Welcome, dear readers, as always.

When I was a child, I loved nursery rhymes, but sometimes the words puzzled me.

“Ride a cock horse

To Banbury Cross…”

What was a “cock horse”?

As a grownup, I can gather a great deal of information to try to explain, but it’s complex, including a possible first appearance of the rhyme in Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book, 1744, although this is from a reconstruction from later texts of Volume 1, as what survives is only Volume 2.

Banbury is a town northwest of London.

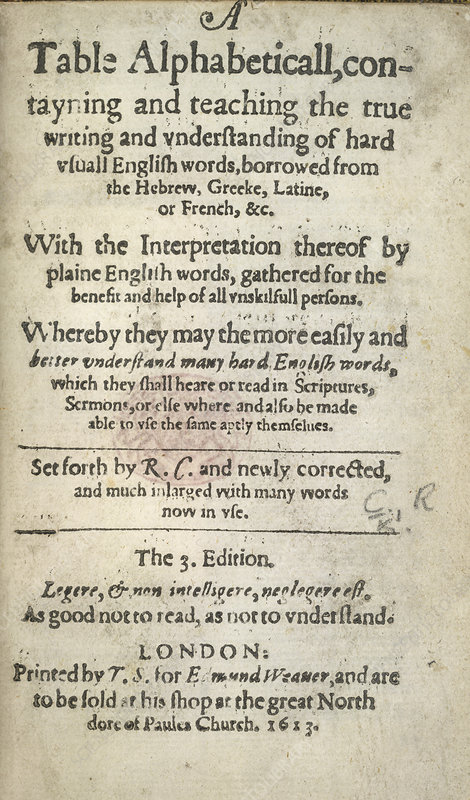

A cock horse? I checked the earliest mono-lingual English dictionary, Robert Cawdrey’s Table Alphabeticall, 1604, and found nothing (if you would like to see this early work, look here: https://extra.shu.ac.uk/emls/iemls/work/etexts/caw1604w_removed.htm )

(As you can see, this was clearly a popular book, this being the 3rd edition, of 1613.)

Consulting dictionaries near-contemporary to Tommy Thumb, we find:

1. Nathan Bailey’s ( ?-1742) Dictionarium Britannicum, 1730-36, defines “cock-horse” as “a high horse” ;

(You can consult Bailey here: https://archive.org/details/b30449698/page/n185/mode/2up )

2. Dr. Samuel Johnson’s (1709-1784) A Dictionary of the English Language, 1755,

defines “cockhorse” (which he indicates is to be accented on the first syllable) as “on horseback; triumphant; exulting” (you can see this definition here: https://johnsonsdictionaryonline.com/views/search.php?term=cock This site contains the several early editions of the dictionary, including both in modern type and as they appear in those editions—if you enjoy such things, this is simply lots of fun to browse.)

If you do a quick WIKI search, you discover: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ride_a_cock_horse_to_Banbury_Cross , which presents several other possibilities, including, “a high-spirited horse, and the additional horse to assist pulling a cart or carriage up a hill. It can also mean an entire or uncastrated horse”. None of these struck me as quite the appropriate definition, but this one: “From the mid-sixteenth century it also meant a pretend hobby horse or an adult’s knee.” seemed more like it. I know this as a “dandling song”, a game played with babies and small children. There are a good number of them, usually with rhythmic but sometimes nonsensical lyrics, like

“To market, to market,

To buy a fat pig.

Home again, home again,

Jiggety, jig.

To market, to market,

To buy a fat hog.

Home again, home again,

Jiggety jog.”

And you can see what happens: bouncing a small person on your knee to the rhythm. Unfortunately, the WIKI only cites Iona and Peter Opie’s 1951 The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes for this definition, and, for the moment, I can’t trace that meaning back any farther, as I don’t have a copy of the Opies’ book readily available.

But this leads me to another mysterious nursery rhyme:

“Bat, bat,

Come under my hat

And I’ll give you a slice of bacon.

And when I bake,

I’ll give you a cake,

If I am not mistaken.”

Although I have an ecologist friend, whose main work is on bats and loves, them, I’m afraid that I don’t share this affection. And here’s why—

(If you, dear reader, like my friend, are fond of flittermice, I apologize. Too much Dracula in childhood, I suspect!)

But, as a child, I wondered: why would you want a bat under your hat? And do bats actually eat bacon? And cake?

The Baring-Goulds, in The Annotated Mother Goose, 1962, seem to think that this is a part of a children’s game, their only note being “Here the child who was hunting bats would clap hands.” Children hunting bats?

My hunting an early source for this nursery rhyme would seem to need more than hand-clapping. After a little survey of early collections, here’s what I found so far.

It’s not in the 1744 Tom Thumb’s Pretty Song Book,

or in

Mother Goose’s Melody, 1781 https://ia804703.us.archive.org/3/items/mothergoosesmelo00pridiala/mothergoosesmelo00pridiala.pdf (This is a 1904 reprint of the 1791 edition)

or in

Gammer Gurton’s Garland, 1784, https://archive.org/details/gammergurtonsgar00ritsiala/page/62/mode/2up (This is an 1866 reprint of the 1810 edition.)

but it does appear in the first edition of James Orchard Halliwell, The Nursery Rhymes of England, 1842, https://ia800301.us.archive.org/27/items/nurseryrhymesofe00hall/nurseryrhymesofe00hall.pdf (This is the 5th edition, of 1886. He also identifies it as a children’s game, and the Baring-Goulds are actually simply quoting him.)

(In case you’d like to serenade the bat, this has, in a version sung once upon a time in south Florida, a little tune. The recording, from 1940, is a little hard to make out, but it sounds like a close cousin of “Yankee Doodle”: https://www.loc.gov/item/flwpa000062/?loclr=blogflt )

This flurry of research began in a completely different place, however, with a possible anachronism in The Hobbit, which I’m currently teaching. JRRT himself was aware that there were a number of these in the 1937 edition of the text, and, in the 1966 edition, changed or considered changing a number of them, so that what was once “cold chicken and tomatoes” in 1937, then became “cold chicken and pickles”, for example. Some things remained, however, such as Bilbo’s scream, “like the whistle of an engine coming out of a tunnel”, and Douglas Anderson, in his invaluable The Annotated Hobbit, suggests that:

“This usage need not be viewed as an anachronism, for Tolkien as narrator was telling this story to his children in the early 1930s, and they lived in a world where railway trains were a very important feature of life.” (The Annotated Hobbit, Chapter One, “An Unexpected Party”, 47-48, note 35)

It’s clear that Tolkien himself must have had rather mixed feelings about this, however, allowing tobacco (although called “pipe-weed” in The Lord of the Rings) and potatoes (“taters” in The Lord of the Rings) to remain, but removing those tomatoes. He also considered replacing that engine with “like the whee of a rocket going up into the sky”, but, ultimately retained the railway image. (see Chapter One, “An Unexpected Party”, note 35)

What caught my attention was a simile in Chapter 8, where Bilbo and the dwarves, marching into Mirkwood, were assailed by night creatures, moths “nearly as big as your hand, flapping and whirring round their ears”—

“They could not stand that, nor the huge bats, black as a top-hat, either…” (The Hobbit, Chapter Eight, “Flies and Spiders”)

Was this Tolkien the 1930s narrator? Or was this allowed to stand, like potatoes and tobacco and the train, because he felt that it somehow fit the story? Or was this simply something he missed? I suppose that we’ll never know, as this is something that JRRT, unlike a bat, kept under his hat.

As ever, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

Ponder what recipe one might need for a bat cake,

And know that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

There is a very interesting article on Dr. Johnson, early English dictionaries, and his dictionary at: https://johnsonsdictionaryonline.com/blog/about-johnsons-dictionary/

PPS

For more on hobby horses, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hobby_horse_(toy)