As ever, dear readers, welcome.

In my last, in contrast to the previous two postings (on happy returns, or at least the expectation of them), I began discussing returns which were not quite as expected.

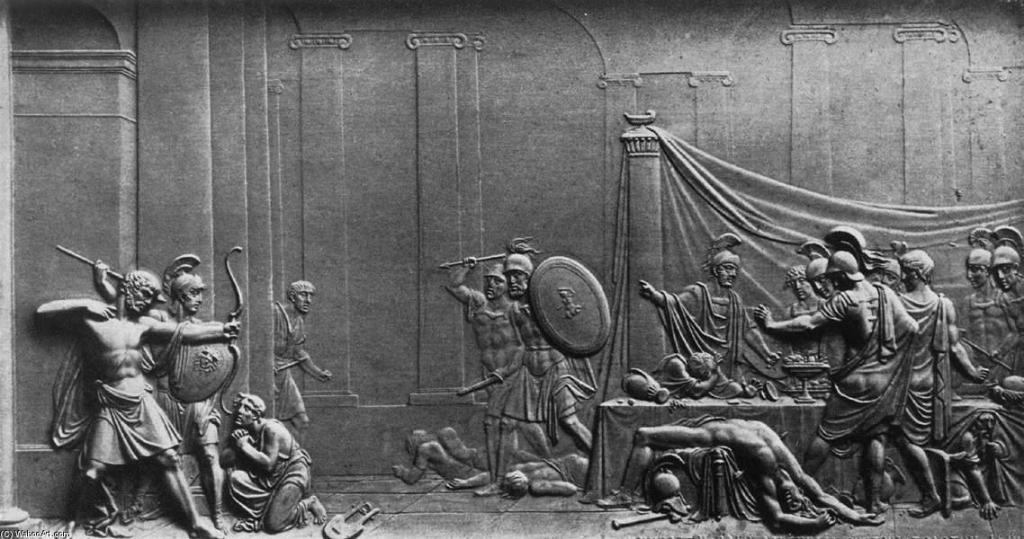

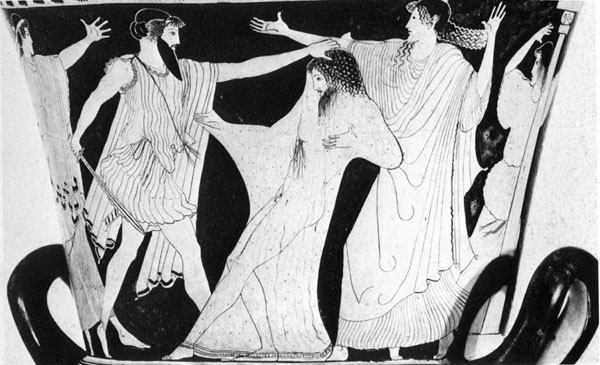

In that posting, I began with Agamemnon, who came home victorious from the Trojan War only to be murdered by his wife, Clytemnestra, and her BF and Agamemnon’s cousin, Aegisthus.

(In one version of the story, as seen here, killed when stepping out of his bath)

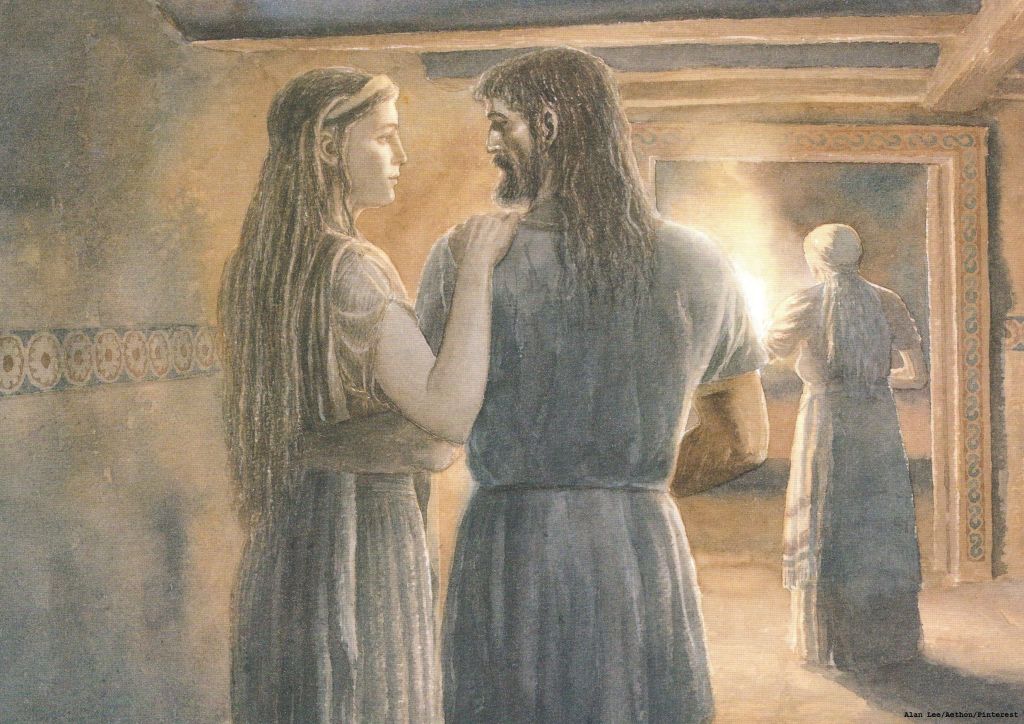

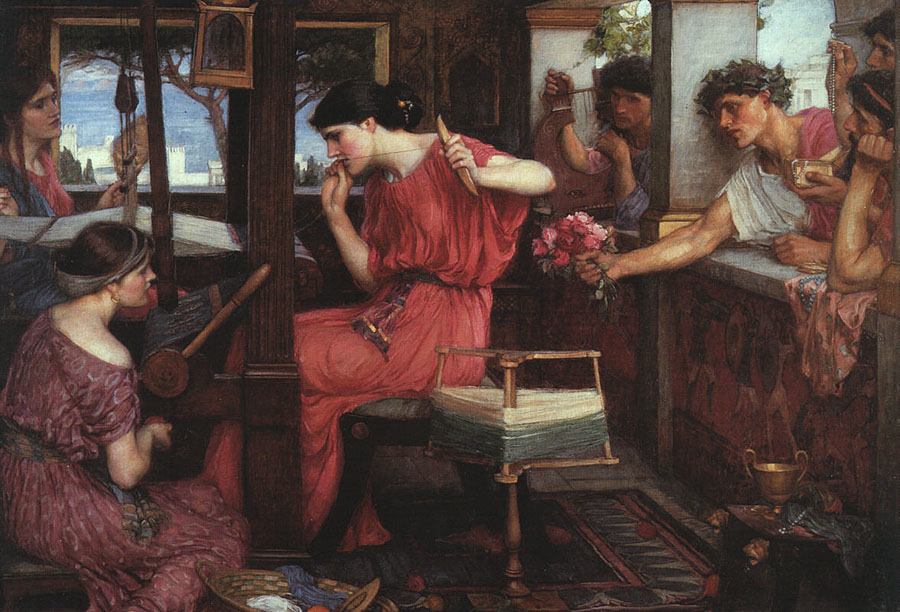

This is a fate which haunts the text I went on to next, the Odyssey, which I have just finished teaching. Over and over, Agamemnon’s betrayal and death are mentioned, each time seeming to point to what could be Odysseus’ fate, if his wife, Penelope,

pestered by over a hundred suitors, should prove as faithless as Clytemnestra. In the end, of course, she is faithful, those suitors meet a bloody end, and Odysseus and Penelope are happily reunited.

(Alan Lee—as good at Homer as he is at Tolkien!)

I had said, in that last posting, that I would move on in the next to what I’ll be teaching in the near future, The Hobbit, but, before that, I wanted to pause at another JRRT work, the title of which immediately suggests why: “The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm’s Son”, first published in 1953 in Volume 6 of Essays and Studies by Members of the English Association (New Series)—

which you can check out from the Internet Archive here: https://archive.org/details/essaysstudies1950000geof

This was republished in 1966 in The Tolkien Reader

and, in the 1975 edition of Tree and Leaf,

as well as in the 2023 The Battle of Maldon.

That title immediately links Tolkien’s work with an actual historical event, as well as an Old English poem about it.

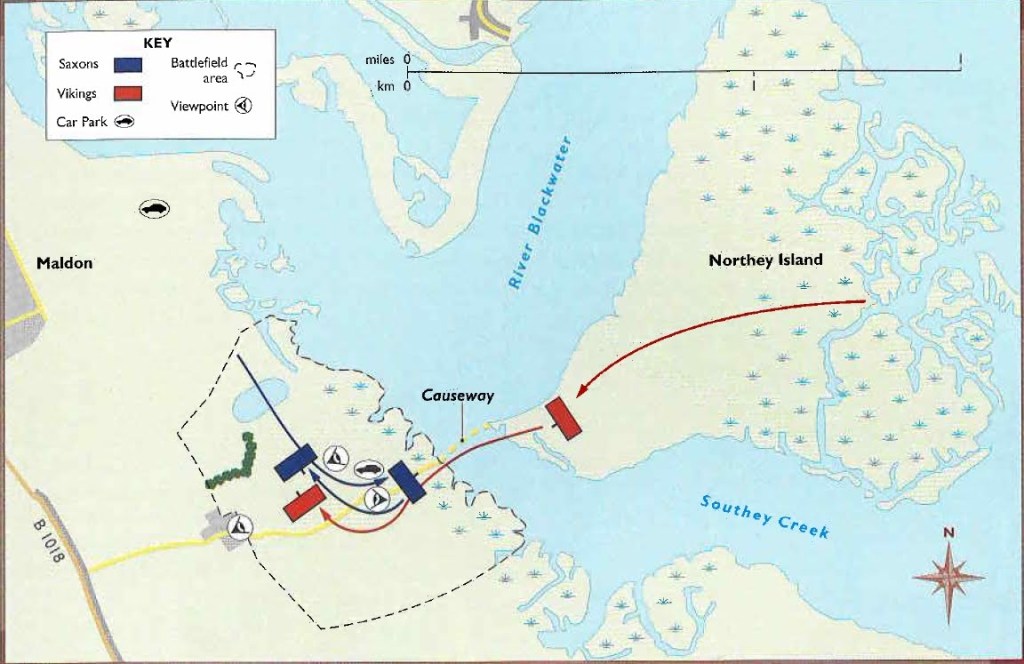

In 991AD, a Viking raiding force, which had been moving along the English coast, had paused on Northey Island, poised to attack the local town of Maldon.

Our main source for what happened next comes from that (fragmentary) Old English poem, “The Battle of Maldon”, a translation by Tolkien being included in that recent volume, along with “The Homecoming…”.

The Vikings were opposed by the local Anglo-Saxon leader, or ealdorman, Byrhtnoth (Beerht-nawth, approximately, where the “h” is like the “ch” in Bach—Tolkien uses an alternative spelling,). There was a landbridge between the island and the mainland at low tide

and, if we can believe the poem, the Vikings, initially repelled by the Anglo-Saxons under Byrhtnoth, then suggested that they be allowed to cross that landbridge to fight it out with their opponents on the mainland. Byrhtnoth accepts this proposal (there is a lot of scholarly discussion on why, including byTolkien, in an afterpiece called “Ofermod”), the Vikings cross, and, although the poem doesn’t tell us this, it appears , from other sources, that the ensuing battle ends with Byrhtnoth dead and his men driven from the battlefield, although the Vikings suffered heavily for their victory.

(by Peter Dennis, one of my favorite contemporary military artists)

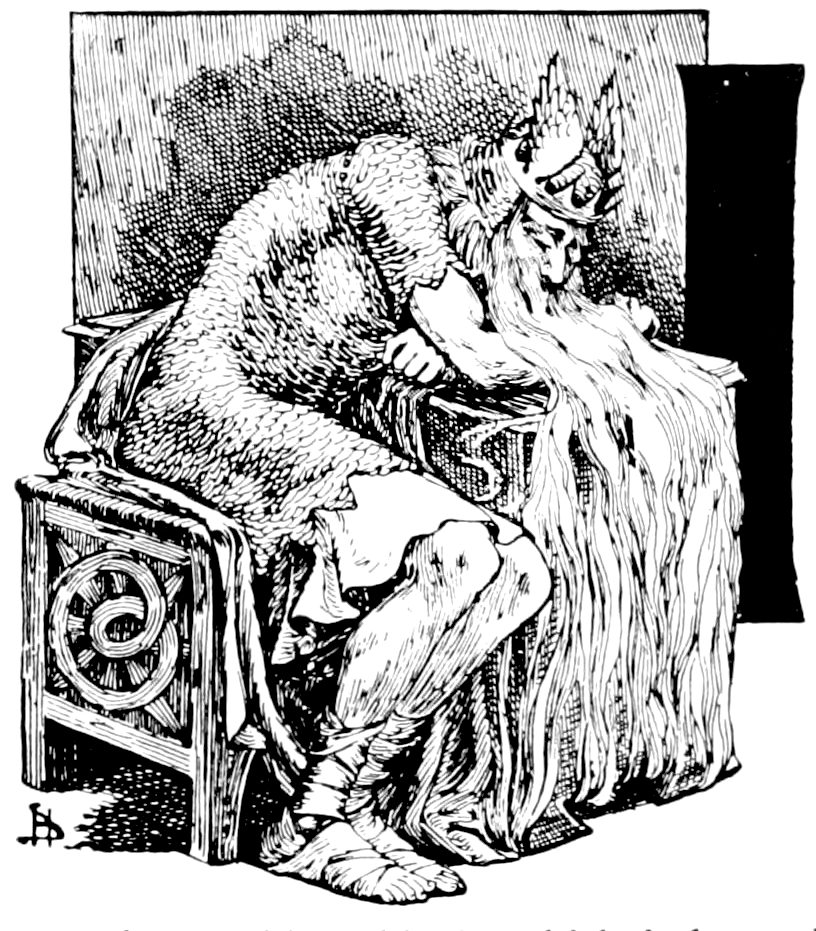

Tolkien’s “The Homecoming…” is a short verse play (the text suggests even a radio play) which is a dialogue between two characters, Tidwald (Tida) and Torhthelm (Tota), Anglo-Saxon servants of Byrhtnoth, who have come to the battlefield to collect his body. The verse is mostly of a loose alliterative kind, approximating Old English verse and, upon occasion, even using real Old English verse, as well as a number of mentions of its subjects. The themes of the play include a traditional one—searching a battlefield for a lost loved one—as well as a potential criticism of the ealdorman for agreeing to the Viking proposal and its consequences:

“Tidwald: …Alas, my friend, our lord was at fault…

Too proud! Too princely!”

(You can read about the poem “tThe Battle of Maldon” here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Battle_of_Maldon and read a translation here: https://oldenglishpoetry.camden.rutgers.edu/battle-of-maldon/ For the Old English, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ToAu_tyafp4 For a modern historical view of the battle see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x6Nqp-I1BIY For a Lego reenactment, which uses the poem itself as the narrative, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cbpc3nsJ3ec )

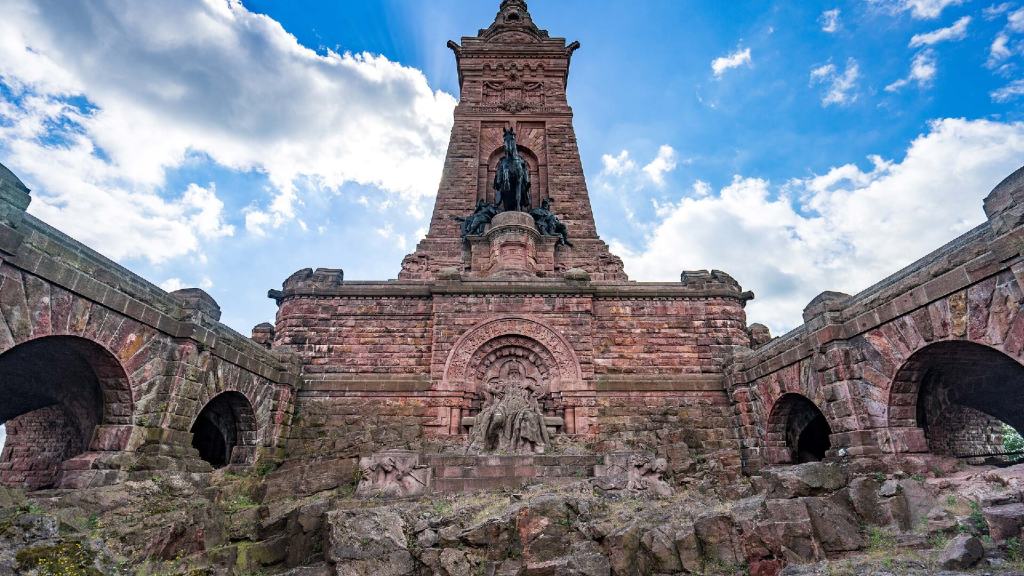

Byrhtnoth’s return was not a happy one, his body recovered, but headless, was taken to the religious establishment at Ely for burial—and reburial and reburial, as Ely became a major cathedral.

Here’s his latest tomb—

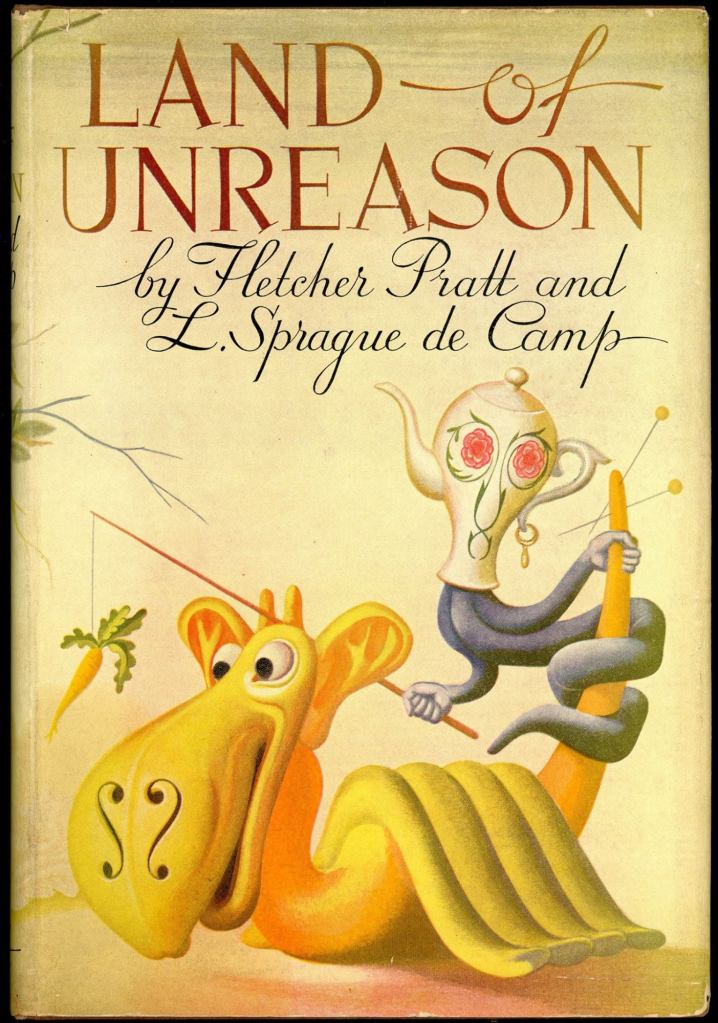

Bilbo’s anticipated return also had its darker moment.

From the beginning of the story, Bilbo had been pulled between the traits of his paternal and maternal inheritance. His father’s side (the Bagginses)—well, I’ll let JRRT tell you:

“The Bagginses had lived in the neighbourhood of The Hill for time out of mind, and people considered them very respectable, not only because most of them were rich, but also because they never had any adventures or did anything unexpected: you could tell what a Baggins would say on any question without the bother of asking him.”

His mother’s side (the Tooks) were of a very different order indeed:

“It was said (in other families) that long ago one of the Took ancestors must have taken a fairy wife. That was, of course, absurd, but certainly there was still something not entirely hobbitlike about them, and once in a while members of the Took-clan would go and have adventures. They discreetly disappeared, and the family hushed it up; but the fact remained that the Tooks were not as respectable as the Bagginses, though they were undoubtedly richer.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 1, “An Unexpected Party”)

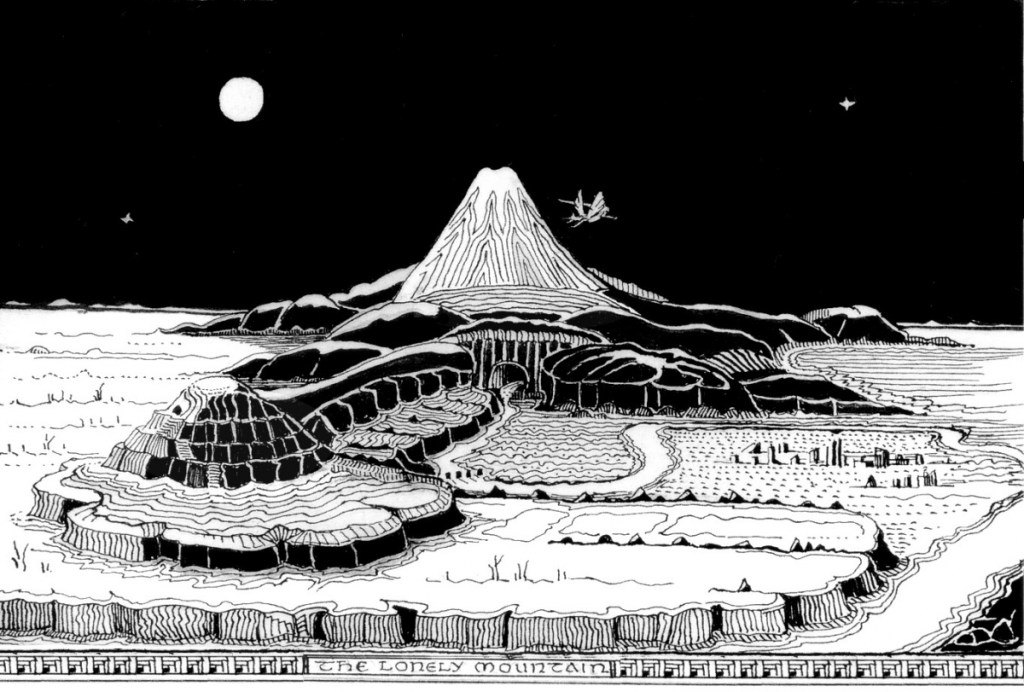

Throughout the novel, we see these two sides struggle for dominance, although, by the latter part of the book, t he Took side is clearly in control. After the Battle of the Five Armies, the death of Thorin, and return of the dwarves to the Lonely Mountain, however, he begins his journey home at last as

“The Tookish part was getting very tired, and the Baggins was daily getting stronger.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 18, “The Return Journey”)

But when Bilbo and Gandalf

”…came right back to Bilbo’s own door…There was a great commotion, and people of all sorts, respectable and unrespectable, were thick round the door, and many were going in and out—not even wiping their feet on the mat, as Bilbo noticed with annoyance.

If he was surprised, they were more surprised still. He had arrived back in the middle of an auction! There was a large notice in black and red hung on the gate, stating that on June the Twenty-second Messrs Grubb, Grubb, and Burrowes would sell by auction the effects of the late Bilbo Baggins Esquire, of Bag-End, Underhill, Hobbiton.”

Bilbo is put to some trouble in reestablishing himself in the Shire:

“It was quite a long time before Mr. Baggins was in fact admitted to be alive again…and in the end to save time Bilbo had to buy back quite a lot of his own furniture.”

This is, on the one hand, mildly comic—after so many death-defying adventures—trolls, goblins, wargs, Smaug—Bilbo has to prove to people who had known and seen him all his life that he was really himself and still alive? On the other hand, why might people be so ready to believe him dead after a single year? (The number of years differs significantly around the world—in Italy, it appears that 20 years must pass. See this for more: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legal_death )

Students always ask me about this. It’s an excellent question and the best answer I can offer at the moment is that Bilbo, on his return, has become a kind of Castor and Pollux.

In a complex ancient myth, these are twin brothers who share one immortality and one death, each alternating between the two, and perhaps we can see Bilbo, both Baggins and Took, as someone similar. As a Took, he was dead to his Baggins side, but, as a Baggins, it was the Took who died. In his return to the Shire, that transition might be signified by the question of his mortal status and also by the fact that, although

“…he was quite content; and the sound of the kettle on his hearth was ever after more musical than it had been even in the quiet days before the Unexpected Party…”

yet

“He took to writing poetry and visiting the elves…”

As Gandalf said, “My dear Bilbo!…Something is the matter with you! You are not the hobbit that you were.”

I want to conclude, however, with one more return and, from our viewpoint, one of the happiest, although, on a personal level , it began with misery. JRRT had been on the Western Front in time for the Battle of the Somme, in which one of his friends was killed on the first day, 1 July, 1916 (among nearly 60,000 other British casualties on that day alone), when Second Lieutenant J.R.R. Tolkien

became a casualty, on 27 October, 1916. It was not from a German bullet or shell, however, but from the bite of this–Pediculus humanus humanus—in plain terms, a louse–

This led to an intermittent fever, with all sorts of pains and complications for which a common name was “trench fever” (for more, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trench_fever ) and, effectively, it removed him from France and active participation in the Great War till its end, so that, although Tolkien was promoted to temporary Lt. 6 Jan 1918—see London Gazette (under 21 March, 1918 here: https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/30588/supplement/3561 ), he spent the rest of the war in England, happily resigning his commission in 1920 as this entry from the Gazette for 2 November, 1920 tells us:

“The undermentioned temp. Lts. relinquish their commissions on completion of service, 3 Nov. 1920, and retain the rank of Lt.: — J. R. .R. Tolkien…”

(for the complete entry, see: Page 10711 | Supplement 32110, 2 November 1920 | London Gazette | The Gazette )

And I would imagine that, even after his brief experience on the Western Front, Tolkien would agree with his Tidwald from “The Homecoming…”:

“Bitter taste has iron, and the bite of swords

Is cruel and cold, when you come to it.”

and be glad to be done with it and home.

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

May your returns always be happy ones,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

And, next week, HALLOWEEN!