As always, dear readers, welcome.

My last two postings have discussed the idea of the mythic/folkloric figure sometimes referred to as “the king under the mountain”, who, the story goes, instead of dying, seems either to take himself off or is carried off to another place, where he stays, usually sleeping, until some need awakens him (often his native land is in danger) and he will return to the world of the living to save the day.

In my latest teaching, however, which includes both the Odyssey and The Hobbit, people definitely return, but the day does not quite go as planned.

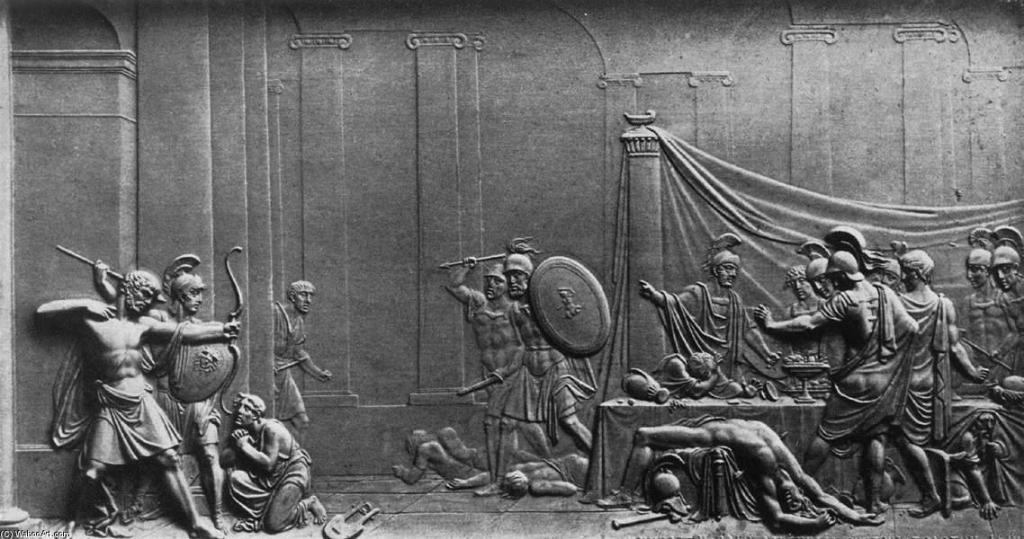

Although Odysseus is the main character of the Odyssey, a figure who haunts the text is Agamemnon, the Greek high king, who organizes the expedition to Troy. While he is gone, his wife, Clytemnestra, is seduced by Agamemnon’s cousin, Aegisthus, and, upon Agamemnon’s return, he and his men are lulled into a false sense of security by Aegisthus at a banquet and then murdered.

(This is a depiction—on the right—of an alternate version of Agamemnon’s death, just after leaving a bath—and, on the left, the death of Aegisthus some years later by Agamemnon’s son, Orestes. It’s on a red figure krater, a wine-mixing bowl, at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. You can learn more about it here: https://collections.mfa.org/objects/153661 )

Why should this man, now long dead and far from Odysseus’ home on Ithaka, be such a dominant figure in the story?

Odysseus was reluctant to go off to the Trojan War. To escape, he pretended to be mad, plowing the beach of his home island, Ithaka, as if it were real arable land—and doing so with the combination of a mule and an ox–

The Greeks might have believed in his insanity if another Greek, Palamedes, hadn’t intervened, snatching up Odysseus new-born son, Telemachus, and putting him directly in Odysseus’ path. Odysseus swerved, of course, but this suggested that he wasn’t so mad as he looked and soon he was off on a boat for Asia Minor. (In several later stories, Odysseus gets his revenge by planting evidence that Palamedes was actually in the pay of the Trojans and he dies in several unpleasant ways: stoning and drowning. As the ancient Greek travel writer, Pausanias, c.110-c.180AD, tells us that Palamedes had invented dice, we might think that he would have been a bit more careful about chance! This is in Pausanias’ tour of Argos—The Description of Greece 2.20.3—which you can read in an English translation here: https://www.theoi.com/Text/Pausanias2B.html )

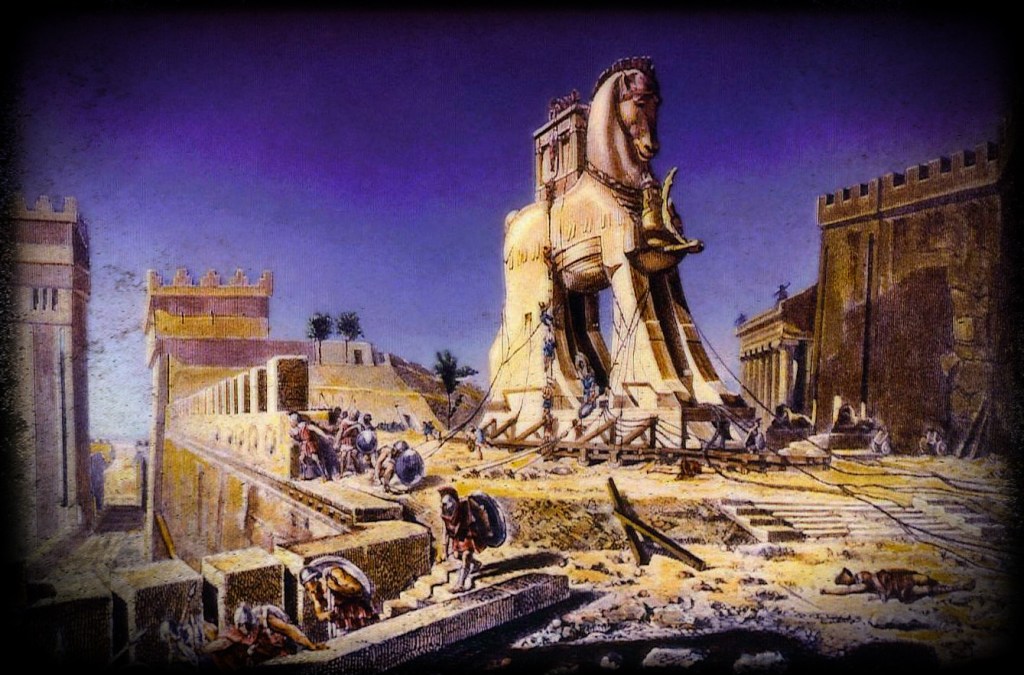

10 years go by, Troy falls, thanks to a trick which might have been invented by Odysseus himself,

but, for the Odyssey, that’s only backstory. Now Odysseus will spend another 9 years struggling to get home, slowed on his way by

1. eaters of a substance which makes people forget about going home,

2. a large hominid with one eye and a taste for human flesh,

3. a group of giants who eat most of Odysseus’ fleet,

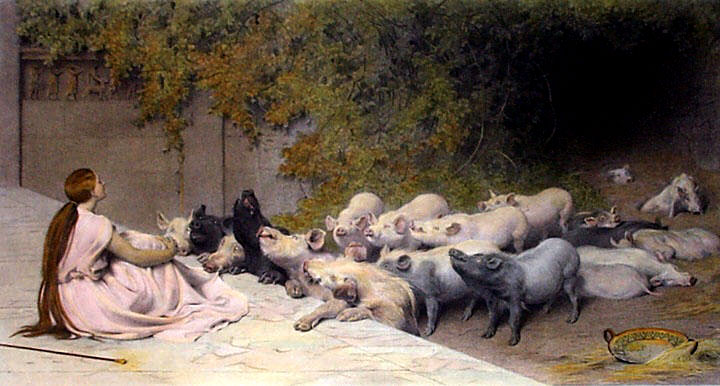

4. a sorceress who amuses herself with animal transformations,

5. not to mention a trip to the Land of the Dead,

6. Sirens,

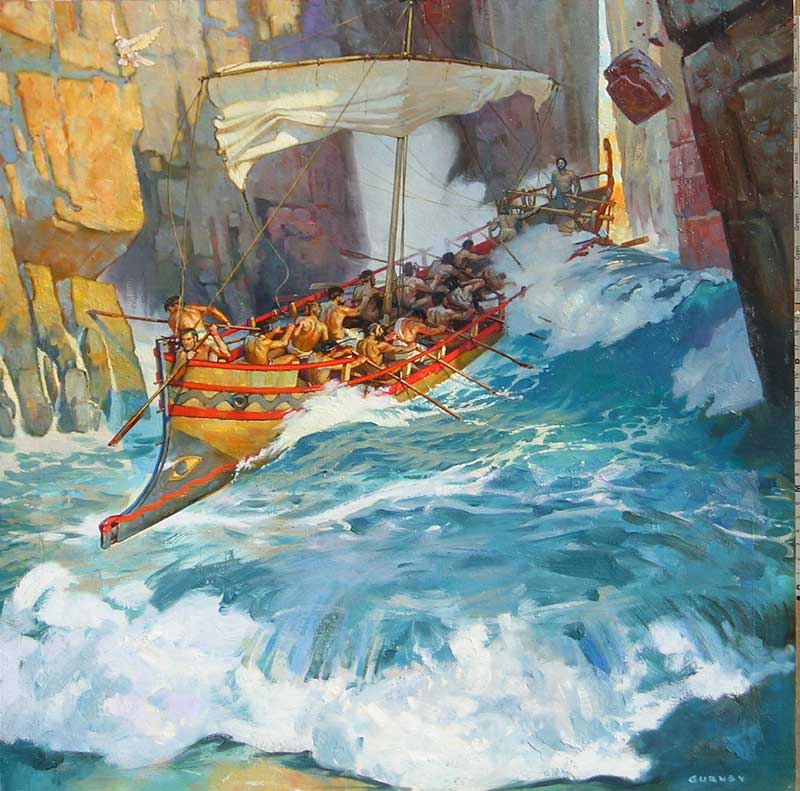

7. clashing rocks

(James Gurney—and what a beauty! Here’s his website for more: https://jamesgurney.com/ )

8. a thing with six barking heads across from a whirlpool,

(Stephen Somers—about as frightful as they come—here’s his website: https://stephen_somers.artstation.com/store/art_posters/Mokp/scylla-and-charybdis He’s the art director for Fantasy Flight Games, which might interest you, if you don’t know their work: https://www.fantasyflightgames.com/en/index/ )

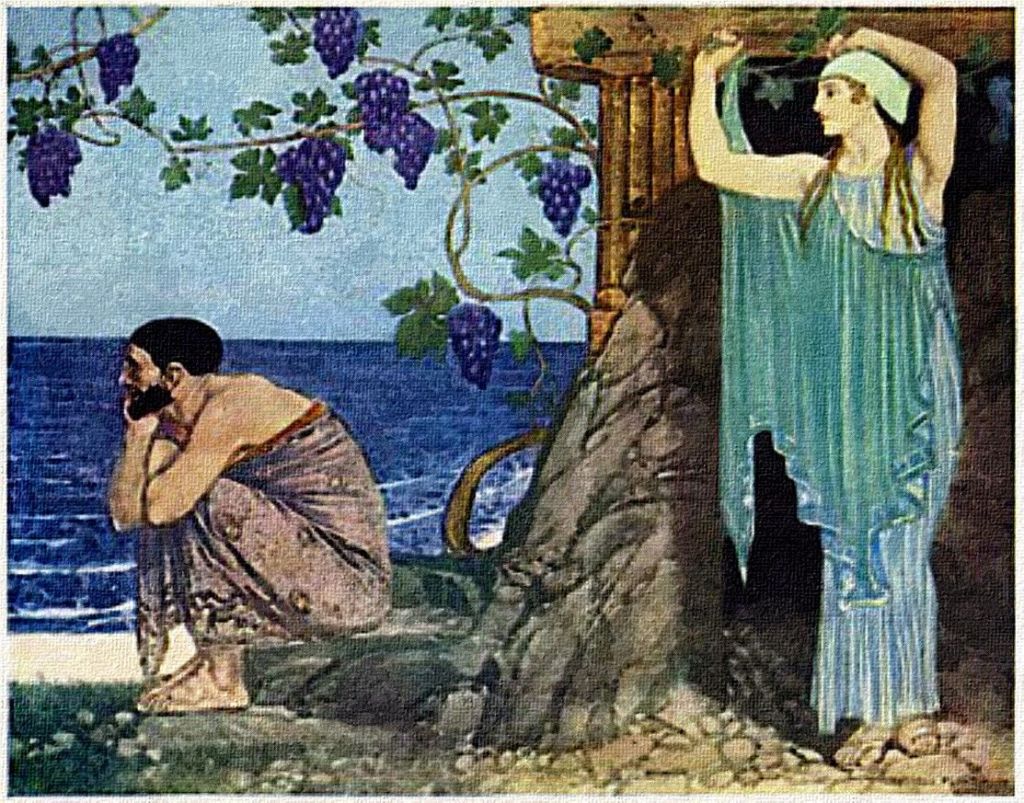

9. as well as a minor goddess, who keeps Odysseus as a prisoner on her island for 7 years.

Meanwhile, for the past 4 years, Odysseus’ home on Ithaka has been invaded by over 100 young local men who are in hot pursuit of Odysseus’ wife, Penelope.

(by John William Waterhouse, 1849-1917)

They are convinced—or at least pretend—that Odysseus is long dead and that Penelope, a widow, should marry one of them—which brings us back to the ghost of Agamemnon, which, as I said, haunts the Odyssey. Agamemnon left his wife to go off to Troy and, coming home, found himself betrayed and murdered. And, in the Troy tradition, he’s not the only one: another major Greek, often paired at Troy with Odysseus, is Diomedes—we see him here as he appears in Book 10 of the Iliad, when he and Odysseus make off with the horses of the Thracian prince, Rhesus, having killed the horses’ owner in the process.

Within the tradition of the Nostoi—that is the “homecomings” of the Greeks from Troy—there exists a version of the homecoming of Diomedes, which almost mirrors that of Agamemnon and might foreshadow that of Odysseus. While he was away at Troy, his wife, Aegialia, takes one of several possible lovers—or several at once—and, when he returns, Diomedes barely escapes with his life.

And so, through Agamemnon’s fate, the theme is set: what will happen to you when you come home after so many years away? Is your wife still faithful? Or will you suffer as Agamemnon did and Diomedes might have?

In fact, Penelope has been faithful these 19 years, even, when the suitors arrived nearly 4 years before, putting them off by explaining that, until she had finished weaving a shroud (burial garment) for her father-in-law, Laertes, (still quite alive) she can’t even think about remarrying. So she says. During the day, she weaves, but, during the night, she unweaves,

(This is the fragment of a needlework by Dora Wheeler Keith, 1856-1940, showing Penelope doing her un-doing. It’s in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and you can read about it here: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/16951 Dora and her mother, Candace, were remarkable craftspeople and you can read about them here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Candace_Wheeler and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dora_Wheeler_Keith There’s also the American impressionist William Merritt Chase’s beautiful portrait of Dora at the Dora Wheeler Keith wiki site)

continuing (literally) to string the suitors along for several years before one of her maids tells the suitors what’s really going on and they force her to finish. Thus, when Odysseus returns, although Agamemnon’s ghost makes a final reappearance near the very end of the story (Book 24) to discuss his own death, Odysseus is at least safe from his wife. The suitors, however, are another matter, but, with the inadvertent aid of Penelope, he—with his son, Telemachus, two loyal slaves, and Athena—defeats and kills all 100+. It’s a fairly complicated process, including what looks a bit like the archery contest in the Robin Hood story

(this is by NC Wyeth, 1882-1945—you can find my favorite edition of the Robin Hood story—illustrated by Wyeth here: https://archive.org/details/robinhood00cresrich )

or the Pixar movie Brave (2012),

but the story (nearly) concludes with a heap of dead suitors

(by Fyodor Petrovich Tolstoy, 1783-1873)

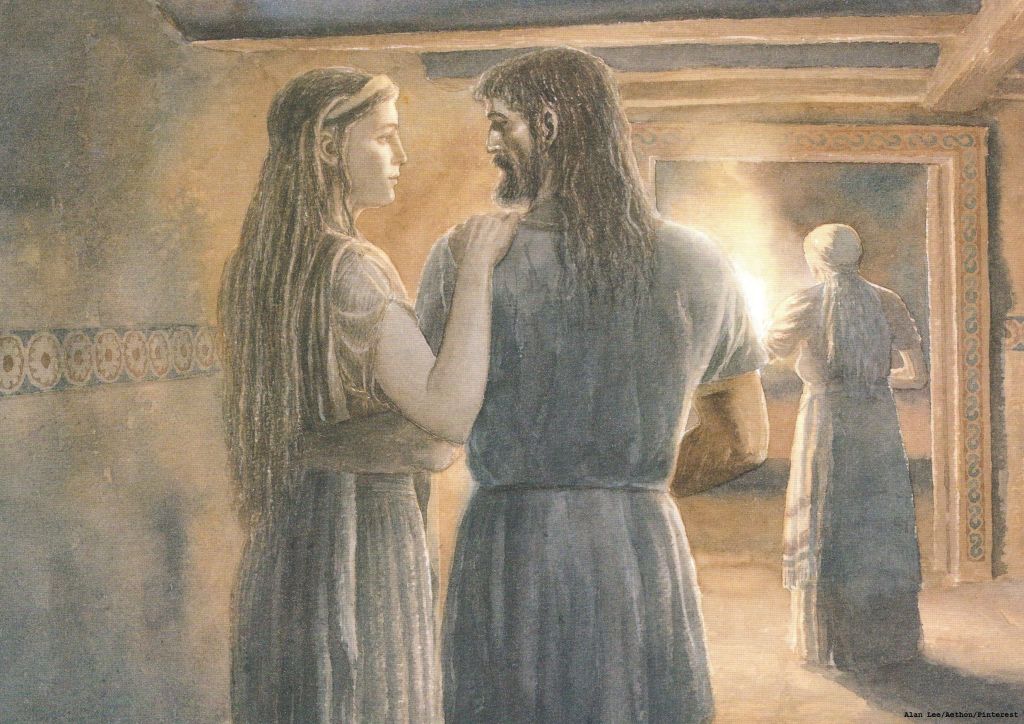

and the happy reunion of Penelope and Odysseus (which Athena thoughtfully prolongs by extending the night).

(by Alan Lee, who clearly does Homer just as well as he does JRRT)

But what about JRRT and his returns, happy or otherwise?

That’s for the second part of this posting.

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

Listen to ghosts—they may have good advice,

And remember, as well, that there’s

MTCIDC

O