/Gaius. Muad’Dib, with its glottal stop marker, suggests Arabic and Shaddam makes me think Persian (especially as he’s called Padishah, Persian “master king” so “king of kings”). Duncan Idaho? Duncan is an Anglicized version of Irish/Gaelic Donnchadh, about which there is scholarly disagreement (see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duncan_(given_name) ) Idaho—well, see this: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Idaho And then there’s Bene Gesserit. Bene is a Latin adverb, “well”. Gesserit is either the 3rd person singular, future perfect active indicative, or third person singular, perfect active subjunctive of the verb gero, with a variety of meanings around the idea of managing something, as in the standard phrase bellum gerere, “to wage war”. Thus, as a phrase, it should mean either “he/she/it will have managed well” or “she/he/it would have managed well”.

Tolkien was a science fiction reader himself (see Letters, 530 and “Sci-Fi”, 22 September, 2021), so I wonder, knowing how he felt about a certain creative lack in Eddison, what he would have said about this soup?

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

Manage things well,

And remember that there’s always

MTCIDC

O

PS

For more on names in Homer, Tolkien, and elsewhere, see “In a Name”, 2 March, 2022, here: https://doubtfulsea.com//?s=whats+in+a+name&search=Go