As always, welcome, dear readers.

Spelling, in English, which can cause non-native English-speakers to wonder just how crazy we are, began to become standardized only in the 18th century. Before this, one might, for example, see two competing spellings of the main word in the title of this piece: “Compleat” and “Complete”, both considered valid, at least by the spellers.

Although the spelling “compleat” might have been commonly acceptable in the 17th century, it is one work, in particular, which has continued to provide us with that competing spelling, Izaak Walton’s (1593-1683)

well-known fishing manual, The Compleat Angler,

first published in 1653, with various later editions, including one with an extensive addition, in 1676, by Walton’s friend, and fellow-angler, Charles Cotton (1630-1687),

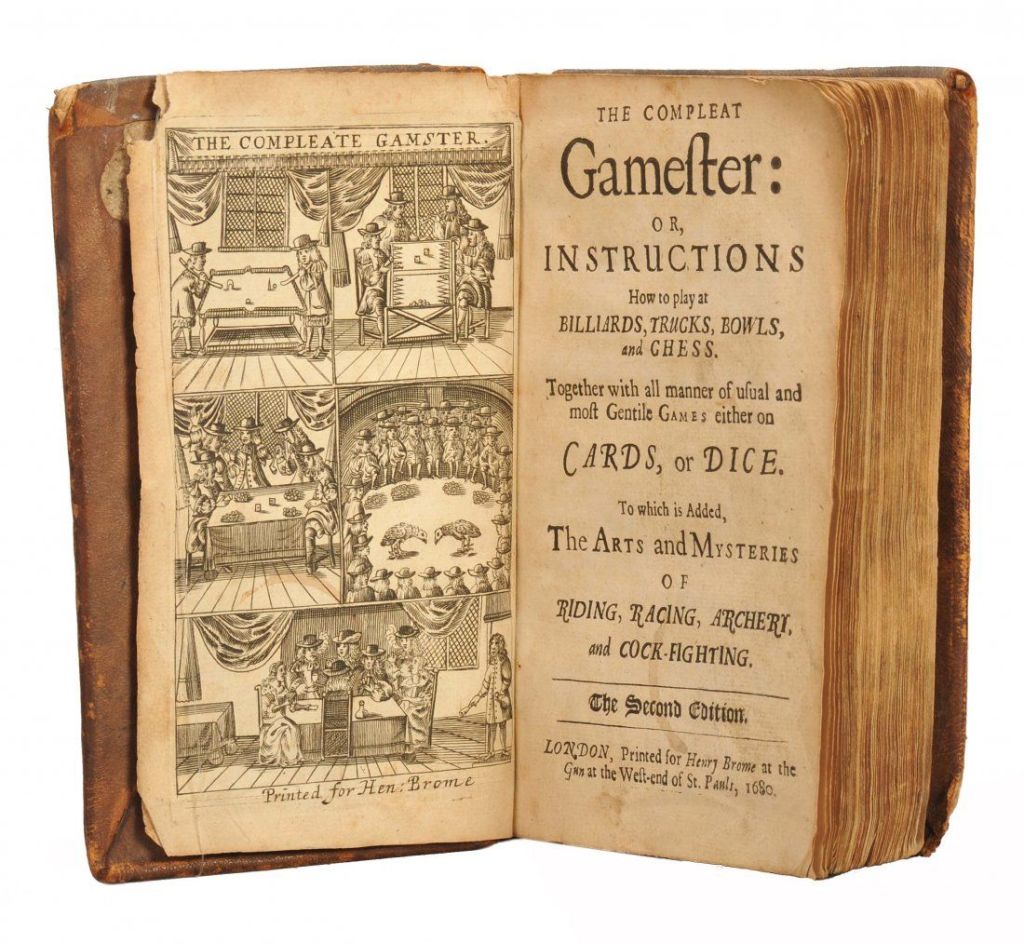

to whom was attributed, in the 18th century, another “Compleat”, The Compleat Gamester (1674).

(This is the 1680 edition. If you’d like to learn how to play such card games as “Lanterloo” and “Bragg”, here’s the 1725 edtiion to show you the way: https://ia902708.us.archive.org/6/items/bim_eighteenth-century_the-compleat-gamester-o_cotton-charles_1725/bim_eighteenth-century_the-compleat-gamester-o_cotton-charles_1725.pdf For myself, the cockfighting is distasteful and I’d avoid it. For the Walton/Cotton, here’s a wonderfully leisurely 1897 edition, heavily illustrated with handsome engravings, and based upon that 1676 edition: https://archive.org/details/compleatangler00gallgoog/page/24/mode/2up One of my favorite illustrators, Arthur Rackham, made an illustrated edition, but, as it’s from 1931, it’s still locked in copyright, but you can see images from it if you write in: “Compleat Angler Rackham”.)

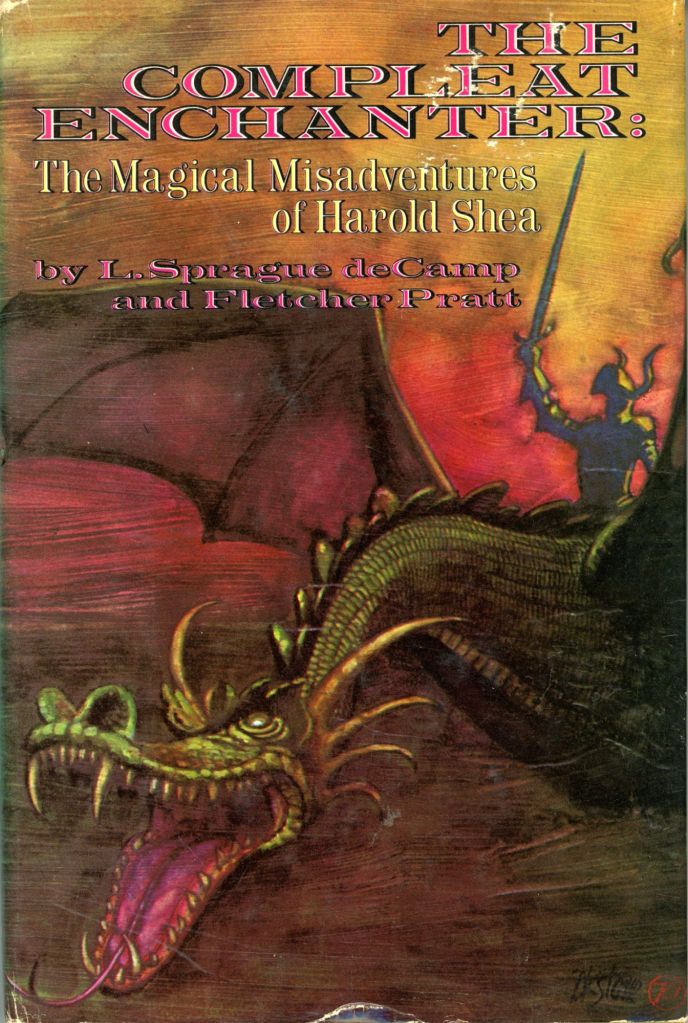

I most recently happened upon this spelling in a completely/compleatly different context:

This is a collection of short novels or novellas jointly written by L(yon) Sprague de Camp (1907-2000)

and Fletcher Pratt (1897-1956),

2 prolific fantasy/science fiction authors of the mid-to later 20th century. (For a very partial list of de Camp’s works, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L._Sprague_de_Camp ; for the same for Pratt—who also wrote a number of historical works—see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fletcher_Pratt )

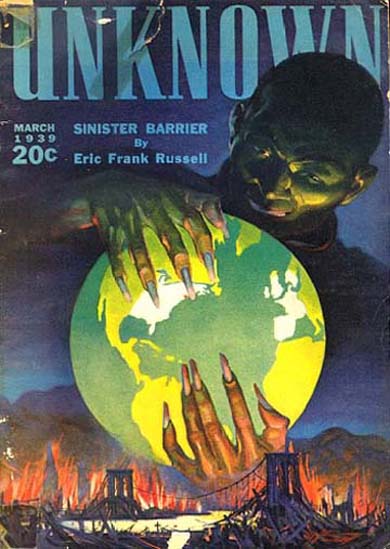

Although there are three novellas in this collection, “The Roaring Trumpet”, “The Mathematics of Magic”, and “The Castle of Iron”, there is a fourth, published as “Wall of Serpents”. And these were not their original publication—or forms—as all had been previously published in fantasy/science fiction magazines of the 1940s and early 1950s, like Unknown (about which you can read a wonderfully detailed account here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unknown_(magazine) ).

In these stories, the main character, Harold Shea, a psychologist by training, travels, with various colleagues, to a series of worlds based upon mythology and literary sources, “The Roaring Trumpet” upon Norse legends,

(the original cover of Unknown where the story first appeared)

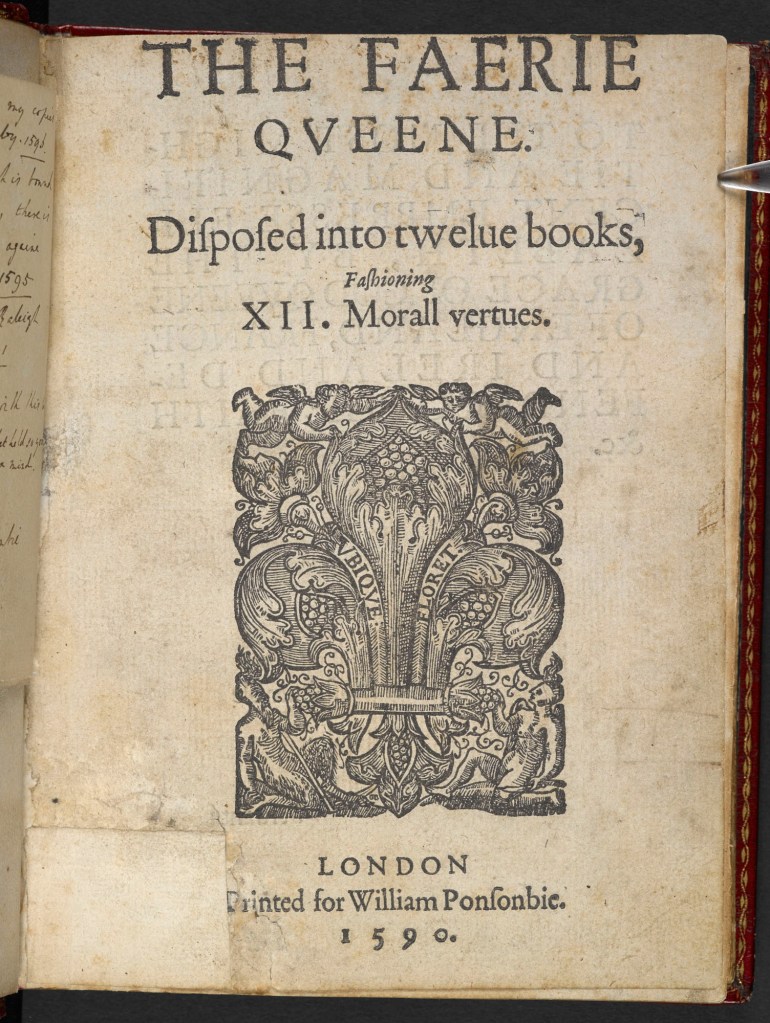

“The Mathematics of Magic”, in which the characters fall into the world of Edmund Spenser’s (1552-1599)

The Fairy Queen,

“The Castle of Iron” into the world of Ludovico Ariosto’s (1474-1533)

Orlando Furioso

(originally published in 1532, this is an early edition from 1562)

and Wall of Serpents, into the land of Finnish myth from Elias Loenrot’s (1802-1884)

Kalevala,

(This is the more complete edition of 1849, Loenrot had published an earlier version in 1835.)

but, in mid-book, the main characters are suddenly transported from ancient Finland to ancient Ireland, where they spend time with characters out of the Ulster Cycle, the main charmer being the hero Cu Chulainn.

(This is actually a rather subdued portrait of “the Hound of Ulster”, most of those I’ve seen have absolutely no relation to the figure we know from Old Irish Literature. If you’re interested, you might try Lady Gregory’s Cuchulain of Muirthemne, 1903, here: https://archive.org/details/cuchulainofmuirt00greg_0 bearing in the mind that Lady G was a late-Victorian and the original stories can be a bit raunchier than she will translate them. )

Although the original editor, John W. Campbell, as we learn from the article on Unknown cited above, wanted “the fantasy elements in a story to be developed logically”, I confess that I have no idea as to how the characters are transferred to these places. The theory behind the transference is discussed in “The Roaring Trumpet” , but my eyes crossed when I tried to follow it. The method is really quite beside the point, however, as, once the characters are dropped into each world, the narrative roars by, and, although there are in-jokes, if you know the originals (parts of Wall of Serpents, for example, are written in the same metre as the original Finnish text), the stories are solid enough in themselves to be enjoyable without doing anything more than following along. (If you’d like to read them—and I would encourage you to—you can read the first three by joining the Internet Archive and borrowing a copy of The Compleat Enchanter here: https://archive.org/details/compleatenchante00deca )

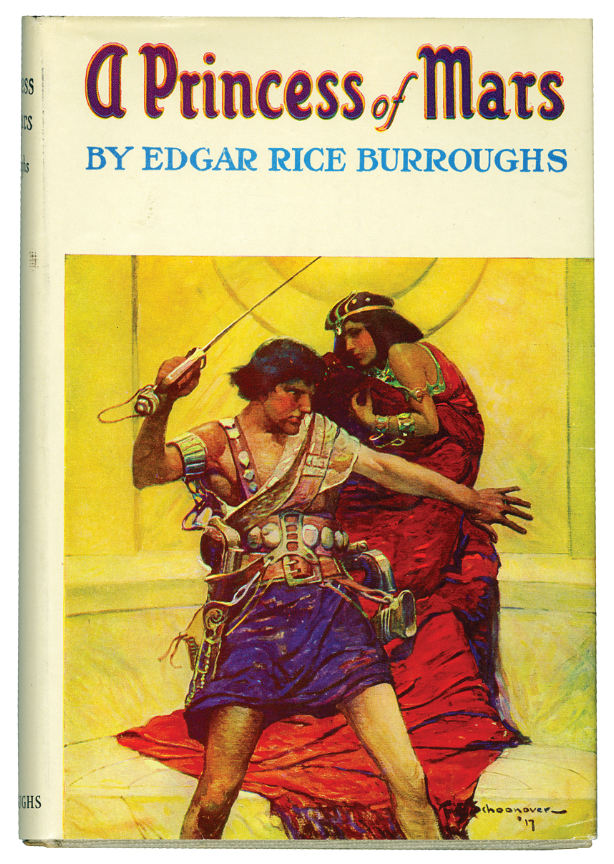

The title of this piece is “Incompleat”, however, and refers, in fact, to a larger project I’ve set myself. Although I’ve read a certain amount of fantasy and science fiction, I’ve never done this systematically. Consequently, I decided to give myself a better education, beginning with science fiction, compiling a list of books, novellas, and short stories in chronological order which I intend to read. I admit to doing a bit of skipping around as I fill things in, so I still have to read Jules Verne’s De la Terre a la Lune (“From the Earth to the Moon”, 1865, first English translation, 1867), for example, but I’d gotten caught by de Camp/Pratt after reading earlier things like Edgar Rice Burrough’s (1875-1950) A Princess of Mars (1912/17, which you can read here: https://archive.org/details/aprincessmars00burrgoog/page/n9/mode/2up ),

about which I’m definitely going to write in the future. The field is vast (and fantasy is just as large—go to any decent bookstore and look at the shelves and shelves of the stuff), so I want to be selective, trying to find what’s most representative of different eras and trends. This will mean that I’ll definitely wind up with some less than masterpieces, but it’s important, to understand the field, to see just what has been considered noteworthy in the past.

I doubt that I’ll ever write a posting with the title “Compleat”, but I’m sure to find much that’s worth the read and, when I do, I’ll be glad to pass it on to you.

Stay well,

Beware any enchanter who claims compleatness,

And remember that there’s always

MTCIDC

O

PS

And, if you read this blog for Tolkien, not to worry—he’s always there and always will be. After all, he himself was a fan of the work of Isaac Asimov.