Tags

Welcome, as ever, dear readers.

In Narnia, when does The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe actually take place? In the outside, historical world of England, all we’re told is that the children who are the main characters, Peter, Edmond, Susan, and Lucy, are sent into the country “because of the air-raids”. (The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, I, “Lucy Looks into a Wardrobe”), which could have been any time between September, 1940 and May, 1941. I would suggest that C.S. Lewis has quietly offered us an answer to my question– in the season we’re currently in.

At least two members of the Inklings, the informal Oxford literary group which met regularly at various places in town and the university in the 1930s and 1940s, mention Christmas in their fiction. One, Tolkien, following, perhaps, his later plan to keep overt religion out of his work, calls it “Yule” in The Hobbit, the other, C.S. Lewis, mentions it boldly and in a very interesting way which combines his Christianity with a very different set of beliefs, of which I’m sure he was aware, in The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe (1950).

Narnia is ruled by Jadis, the White Witch (and remember that name—Jadis is French jadis, “formerly”)

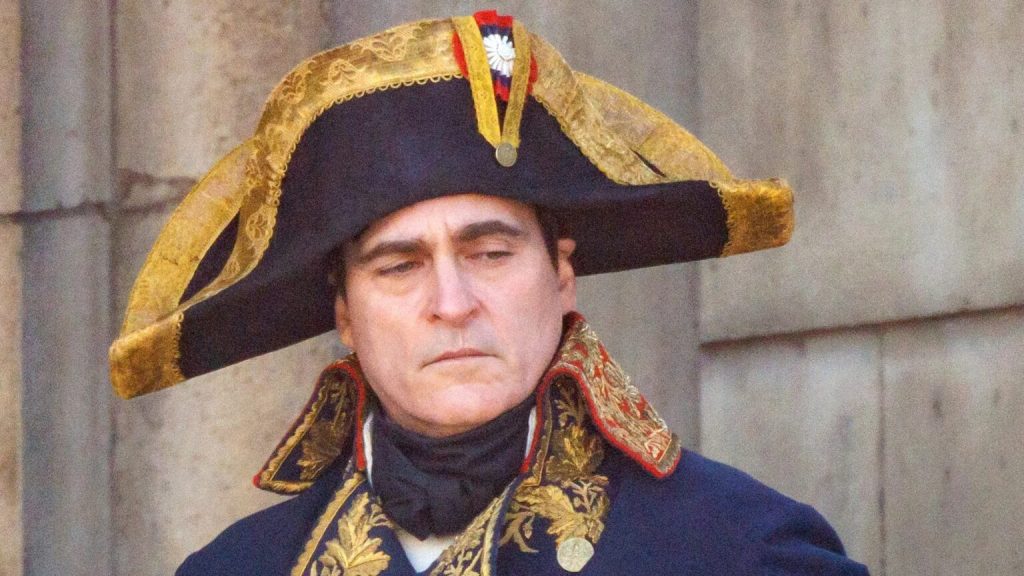

(Pauline Baynes)

and, to keep it under her sway, it is (literally) frozen in time—and this is where that mention comes in, as Mister Tumnus, a faun,

(another Baynes)

explains to Lucy, who has accidentally strayed into Narnia:

“Why, it is she that has got all Narnia under her thumb. It’s she that makes it always winter. Always winter and never Christmas; think of that!” (The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, II, “What Lucy Found There”)

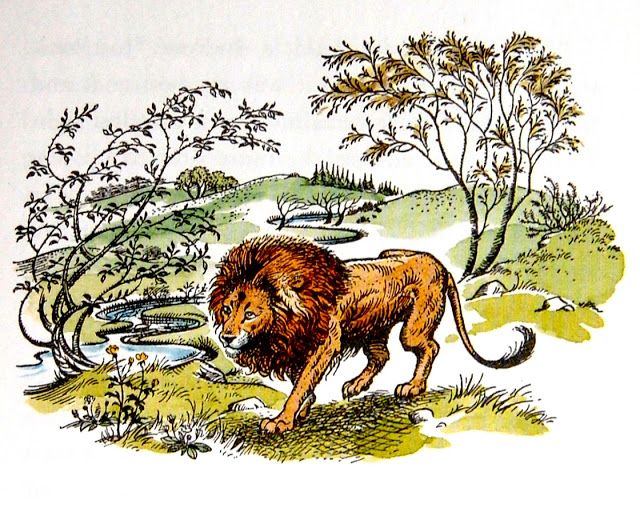

As Jadis’ power wanes, with the resurrection of Aslan, the great lion,

(and a third Baynes)

this is embodied in two events:

1. the world begins to thaw

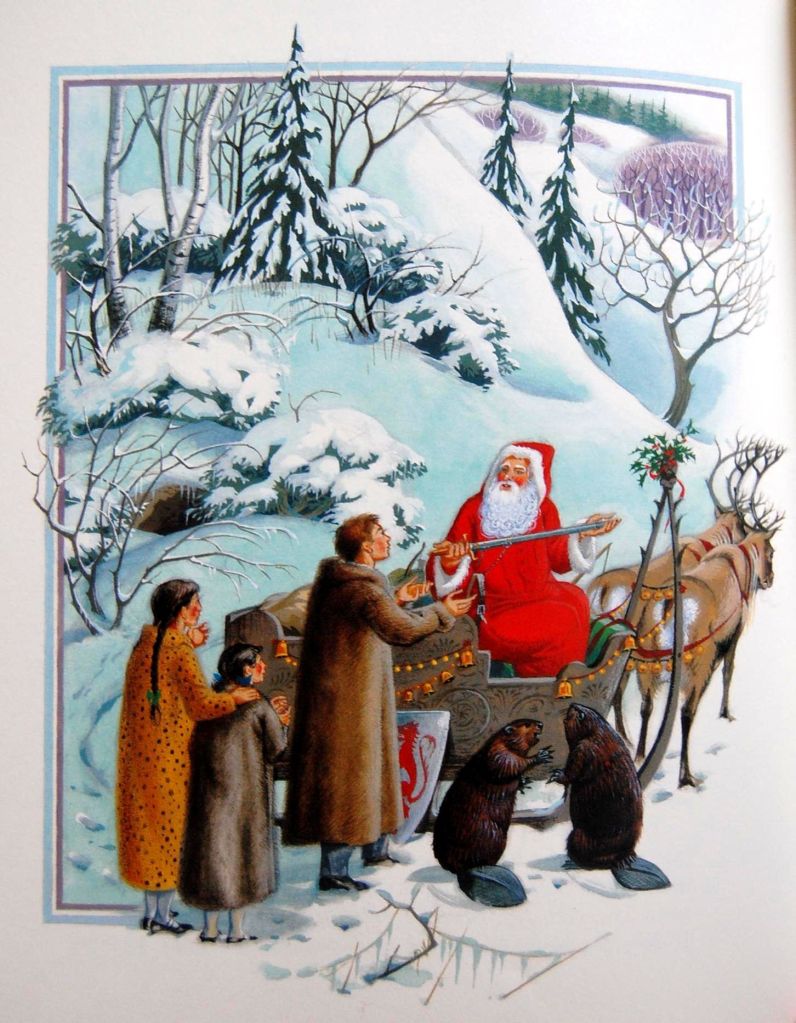

2. Father Christmas appears at last (and, significantly, brings tools for the fight against Jadis and her allies)

(and a final Baynes)

With Father Christmas appears Christmas and time, which has seemingly come to a halt, can begin to function again, as winter once more has its Christmas in its proper place, which would signal, along with the thaw, that the year was no longer blocked by Jadis.

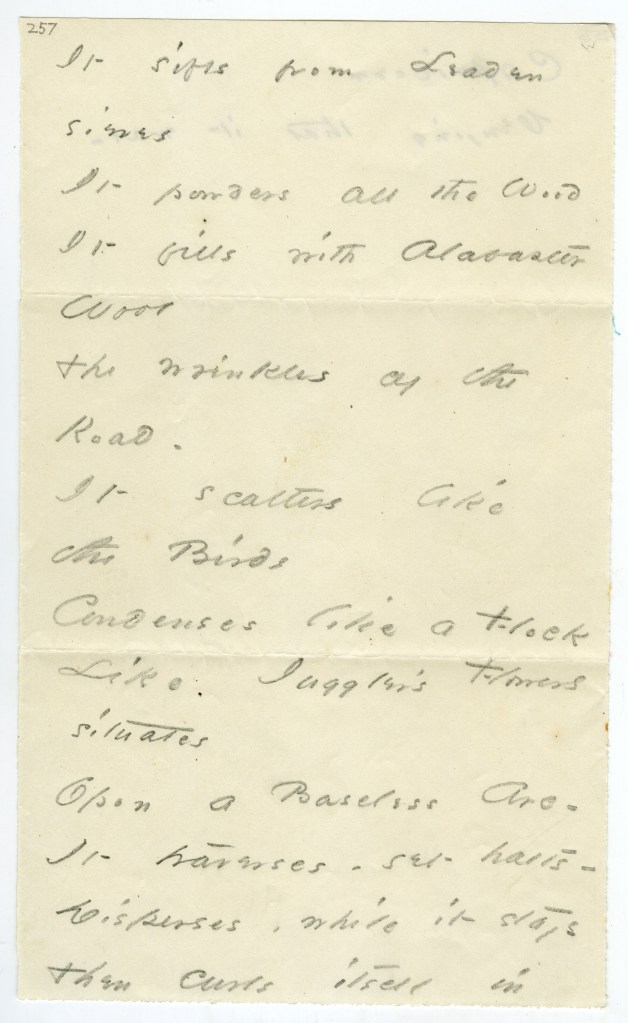

For Christians, of course, the coming of Christmas means the coming of Jesus, when time begins all over again—hence the older “B.C/” (“Before Christ”) and “A.D.” (Anno Domini, “In the Year of the Master/Lord”) used in Western countries to mark the centuries of earthly existence—for much more on this see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anno_Domini . For early Christians, then, Jesus’ birthday should happen at a moment which signals a major change in the year, just as the coming of Aslan means a major change both in the season and the governing of Narnia. The date ultimately selected by early Christians first appears in The Chronograph of 354, a collection of late-Roman calendar information. In Part 8, there is an extensive list of the original chief officers of the Roman state, the consuls (who were elected in pairs), by whose 1-year term in office Romans commonly dated events during the Republic. Here, under the consulship of “Caesar” and “Paulus” it reads:

Hoc cons. dominus Iesus Christus natus est VIII kal. Ian…

“At this time/date, [these being] the consuls, the lord Jesus Christ was born 8 days before the kalends of January…” (that is, 25 December—the consuls for that year—which would become 1AD—were Gaius Caesar, the Emperor Augustus’ grandson, 20BC-4AD, and Lucius Aemilius Paullus, before 29BC-14AD, married to the Emperor Augustus’ granddaughter, Julia—my translation)

(You can read the dating here: https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/chronography_of_354_08_fasti.htm There is a further identification of this birthday in Part 12, in a calendar of early Christian martyrs, as well.)

In Tolkien’s Yule, and even in that 25 December, however, we see the celebration of change older than the date established in the Chronograph. (For more on Yule see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yule For more on Tolkien and Yule, see: https://doubtfulsea.com//?s=yule&search=Go )

In Part 6 of this same Chronograph, which is a general yearly calendar, we find, for the 25th of December, a day devoted to “Invicti”–“of the Unconquered”–and here may lie an explanation as to why this day in particular was chosen.

I’m writing this on the day of the Winter Solstice, which gives the title to this posting in a translation of an Old English term for this time of year, sunstede, linguistic cousin to the Latin term, solstitium, from sol, “sun” and the verb sisto, “come to a stand, make to stand”. Today is the shortest day of the year and perhaps, because night seems to stay forever and day seems so short, the name was originally based upon a lingering fear that the sun would freeze in place, having come to a permanent standstill.

(Traditional people around the world once imagined that something like that might have happened to the sun during solar eclipses and performed all sorts of rituals to make the sun continue to perform as it should. See: https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2017/08/solar-eclipse-awe-wonder-and-belief/ for an interesting article on folk beliefs and practices around eclipses.)

For the Romans, the Solstice appeared in the midst of a major holiday, the Saturnalia, celebrated from the 17th to the 23rd of December (although the number of days varied in different periods of the Roman empire),

a festival in honor of the ancient god, Saturn.

Because he was so ancient, the Romans had all sort of ideas about him and his history and even what his name was derived from. One definition comes from Cicero’s (106-43BC) De Natura Deorum, linking Saturn with the Latin word satis, meaning “enough”, implying that Saturn, being somehow the consumer of time, was its controller,and that seems to fit him and his holiday very nicely in with the Solstice:

Saturnum autem eum esse voluerunt qui cursum et conversionem spatiorum ac temporum contineret…

“They wished Saturn to be the one, moreover, who preserves/holds back the movement and change/rotation of intervals and of seasons…” (Cicero, De Natura Deorum, Book II, XXV—you can read that here: https://archive.org/details/denaturadeorumac00ciceuoft/page/184/mode/2up –my translation)

The Saturnalia, then, was a celebration of the shift from one season to another as the sun, rather than stopping, would continue to move towards spring.

In 274AD, the late Roman emperor, Aurelian (c.214-275AD),

attempted to refocus polytheistic Romans upon a single god, Sol Invictus, “the Unconquerable Sun”.

He built an immense elaborate temple, perhaps a little bit of which survives in the crypt of the Church of San Silvestro

in the heart of Rome, and declared that 25 December was the god’s official birthday—a convenient day as it was just at the end of that big winter festival, the Saturnalia, in which a god of change and, at that time of year, seasonal change, were celebrated, Aurelian placing the sun he wanted Romans to focus upon in their worship right at the end of that festival and just after the beginning of that change (the actual solstice is on or about 21 December). For early Christians, then, what better day to pick for their special birthday?

C.S. Lewis, then, thinking in Christian terms (he once suggested that stories like the Narnia books might be a way to present Christianity to children—see his essay: “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s to be Said” , to be found in the collection Of Other Worlds ), brought together winter, Jadis, (and remember that her name means “formerly/in the past”, indicating her soon-to-be position in time), Father Christmas, and Aslan to rewrite, in his fairy tale, the celebration of an seasonal event by the Romans in a festival in the time of the solstice, as well as a late (soon, to Christians and to Rome in general, jadis) Roman deity’s birthday and perhaps to answer my initial question, as well: in Narnia, it may be Christmas.

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

Io Saturnalia!

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O