As always, welcome, dear readers.

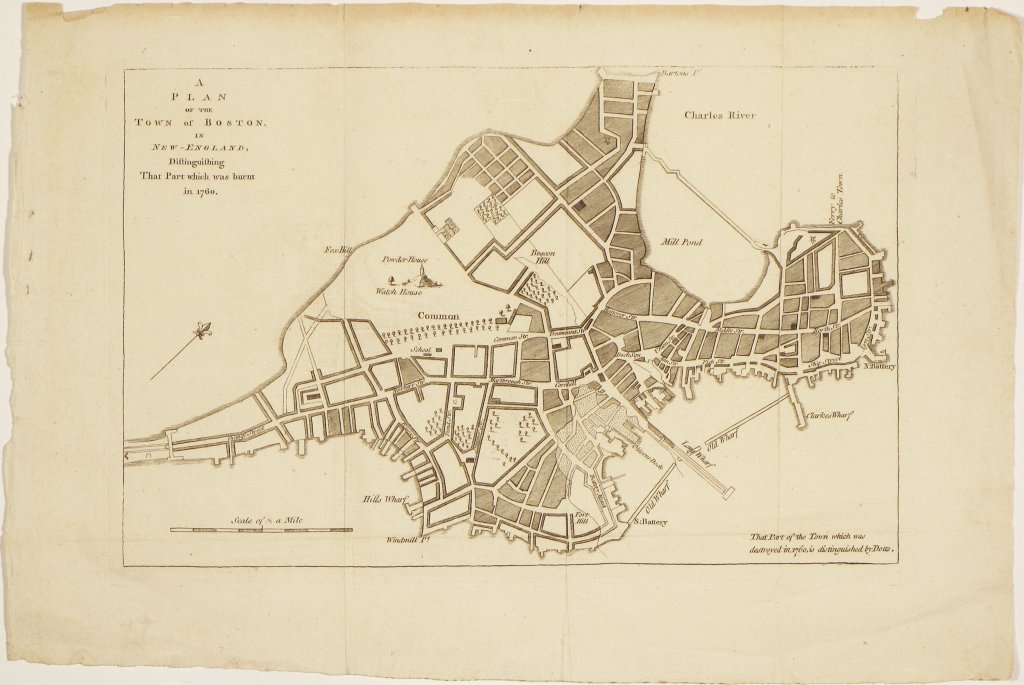

Boston, in the late 1760s, was a turbulent place.

It shouldn’t have been surprising, as its founders had been dissenters from Charles the First’s absolutist ideas of religion

who, forming a corporation, had come to New England to found their own state, which they had run independently from 1630 to 1686, when a royal governor, Sir Edmond Andros,

was sent to rule, but lasted only three years before politics in England changed things until 1692, when Massachusetts became a royal colony for good—or at least until 1775.

A major difficulty was what seemed to be an endless quarrel between Massachusetts merchants and the government in London about the regulation of trade, which began as early as 1651, when Parliament instituted the first of four Navigation Acts.

The title you see here says it all: “An Act for Increasing of Shipping, And Encouragement of the NAVIGATION of this NATION”, the nation here being Britain—and only Britain, its colonies in North America, then really Masschusetts Bay, Plymouth, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Virginia, being viewed only as sources of revenue, not as part of Britain—the original cash cows—

By law, exports and imports were to be strictly limited to English ports, dealing directly with other countries being prohibited.

Smuggling, of course, immediately commenced,

but never could replace legitimate trade—and things got worse after the British victory in the Seven Years War (1756-1763—here in the US 1754-1763), when Britain, having plunged deeply into debt to defeat its enemies, was faced with the need to pay back the huge loans it had taken out.

It undoubtedly sounded logical to those in the government that, as part of the war had been waged to defend the North American colonies from the French and their Native American allies,

(Eugene Leliepvre, one of my favorite French military artists)

those colonies should help with that enormous debt. From the other side of the Atlantic, Massachusetts, along with others of the English colonies, long resenting earlier attempts to control colonial trade, and having a tradition of their own elective assemblies,

felt that such an expectation should come with some formal influence in Parliament—the well-known complaint of “taxation without representation”.

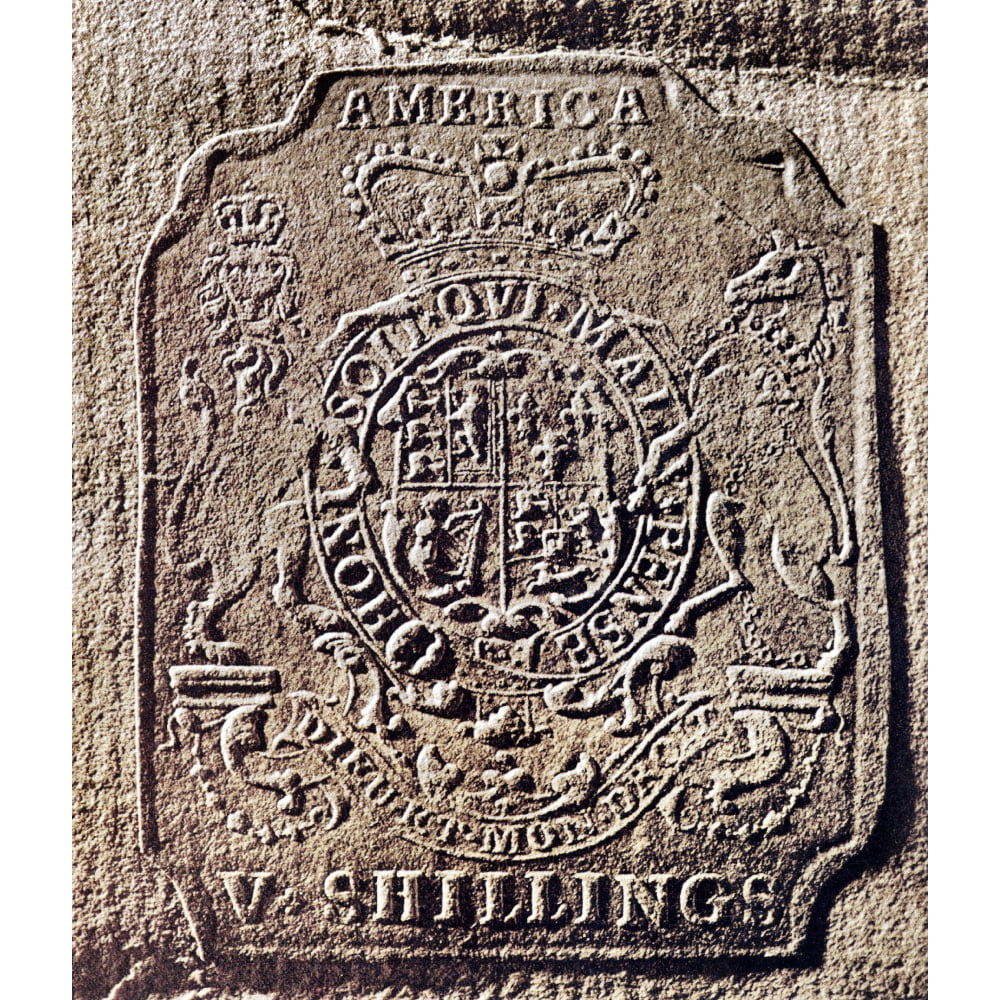

Foolishly, this complaint was ignored by those at the top, who, instead, began to issue, from 1763 on, a whole series of Acts designed to extract funds from the colonies, usually involving either domestic imports or even, in the Stamp Act of 1765, colonial documents (all legal papers had to bear a government tax stamp to be legal—and not only legal papers, even newspapers and playing cards came under this Act).

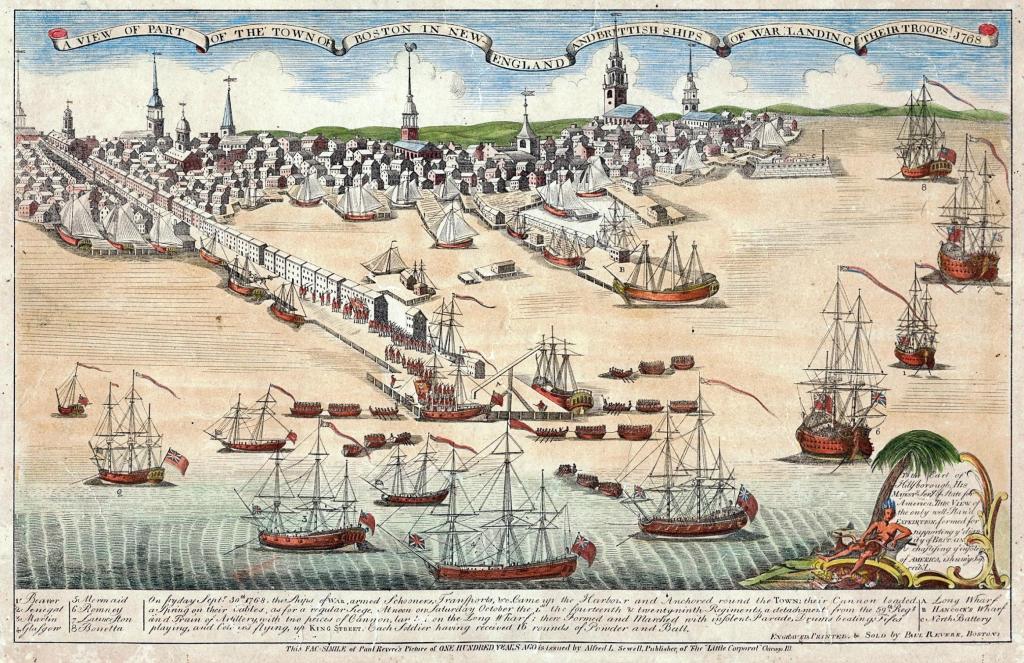

Needless to say, the tension could only grow and, in 1768, the government in London felt that it was necessary, to enforce its acts and to protect its officers, to send troops to Boston.

As the caption tells us, when the troops landed, they did so as if they were conquerors come to occupy enemy territory: “there Formed and Marched with insolent Parade, Drums beating, Fifes playing, with Colours flying, up KING STREET…”—with the most ominous addition: “Each Soldier having received 16 rounds of Powder and Ball”—that is, these men were ready for a fight, if necessary.

The population of Boston in 1768 was about 16,000, with no barracks and few public spaces besides its churches, so the addition of, eventually, 4 regiments of infantry—perhaps as many as 2,000 men, all told–would have put a strain on the town even if these had been welcome new inhabitants. The soldiers were quartered in taverns, barns, stables, and whatever empty buildings might be found, but soon, as might have been expected, began to tussle with the locals, which led to open bloodshed in March, 1770, when a panicked squad of soldiers fired into a mob which seemed to be threatening them—the so-called “Boston Massacre”, as depicted in Paul Revere’s propaganda print, with its “Butcher’s Hall” over the doorway behind the troops—in case you might have missed the point.

(a more accurate, but no less bloody, depiction by the famous contemporary American military artist, Don Troiani)

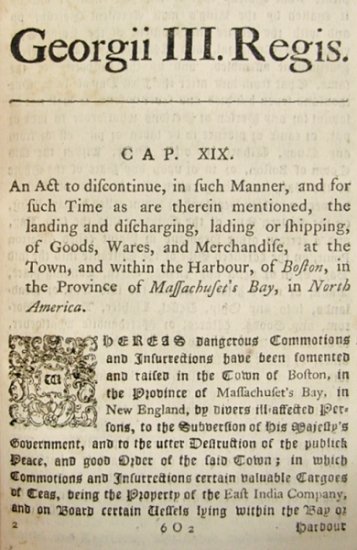

Such violence on the part of what locals viewed not as their own government’s soldiers, but as occupiers, only made things worse and, although there was no second “massacre”, more attempts by the London government to squeeze profit from the colonies finally led to the destruction by locals of a large shipment of taxable tea, dumped into Boston harbor in December, 1773—the “Boston Tea Party”.

This was too much for London and the decision was made to send more soldiers, remove civilian control, and set a military governor, Thomas Gage, already commander of British troops in North America, over the town.

In an even bigger blow, the government officially closed the port of Boston, setting warships to block the harbor.

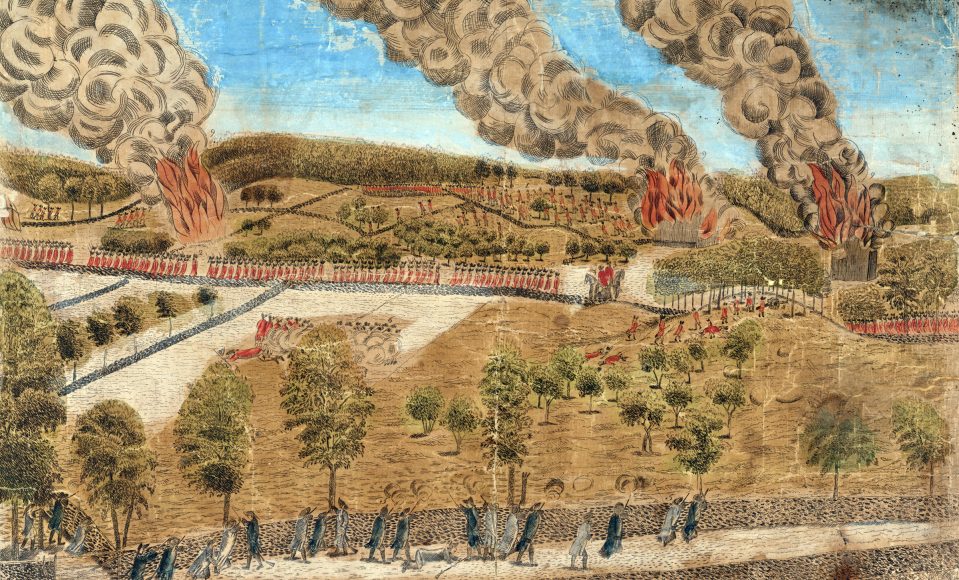

Gage would then be pressured, both by government in London and by those loyal to the Crown in Boston, to do more to deal with what appeared, increasingly, to be a movement towards armed rebellion, leading to the British troops’ disastrous expedition to seize military supplies and local leaders west of Boston at Concord in April, 1775, leading to an estimated 300 British casualties and about 100 locals

(another Don Troiani)

and a siege of Boston so intense that the British were forced to evacuate the city the following March.

(H. Charles McBarron—America’s first great military historical artist of the 20th century)

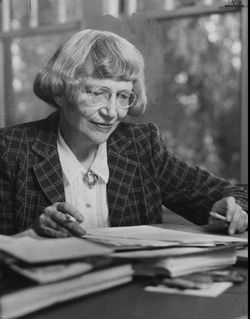

All of this forms the background to a YA novel I’ve just been rereading, Esther Forbes’ (1891-1967) 1943

Johnny Tremain.

Johnny is an orphaned young Bostonian apprenticed to an elderly silversmith during the early 1770s and the book follows both the course of history in which he’s involved, as well as his own rather difficult personal life. I very much recommend this book, but I don’t want to do a SPOILER ALERT, so I’ll just say that what makes it stand out for me is that the author is at great pains to depict Johnny’s development, from an arrogant boy with ambitions to a virtual outcast to someone who combines humility with a moving understanding of the people around him, including some of those who had given him difficulties in his growing up.

Forbes herself wrote other historical novels set in early New England, as well as Paul Revere and the World He Lived In, 1942, which won her the Pulitzer Prize for History in 1943, and which clearly explains the authentic feel of Johnny Tremain.

As the book has so many dramatic elements—from 1770s Boston and its tensions to Johnny’s personal struggles—it’s not surprising that Walt Disney studios made a film of the novel in 1957.

As the book is complex, this is a very simplified version, stripping away many of the characters, but keeping most of the major moments, although, for the sake of colorful action, where Forbes had kept Johnny in Boston during the events of April, 1775, the film sends him to Lexington and Concord and follows the action there through him, including the British retreat to Boston through intensifying sniper fire from the locals.

(from a set of four engravings made after the events by Amos Doolittle, oddly, like Johnny—and Paul Revere–a silversmith who had taught himself engraving—see this article about him for more: https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/amos-doolittle-connecticuts-paul-revere/ )

Although not so mature as the book—and pretty sloppy on things like British uniforms and clothing of the period in general, though with very good sets—it’s a fun movie, which does capture some of the spirit of Forbes’ novel and, along with that novel, I would recommend it. For more on events of this period, particularly military, I would also recommend the American Battlefield Trust website—you can read it here: https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/lexington-and-concord

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

Always demand representation,

And remember that, also as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O