As ever, dear readers, welcome.

It’s a sad fact, perhaps, but, sometimes, even authors we really enjoy don’t quite succeed and, with the best will in the world, it’s hard not to think, “I was following along and enjoying the book and then came the conclusion and…”

For me, in the latest read of my science fiction project, such was the case with Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp’s The Land of Unreason (first published in Unknown Worlds, October, 1941,

then expanded into book form in 1942).

It began with an interesting premise: an American in early wartime Britain, makes the mistake of violating the custom of leaving out food and drink for “the Good People” (that is, the “Fee”). This causes him to fall into a world in which “reason” has laws of its own and much of the fun, for me, was in watching the protagonist attempt to figure out how to deal with this. (You can read a full summary here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_of_Unreason ) It was a bit uneven here and there, but not enough to trouble, so long as it kept moving, but then came that ending, where the protagonist, “Fred Barber”, is revealed to be the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick I (also known as “Barbarossa”, 1122-1190)

(This is a reliquary—a place to store a sacred relic or two–and was supposedly modeled on old Fred himself—for more see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Barbarossa )

and there the story rather abruptly ends.

If you only knew that Frederick was the Holy Roman Emperor, this would be puzzling—why should that matter in resolving the plot?–but perhaps what the authors wanted the readers to remember is that Fred, as Frederick, belonged to a folklore tradition, called by the folklorist, Stith Thompson, “the Kyffhaeuser type” or “the king under the mountain” (also known as “the king asleep in the mountain” , No.1960.2 in Thompson’s motif index)

In this tradition, a once-famous culture hero, like Frederick, is said not to be dead, but, instead, away somewhere else, often sleeping, but, given the right moment—usually when his country is in danger–he will awaken, or be awakened, and then come to the rescue. Perhaps the authors were suggesting a sequel?

Legend has it, for example, that Frederick is drowsing under a German mountain, either the Untersberg, between Austria and Germany,

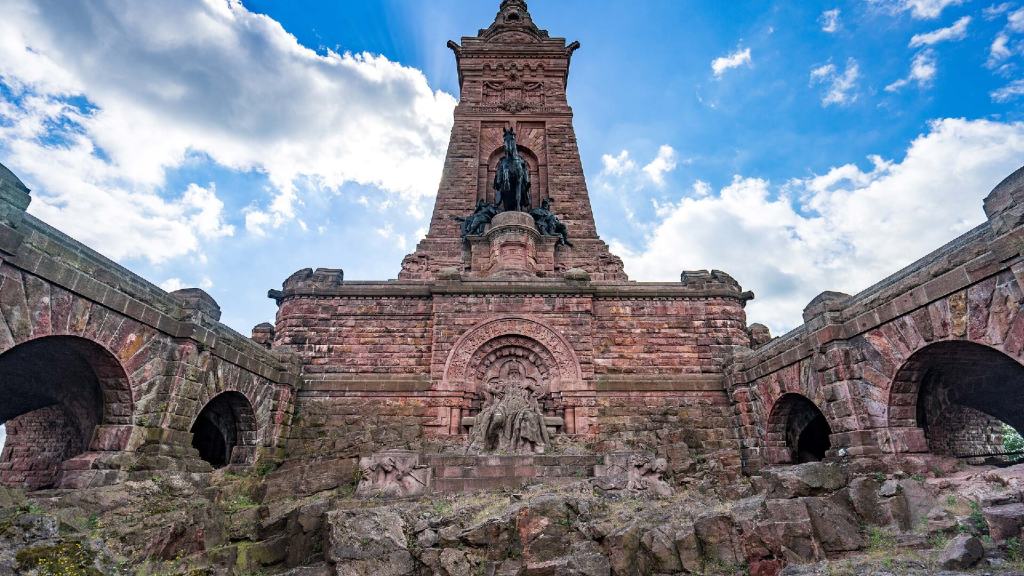

or the central German hill range of the Kyffhaeuser (hence Thompson’s name for the motif type).

The latter has been decorated—or marred, depending upon your taste—with a gigantic monument, dedicated in 1896, combining an image of Frederick, deep in slumber still, with an equestrian statue of Kaiser Wilhelm I (1797-1888) posed above him (the idea being that now there’s a German empire—ruled by Wilhelm I’s grandson, the erratic and trouble-making Wilhelm II—Barbarossa can continue to doze).

An interesting side detail about the Barbarossa story can be found in the Grimm brothers Deutsche Sagen, (“German Legends”) where it’s reported that when a dwarf led a shepherd under the mountain, Barbarossa stood up and asked, “Are the ravens still flying around the mountain?” At the shepherd’s affirmation, he cried, “Now must I sleep yet a hundred years longer!”

(Brothers Grimm, Deutsche Sagen, Number 23, Vol.1, page 30, my translation. You can find the text here: https://books.google.com/books?id=SRcFAAAAQAAJ&pg=PR1#v=onepage&q&f=false ) Those ravens will return in Part II.

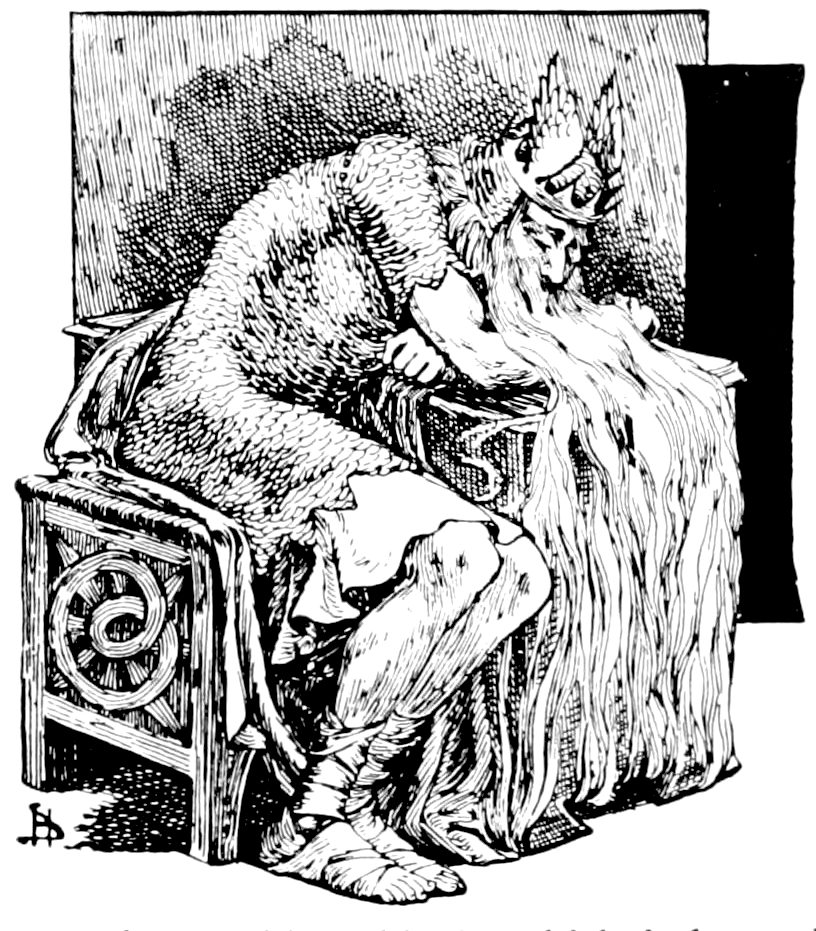

This motif is surprisingly common (there’s a whole WIKI article devoted to it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King_asleep_in_mountain ), including , in the West, everyone from Ogier the Dane, who is involved in the medieval Charlemagne stories

(and who even turns up the in a fairy tale of Hans Christian Andersen, from an 1899 translation of which this illustration appears—you can read it here: https://ia800505.us.archive.org/26/items/fairytalesofhans00ande/fairytalesofhans00ande.pdf )

to the early Irish hero, Fionn mac Cumhaill (who, in English, becomes ”Finn mac Cool”—if you’d like to read more about him, you might begin with Lady Gregory’s fiercely-named Gods and Fighting Men, 1913, available for you here: https://archive.org/details/godsfightingmens00greg )

to the South Slavic Marko Kraljevic (KRAL-jeh-vitch—“Kingson”, so, “Prince Marko” )

who has the most wonderful horse, Sarac (SHA-rats—in English “roan”, a sort of reddish-brown—although the word has a fairly wide meaning, and illustrations, like the one here, depict him as what appears to be what we’d call a “piebald”), with whom he shares his wine—you can read about them here: https://archive.org/details/BalladsOfMarkoKraljevic/page/n3/mode/2up Although, in this translation of ballads about Marko, he dies, after killing Sarac so that he can’t be turned into a beast of burden by Marko’s enemies. See this article for his sleeping, as well as the good news that Sarac isn’t killed: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_Marko )

to a very familiar figure, King Arthur.

Our earliest-known reference to Arthur’s disappearance, Geoffrey of Monmouth’s (c.1095-c.1155) Historia Regum Britanniae (“History of the Kings of Britain”, c.1130s), has only this to say:

Sed et inclytus ille Arturus rex letaliter vulneratus est, qui illine ad sananda vulnera sua in insulam Avallonis advectus,

“But that famous king Arthur was mortally wounded, too, and who was carried from there [Cornwall] for the healing of his wound to the island of Avalon…”

(Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historia Regum BritanniaeHistoria Regum Britanniae, Book XI, Chapter II, my translation—and you can read a very useful English summary/translation of the Arthurian bits of Geoffrey here: https://d.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/text/geoffrey This comes from the University of Rochester (NY, not UK), “Camelot Project”, which is invaluable if you’re interested in things Arthurian.)

By the late 15th century, it appears that this tradition has been extended and that it begins to have more the look of the “king under the mountain”:

“Yet somme men say in many partyes of Englond that kyng Arthur is not deed / But had by the wylle of our lord Ihefu in to another place / and men say that he shal come ageyn & he shal wynne the holy croffe . I wyl not say that it shal be so / but rather I wyl say here in thys world he chaunged his lyf / but many men say that there is wryton vpon his tombe this vers Hic iacet Arthurus Rex quondam Rex que futurus /”

(Sir Thomas Malory (? There is much discussion about who he was and when he lived, but a manuscript says that the text was completed by 1470), Le Morte d’Arthur, Book XXI, Chapter VII—this is from the 1889 edition of Oskar Sommer, which reprints the first printed edition of 1485 of William Caxton—and here it is for you: https://archive.org/details/lemortedarthuror00malouoft/page/n5/mode/2up If you read this blog regularly, you know that I always prefer the earliest edition of a work which I can find, as I believe that earlier English, both the language and the printing, is so much more interesting and memorable. )

(one of the only two copies of that first printing—it’s in the Morgan Library in New York)

That cross, with its inscription, is a monkish fake from 1190/1, (See a chatty but useful article here: https://arstechnica.com/science/2016/03/medieval-monks-used-king-arthurs-grave-as-an-attraction-to-raise-money/ as well as an article about all sorts of possibilities for Arthur’s burial here: http://www.badarchaeology.com/controversies/looking-for-king-arthur/the-archaeology-of-arthur/ ) but there seem to be two versions of it, one, reported by Gerald of Wales, c.1146-c.1223, in his Speculum Ecclesiae—“The Mirror of the Church”—Part II, Sections VIII-X , and presumably the earlier version, says nothing about “quondam” or “futurus”, that is, “one-time” and “to be” , quoting the inscription to say (my translation):

“Hic jacet sepultus inclytus rex Arturius in insula Avallonia cum Wennevereia uxore sua secunda”

“Here lies buried the famous king Arthur in the island of Avalon with Guinevere his second wife”

(You can find the full text in Latin here: https://ia902902.us.archive.org/10/items/giraldicambrensi04gira/giraldicambrensi04gira.pdf and an English translation of the relevant parts here: https://www.earlybritishkingdoms.com/sources/gerald02.html )

As you can see, no “quondam” (“one-time”) and no “futurus” (“to be”). So where did they come from? As far as we know, this appears only in Malory, although Malory cites “his tombe”. When the supposed Arthur was reburied, in the presence of Edward I and Eleanor of Aquitaine, in 1278, he was given what must have been a rather showy tomb—

(This is a reconstruction by the Department of Archeology at Reading, which has done major work for the study of Glastonbury from its ancient roots at least to the end of the ecclesiastical period. See: https://research.reading.ac.uk/glastonburyabbeyarchaeology/digital/arthurs-tomb-c-1331/arthurs-tomb/ )

Although, with the dissolution by Henry VIII of Glastonbury Abbey in 1539, the tomb was lost, but the early antiquary, John Leland (c,1503-1552), has left us a partial description in his Itineraries (notebooks of his travels around England—really remarkable stuff for the 1530s, when his extensive journeying would have been extremely difficult, and sometimes perhaps even dangerous). He says of it that it had:

1. a crucifix at the head

2. an image of Arthur at the foot

3. a cross on the tomb

4. lions at the head and foot

5. two inscriptions, at least the first of which was written by Henry Swansey an abbot of Glastonbury

The first inscription reads:

“Hic jacet Arturus flos regum gloria regni

Quem mores probitas commendant laude perenni”

“Here lies Arthur the flower of kings, the glory of the kingdom,

Whom his character and uprightness commend for eternal praise.”

and the second, at the foot of the tomb says:

Arturi jacet hic conju[n]x tumulata secunda

Quae meruit coelos virtutum prole secunda”

“Here lies buried the second wife of Arthur,

Who has deserved Heaven from the fortunate offspring of [her] virtues.” (a wordplay—“secunda” can mean both “second” and “lucky”)

(my translations from John Leland, The Itinerary of John Leland, Parts I to III, edited by Lucy Toulmin Smith, 1907, page 288 and it’s right here for you: https://archive.org/details/itineraryjohnle02lelagoog/page/n11/mode/2up )

No “quondam” and no “futurus” here, either, and, presumably, this is the “tombe” which Mallory mentions. Did he make that inscription up? Certainly Mallory assembled a large body of previous work and not all of his sources are traceable. Perhaps this will remain a mystery, along with the reported disappearance and subsequent non-reappearance of Arthur?

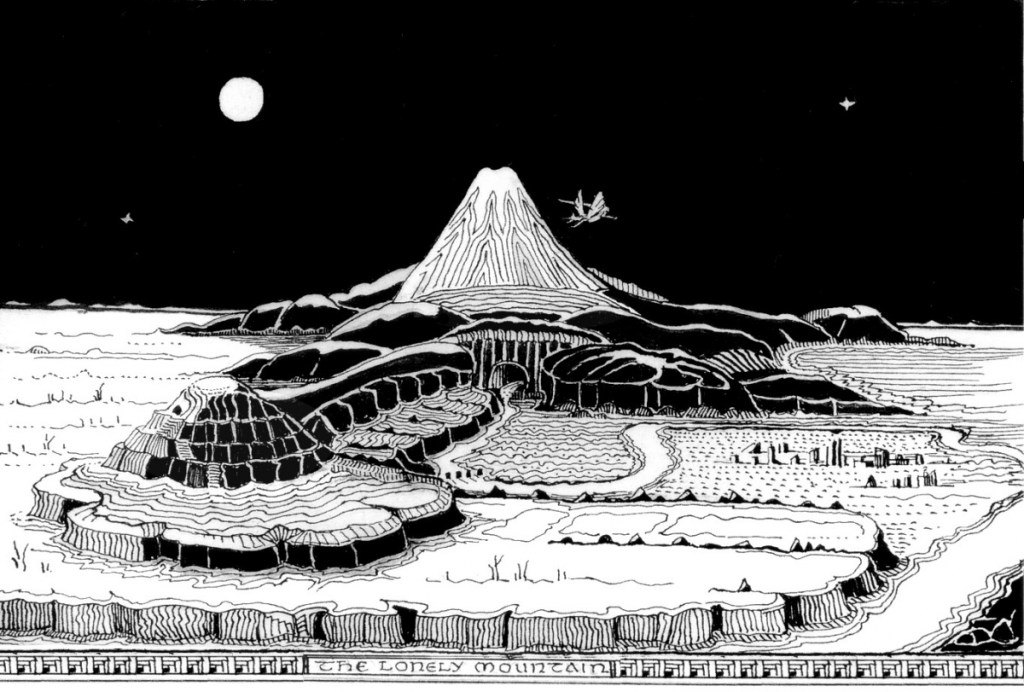

But the influence of Arthur, or, at least of his motif type, will appear in the second (and I hope fortunate) part of this posting. I’ll provide a hint here—someone once lived under another mountain before a new and destructive tenant arrived…

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

May you be both quondam and futurus/a,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O