Welcome, dear readers, as ever.

As I’ve written before, one reason why I return to Tolkien again and again is that his richness provides so many subjects to write about. Often they are episodes or characters, but, occasionally, they are simply phrases and, in teaching The Hobbit this time, one phrase I’d never thought about before suddenly stood out and puzzled me with its odd, rather over-the-top exclamation.

When I was growing up, I lived in a valley which was shaped rather like an elongated bowl. It had that shape because it was the bed of an ancient lake, whose legacy to farmers and gardeners who lived and worked there was, below a thin layer of soil, a much deeper layer of sheets of petrified mud—shale.

There are places where shale contains oil, which would make it of some value in this fossil-fuel world (which JRRT so disliked) in which we live.

Ours, fortunately or unfortunately, was just very old, very hard, mud and a curse to dig through.

Because of the shape of the valley, it was also an attracter of lingering thunderstorms,

which, especially in midsummer, could sit over the valley for hours. We, therefore, had a lightning rod attached to our chimney,

which was actually once struck, when there was a tremendous BANG! but the rod did its job, guiding the lightning to the ground and our house didn’t burst into flame.

(This reminds me of Ray Bradbury’s wonderful novel, Something Wicked This Way Comes, 1962,

with its character, Tom Fury, the lightning rod salesman, which you can read a summary of here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Something_Wicked_This_Way_Comes_(novel)#Plot_summary There’s also a very good, if very different, treatment of the story in the 1983 Disney film of the same name.)

Having had some real-life experience, then, of lightning, it’s not surprising that, in school, I was struck (pun intended) by this image in an old school book–

It was identified as Benjamin Franklin, and he seemed to be out of his mind—flying a kite in an electrical storm?

It turns out, of course, that this was part of a science project, by which Franklin wanted to prove that what shot out of the clouds was, in fact, electricity. You can read more about his experimentation and theories here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kite_experiment And you can read Franklin’s first report of this particular—and ground-breaking—experiment from Franklin’s own The Pennsylvania Gazette for 19 October, 1752, here: http://www.benjamin-franklin-history.org/kite-experiment/ . His personal experience with lightning also made Franklin perhaps the first to suggest, in 1753, that one might, using an iron rod and a wire, divert lightning from buildings and even ships. Franklin’s suggestion is quoted in this same article as that which quotes his report of his experiment. (You’ll note, by the way, that the artist for that school book image doesn’t seem to have read the 1752 article, as Franklin stresses that the holder of the kite string needs to be indoors and Franklin himself was standing in a barn when he performed this experiment.)

Franklin’s experiment was part of a trend, beginning in the 1740s, towards better understanding lightning, as part of the general strong interest in science which was part of the Enlightenment. Earlier people in the West had a very different view, however, which often tied thunder and lightning to divinities. Ancient Greek stories include that of Asclepius, the son of Apollo and a brilliant physician,

who, when he began to restore the dead, was struck down by a “thunderbolt”,

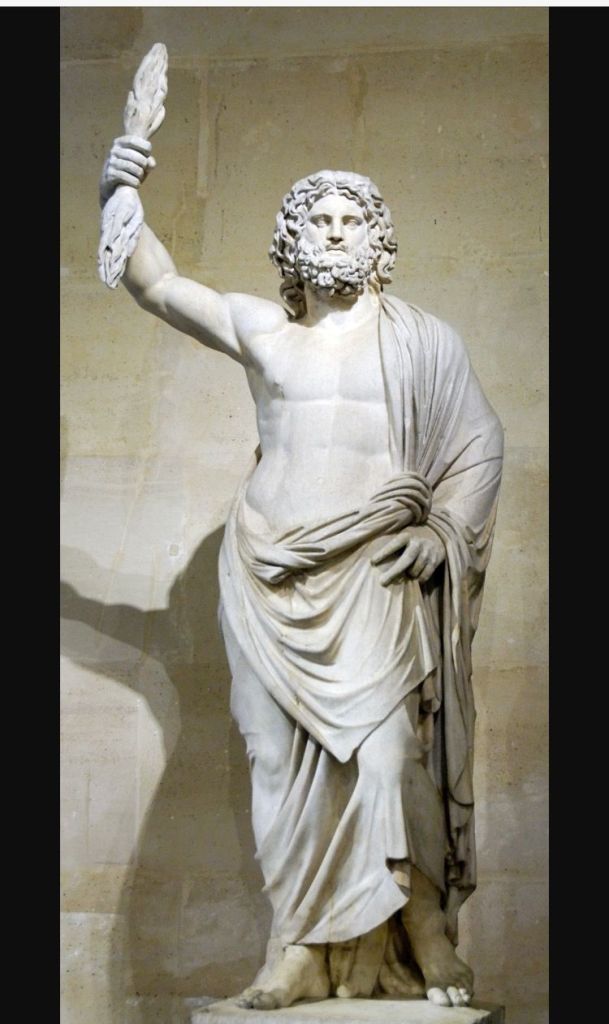

the weapon of choice of his own grandfather, Zeus.

This belief in Zeus’ electric power was shared by the Romans, in their version of Zeus, Jupiter,

as we can see in Ovid’s (43bc-17/18ad) treatment of the story of Semele, in Book 3 of his Metamorphoses, where he repeats the Greek myth of Semele, a sometime-gf of Jupiter, who was tricked by Juno into asking him to show her his real form,

with its drastic consequences:

est aliud levius fulmen, cui dextra cyclopum 305

saevitiae flammaeque minus, minus addidit irae:

tela secunda vocant superi; capit illa domumque

intrat Agenoream. corpus mortale tumultus

non tulit aetherios donisque iugalibus arsit.

“There is another, lighter thunderbolt, to which the right hand of the Cyclopses

Has added less of ferocity and flame, less of fury:

They call these the secondary weapons of the god. Those he takes and enters

The Agenorean house. The human body did not endure

The divine tumult and blazed with the husbandly gifts.”

(Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book 3, lines 305-309, my translation—Agenor was Semele’s grandfather)

(There is a very lush opera on the subject by George Frederick Haendel (1685-1759) from 1744 which goes into extended detail about events. There’s a summary of the plot here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semele_(Handel) and a performance here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FibDMWk0i5k , and, as well, you can hear probably the most famous aria from this opera, “Where E’er You Walk” (sung by Jupiter to Semele in Act 2, Scene 2) sung by one of my favorite tenors, John Mark Ainsley, here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BYOZnwQQV18 )

All of this brings me back to the what seemed an odd turn of phrase in Chapter 1, “An Unexpected Party” of The Hobbit. After much food and some moody music,

Thorin has been talking quite frankly about the expedition to the Lonely Mountain, but the real gravity has only struck Bilbo—

“Poor Bilbo couldn’t bear it any longer. At may never return he began to feel a shriek coming up inside, and very soon it burst out like the whistle of an engine coming out of a tunnel. All the dwarves sprang up, knocking over the table. Gandalf struck a blue light on the end of his magic staff, and in its firework glare the poor little hobbit could be seen kneeling on the hearth-rug, shaking like a jelly that was melting. Then he fell flat on the floor, and kept on calling out ‘struck by lightning, struck by lightning!’ over and over again; and that was all they could get out of him for a long time.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 1, “An Unexpected Party”)

What is going on here? Why such an extreme reaction? Bilbo’s attitude towards the dwarves and their plan has fluctuated during their stay: he has been appalled by their aggressive behavior as guests and seduced by their haunting song, but, when Thorin has begun to unroll the actual facts of their scheme, he has been moved to a new level of resistance as the truth of what they’re planning comes clearer—

“Gandalf, dwarves and Mr. Baggins! We are met together in the house of our friend and fellow conspirator, this most excellent and audacious hobbit—‘…He paused for breath and for a polite remark from the hobbit, but the compliments were quite lost on poor Bilbo Baggins, who was wagging his mouth in protest at being called audacious and worst of all fellow conspirator, though no noise came out, he was so flummoxed.”

Is what Bilbo actually experiencing and expressing, an English expression, “a bolt out of the blue”? A useful website, “The Phrase Finder”, says that this expression appears to be rather comparatively recent, first traced to Thomas Carlyle’s (1795-1881) The French Revolution, 1837, (oddly exactly a century before the initial publication of The Hobbit) where there is found:

“Arrestment, sudden really as a bolt out of the Blue, has hit strange victims.”

The meaning is “a sudden unexpected event” and the website then takes it back I think quite believably to Horace (65-8bc) and an ode, Number 34 in Book 1. This begins with the idea that the speaker has been lax in his religious observances, but, thanks to a sudden meteorological occurrence, he is changing his ways:

…namque Diespiter 5

igni corusco nubila dividens

plerumque, per purum tonantis

egit equos volucremque currum,

“for Father Jupiter,

Generally splitting the clouds with flashing fire,

Drove his thundering horses and his winged chariot

Through [a] clear sky…”

(Horace, Odes, Book 1, Number 34, lines 5-8, my translation)

As Horace has been unpleasantly surprised by Jupiter, might we then imagine Bilbo, coming close to being brought into the dwarves’ plan, then suddenly caught by Thorin’s grim “may never return” have suffered a similar epiphany, almost as if he, too, had almost been “Struck by lightning, struck by lightning!”? Considering all that is about to happen to him in the course of The Hobbit, perhaps Bilbo’s outburst isn’t so over-the-top after all.

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

Keep making sacrifices to Jupiter,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O