As always, dear readers, welcome.

As much as Tolkien, with justification, I think, denied external, historical influences on his work (and especially so, when, for example, it was suggested to him that the Ring was a stand-in for the atomic bomb—although he makes a grim reference to that possibility in a letter of 24 October, 1952, to Rayner Unwin—see Letters, 239), still, he was a highly intelligent, thoughtful, and sensitive man in a very complex era, one haunted, in part, by the disaster of 1914-1918, with its approximate 30,000,000 casualties,

(Tyne Cot Cemetery in southern Belgium, a heart-breaking place with 11,965 graves, of which 8,369 are of soldiers never identified)

and the understandable fear of another such which would bring as much, if not more, ruin, as that war had brought about even more destructive weapons than the later-19th-century machine gun—war in the air, including the first hint of terror bombing

and the extensive use of chemical weapons. (For more detail, see: https://www.britannica.com/story/the-great-war-infographic-of-deaths-and-milestones )

(The brilliant society and landscape painter, John Singer Sargent’s“Gassed”, 1919)

Thus, when I recently re-read this passage, it set me to thinking:

“The Rabble of Gondor and its deluded allies shall withdraw at once beyond the Anduin, first taking oaths never again to assail Sauron the Great in arms, open or secret. All lands east of the Anduin shall be Sauron’s for ever, solely. West of the Anduin as far as the Misty Mountains and the Gap of Rohan shall be tributary to Mordor, and men there shall bear no weapons, but shall have leave to govern their own affairs. But they shall help to rebuild Isengard which they have wantonly destroyed, and that shall be Sauron’s, and there his lieutenant shall dwell: not Saruman, but one more worthy of trust.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 10, “The Black Gate Opens”)

The seemingly-doomed expedition to confront Sauron has marched out of the ruined Minas Tirith

and north, to the Morannon, the Black Gate,

(the Hildebrandts)

where it meets an emissary, the Mouth of Sauron.

(by Douglas Beekman. This scene is badly mismanaged in the Jackson film, with the emissary being struck down, which is a gross violation of the chivalry which stated that such emissaries were protected by custom—of which the Mouth of Sauron, flinching, reminds Aragorn–and is far from what JRRT wrote.)

The Mouth of Sauron believes he has shaken Gandalf and his allies when he has presented them with what appears to be Frodo’s “Dwarf-coat, elf-cloak, blade of the downfallen West” and he suggests that the owner will be in torment for years unless they yield to Sauron’s terms—which Gandalf, after seeming to waver, then rejects, saying to Sauron’s emissary, “Get you gone, for your embassy is over and death is near to you.”

In the course of their brief dialogue, however, Gandalf has raised a point which made me think of an historical bargaining session, something Tolkien would have read about in the newspapers and seen in newsreels in the cinema, a meeting in late September, 1938, in Munich, Germany, among Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Edouard Daladier, and Neville Chamberlain.

Hitler had already assimilated Austria in March, 1938, during the event called the Anschluss (AHN-shluss, literally, in German, a “connection”)

and was now aiming to do the same to the young state of Czechoslovakia. That lurking fear of another war was behind the West’s scramble to do something to stop a new conflict brought about that meeting, as well as the so-called “Munich Agreement”, then signed by the four representatives, which, basically, handed Hitler much of Czechoslovakia, while signaling that the Western allies weren’t willing to fight to keep him from grabbing the rest.

And here we see a difference between Sauron and Hitler. When Gandalf says to the Mouth of Sauron:

“And if indeed we rated the prisoner so high, what surety have we that Sauron, the Base Master of Treachery, will keep his part?”

The reply is:

“Do not bandy words in your insolence with the Mouth of Sauron!…Surety you crave! Sauron gives none. If you sue for clemency you must first do his bidding. These are his terms. Take them or leave them.”

Hitler had said that he would be satisfied and even signed an agreement, separate from the Munich Agreement, with Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister, which included these words:

“” … We regard the agreement signed last night and the Anglo-German Naval Agreement as symbolic of the desire of our two peoples never to go to war with one another again”.

And Chamberlain took this back to London, waving it over his head at the airport in a famous gesture as he addressed a crowd.

You can hear Chamberlain address that crowd here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WMtG38ZKf3U

(As you can imagine, this is an extremely simplified version of events. If you would like to have a much more detailed version, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Munich_Agreement )

The worth of Hitler’s words came quickly: in March, 1939, he invaded the remaining portion of Czechoslovakia.

In September, 1939, he invaded Poland and World War II, which the West had compromised itself to avoid, would begin.

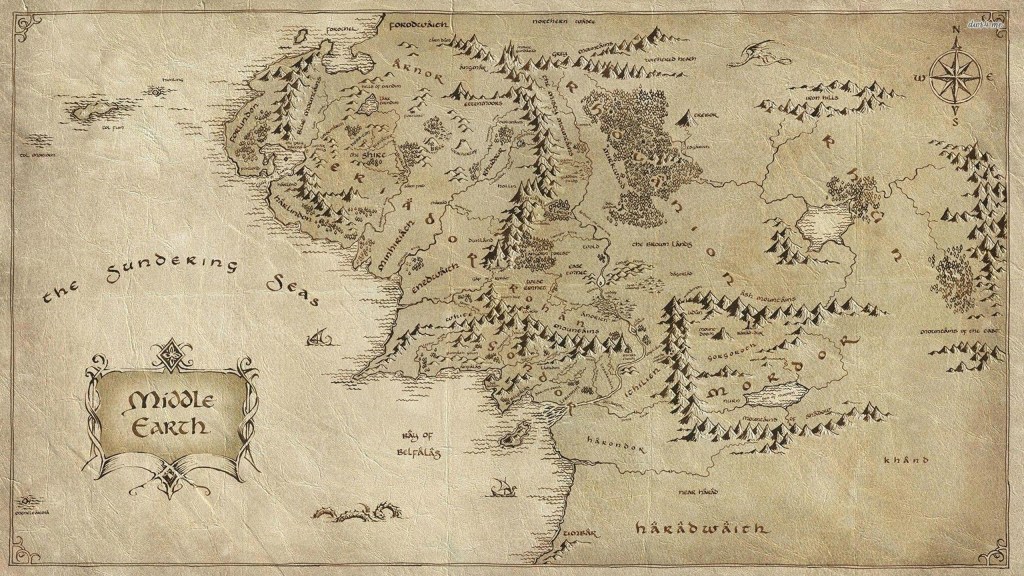

Looking at the map of Middle-earth,

we can see that Sauron’s terms would have:

1. reduced Rohan and Gondor to puppet states, to be ruled over by Sauron’s viceroy

2. stripped them of all future power to resist whatever that viceroy (meaning Sauron, of course) would have demanded, for all that the terms said that they could rule themselves.

What happened in Munich in September, 1938, rather than stopping a coming war, simply told the one who would pursue that war that the West was willing to sacrifice a great deal—even another country—to keep the peace. Was Tolkien at least marginally influenced by all of this? And, in a terrible “What If?” can we imagine a West had Gandalf and his allies given in to Sauron’s terms? Would Sauron have been content?

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

Beware the promises of dictators,

And know that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

As this is the first posting of the new year, as gloomy as this is, I don’t want it to suggest an omen. I’ve written that John Singer Sargent was, along with being a society painter, a landscape painter, usually in water colors, so here’s one of my favorites as, I hope, a more cheerful theme for the year to come—“Palms”, 1917