Welcome, as always, dear readers.

I was reminded of my last posting by seeing this on the back bumper of a car—

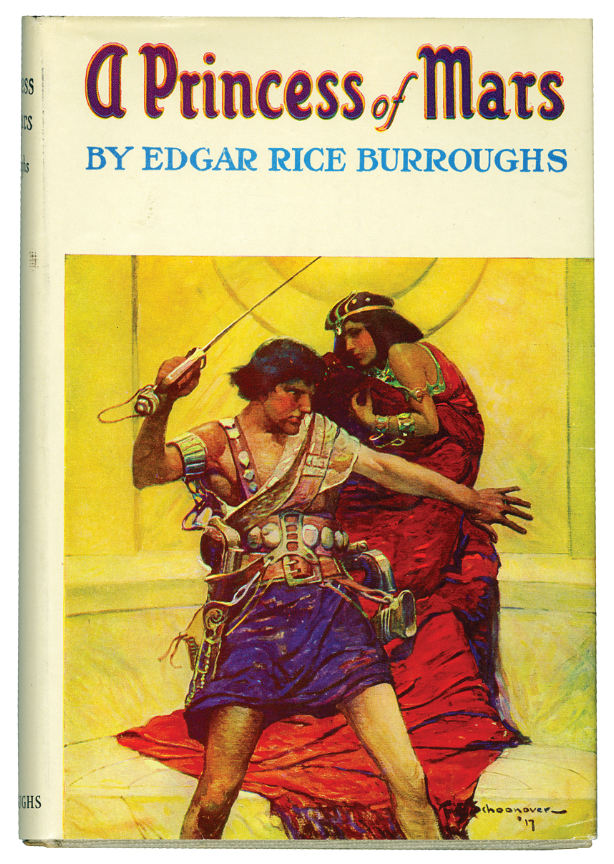

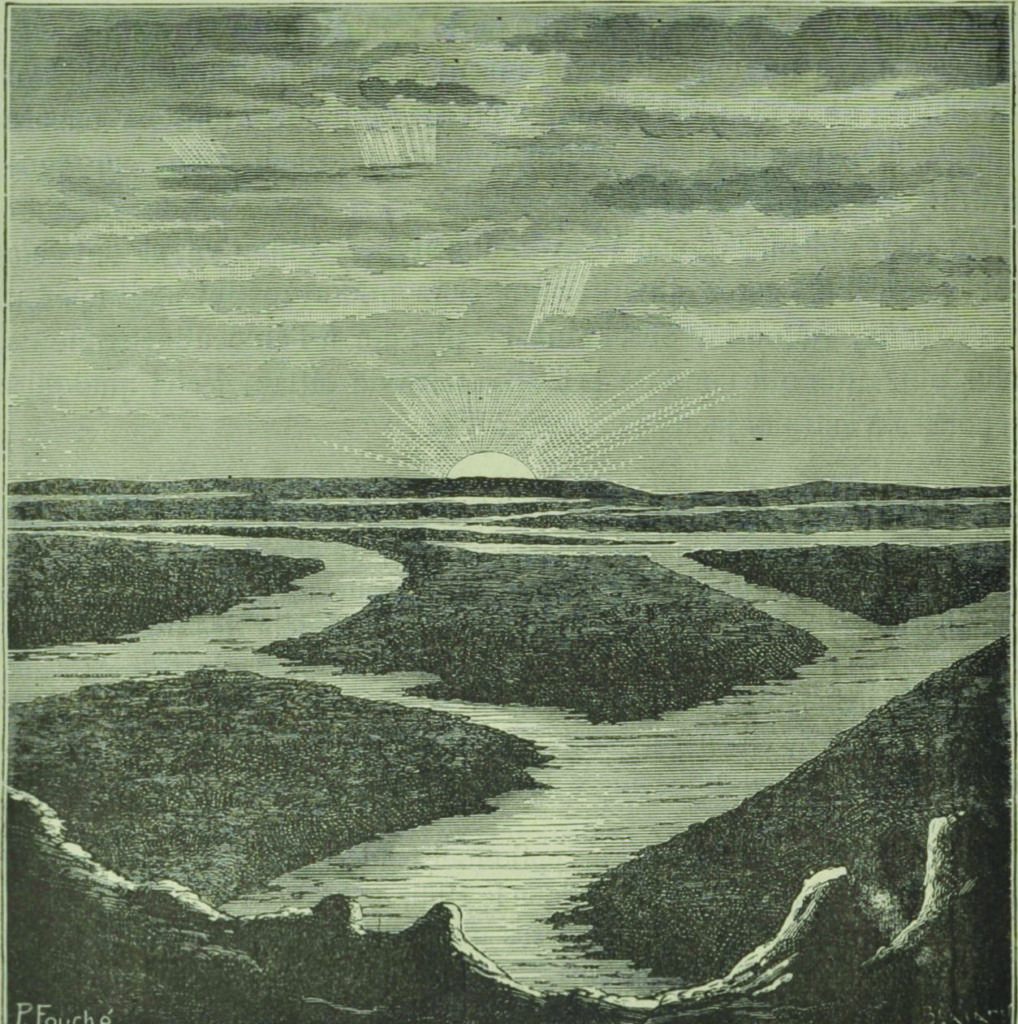

Mars to me is this—

and this—

which hardly makes it look worth busting for, or even visiting, for all of the scientific curiosity about it which could be satisfied by extensive exploration, if not colonization.

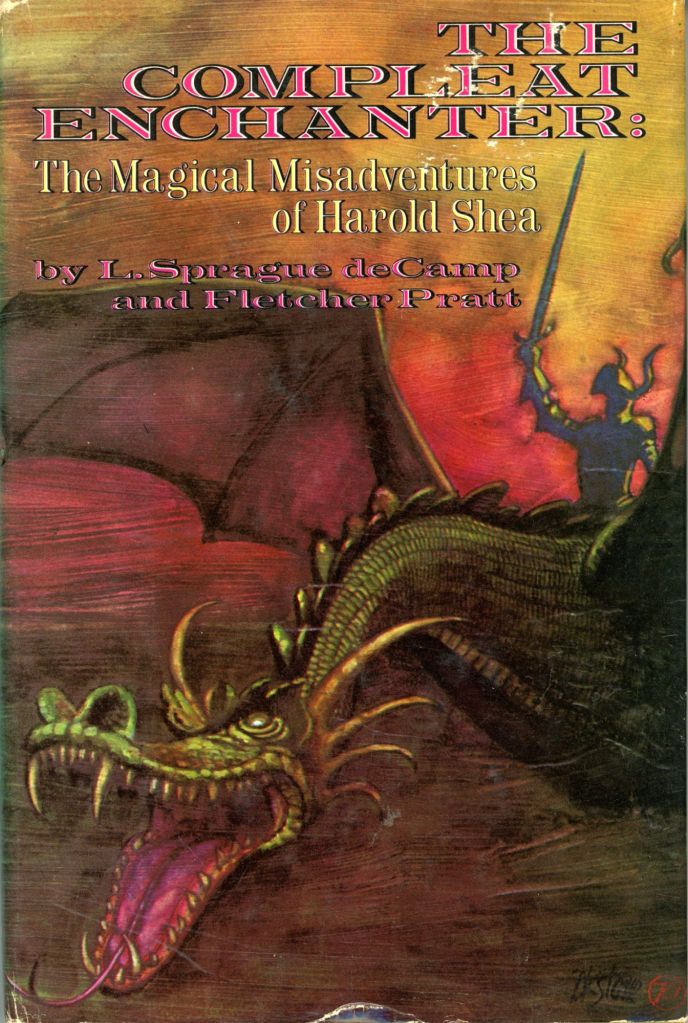

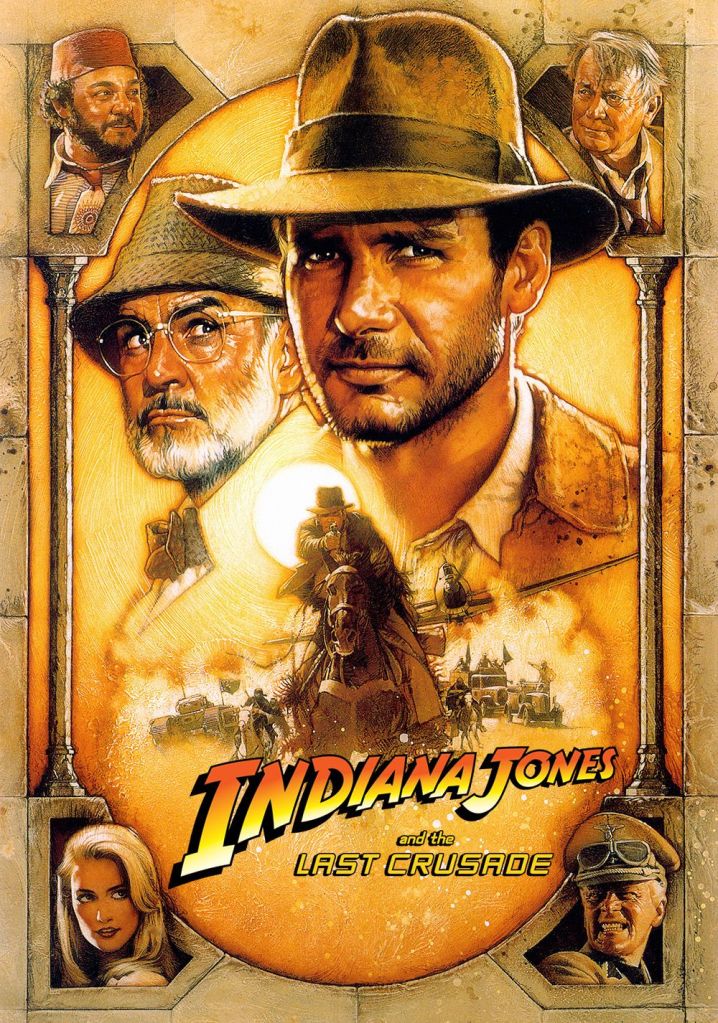

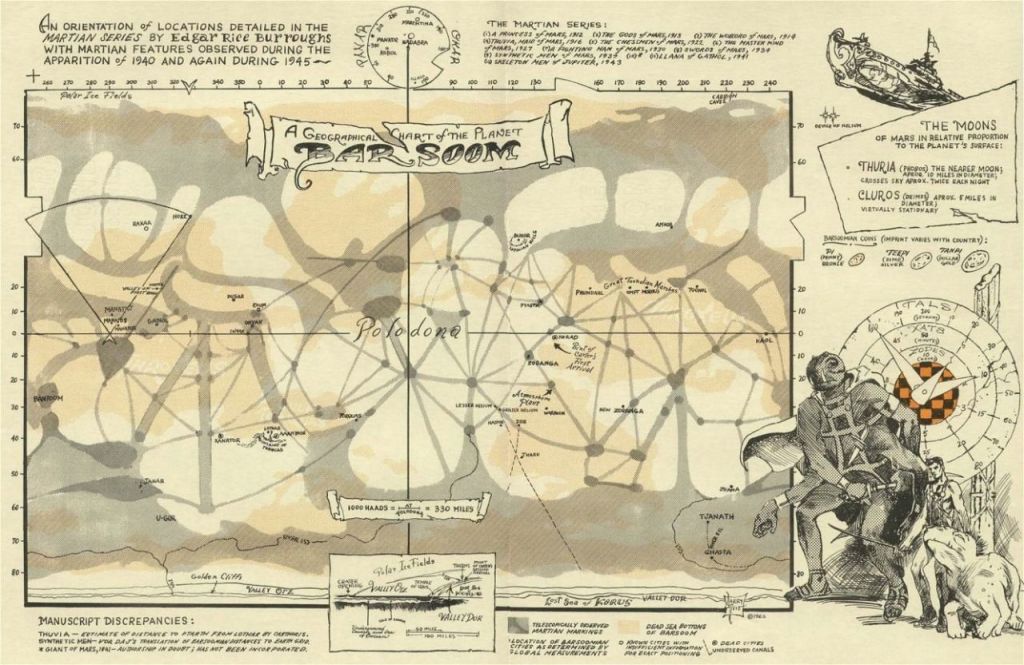

Suppose, however, it looked like this—

or this—

(This is from https://www.erbzine.com/mag33/3387.html a fan magazine devoted to the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs—about whom more shortly!)

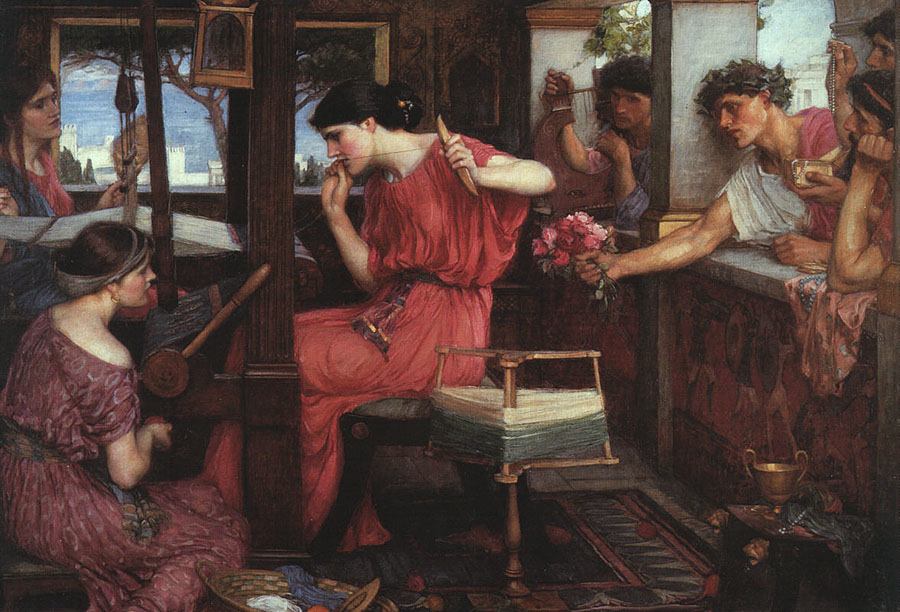

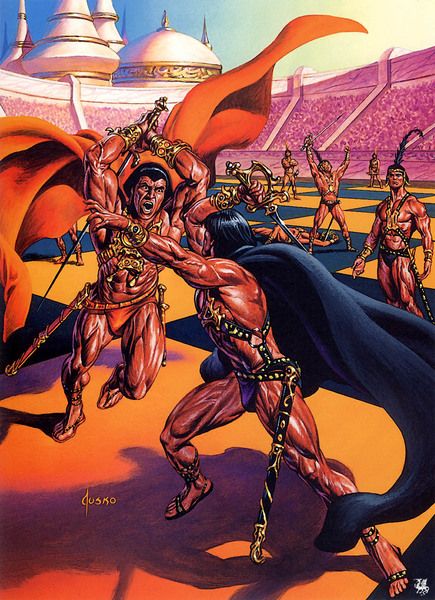

or this—

(Joe Jusko—you can visit his website here: http://www.joejusko.com/default.asp )

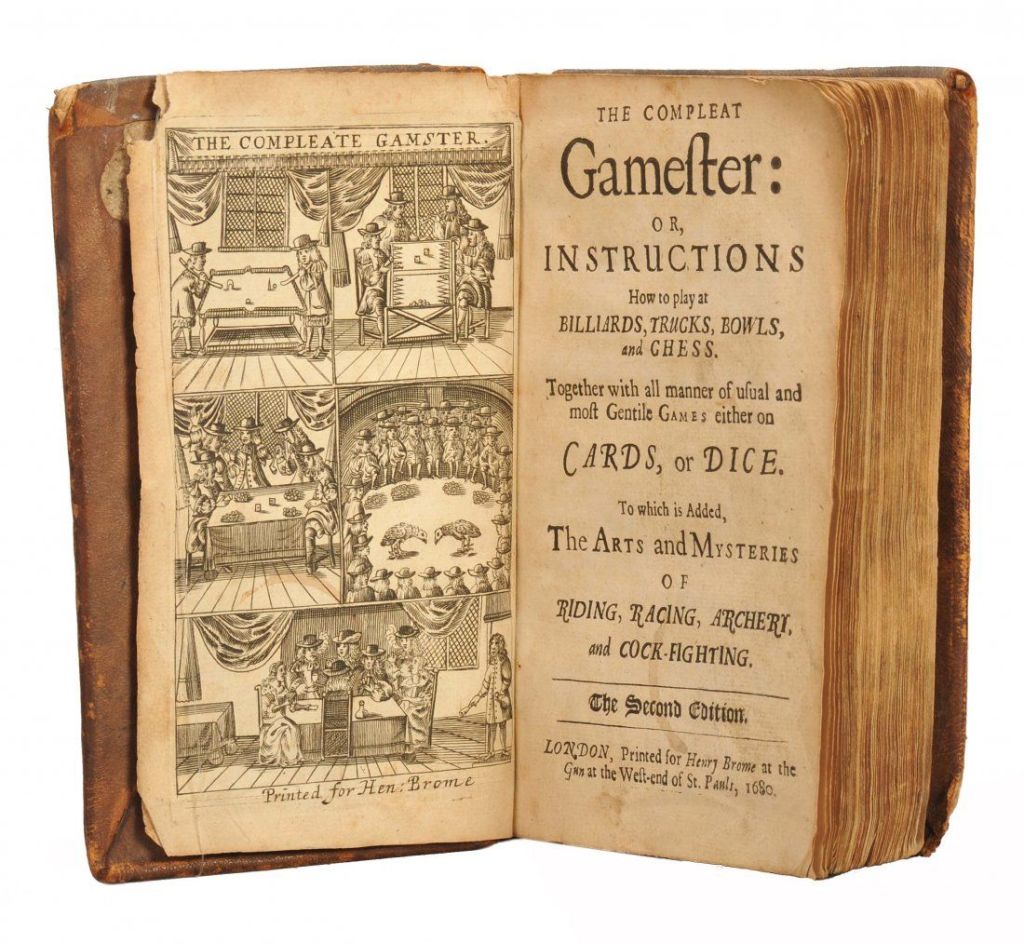

Beginning in the 1870s, these latter views were the basis of science—and science fiction.

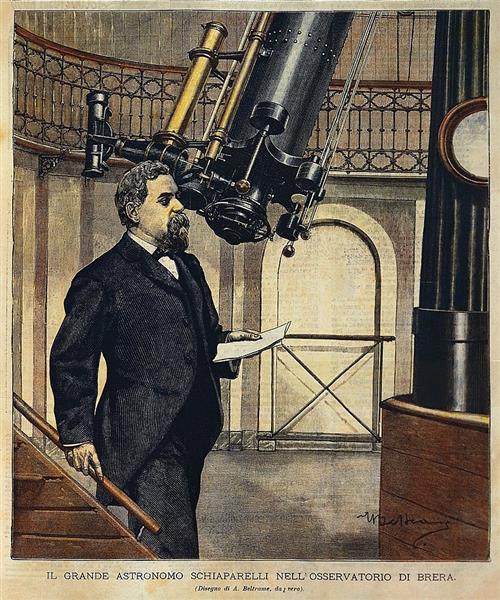

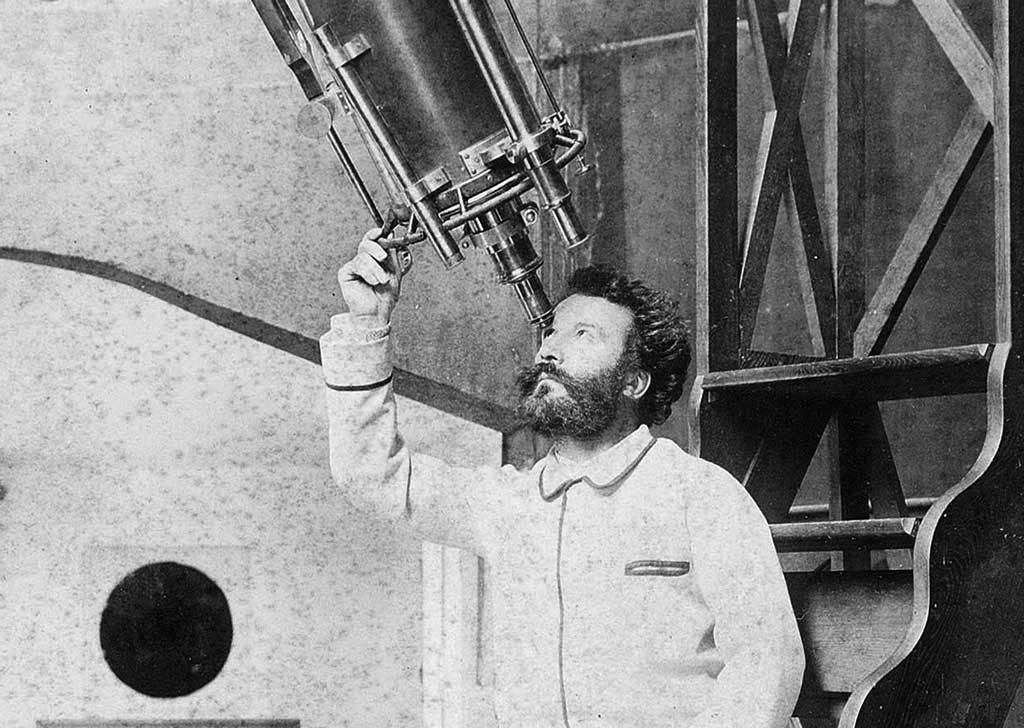

The first figure to put forward such a view of Mars was Giovanni Schiaparelli (1835-1910),

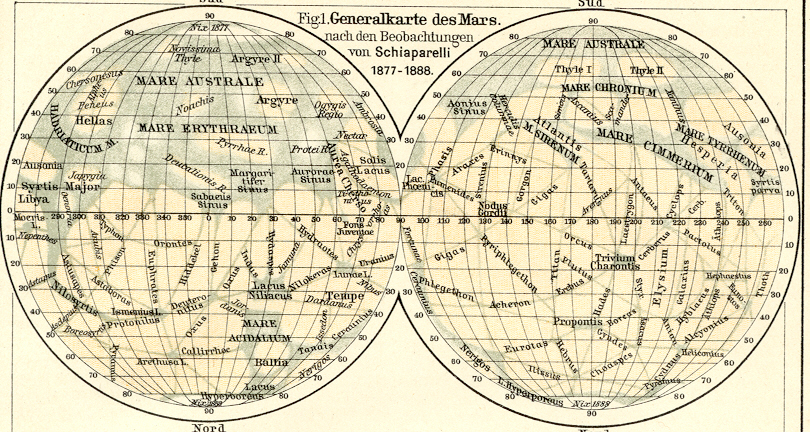

who, turning his telescope towards the Red Planet, believed that he saw patterns of crisscross lines across its surface, which he called canali, in Italian, and which can mean everything from the anatomical “duct” to (now) a television channel, to “canal” (as in i canali di Venezia),in an 1877 publication.

It’s important here to note that Schiaparelli was no crackpot, but a well-known and well-respected astronomer, and this will be true for the prominent men who furthered the idea that Mars was inhabited by sentient beings with engineering and architectural skills. The texts which such men wrote are carefully-reasoned, based on the latest science known to them. The basic problem was that Schiaparelli hadn’t seen canals at all, even as he produced maps of Mars’ surface which included them

and wrote articles about the potential inhabitants (see https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/7781/pg7781.html La Vita sul Pianeta Marte, extracts from the journal “Natura ed Arte” from 1893, 1895, 1909 ) in scientific journals.

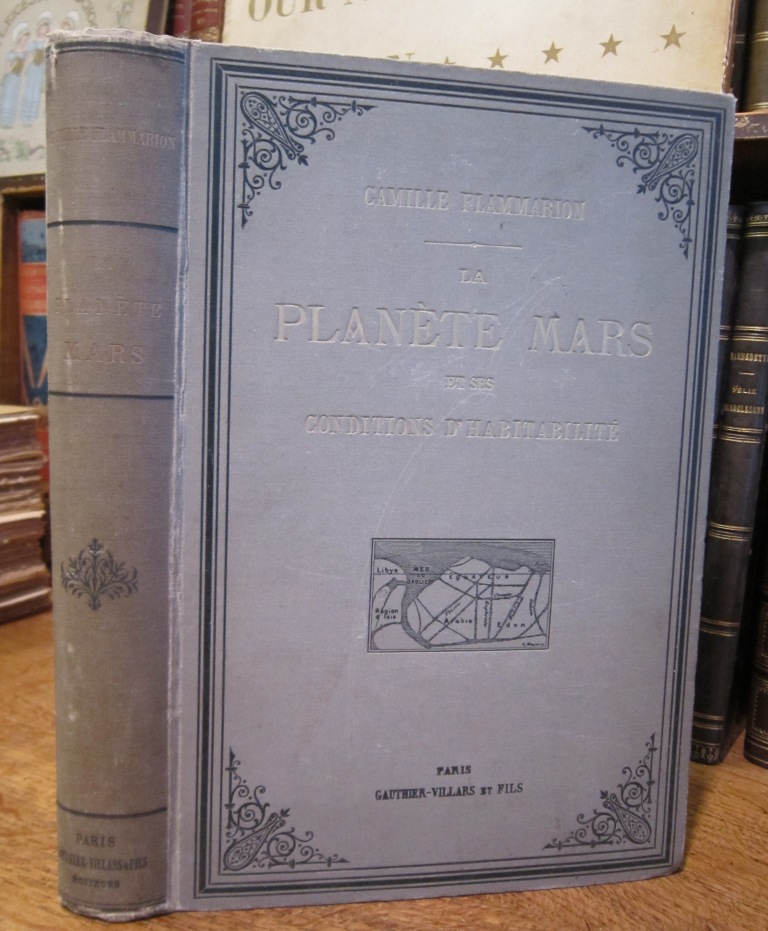

He was followed by the splendidly-named Camille Flammarion (1842-1925),

another prominent astronomer and the author of numerous books on the subject, including

La planete Mars et ses conditions d’habitabilite (1892) and which is available here: https://archive.org/details/laplantemarset01flam For a complete translation into English of this work, log in to the Internet Archive and take out the Patrick Moore version here: https://archive.org/details/camilleflammario0000flam For a brief review of Flammarion’s ideas in English, see: https://ia903207.us.archive.org/33/items/jstor-25118640/25118640.pdf The North American Review, 1 May, 1896, 546-557, “Mars and Its Inhabitants” .

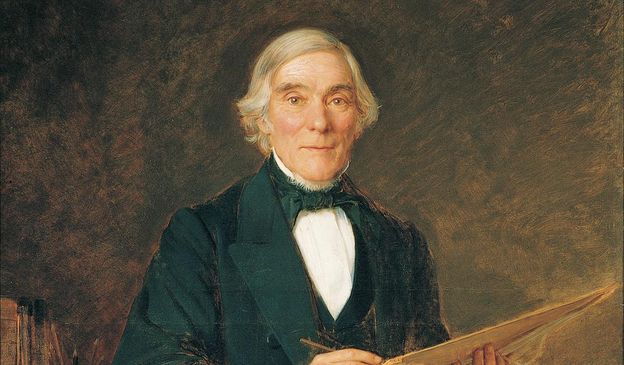

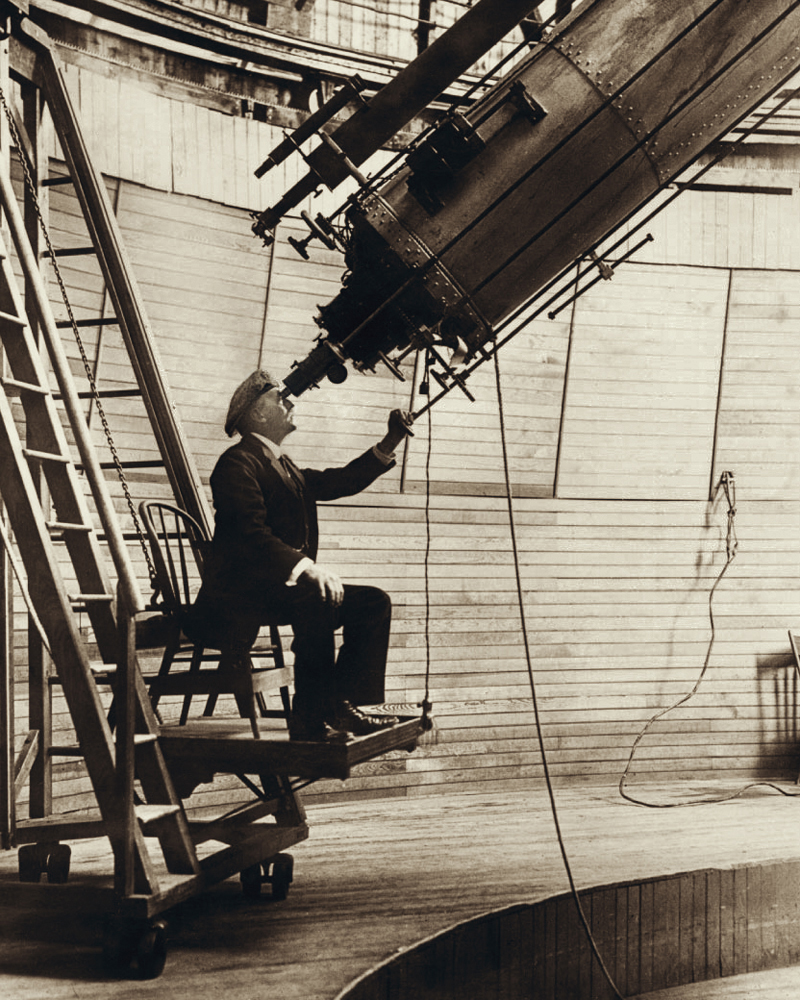

For English-speakers, the scientist who probably had the greatest effect upon popular views of Mars was Percival Lowell (1855-1916),

who, besides lectures and scholarly articles, produced three extensive works on the subject: Mars (1895—available here: https://archive.org/details/mars01lowegoog/page/n12/mode/2up ), Mars and Its Canals (1906—dedicated to Schiaparelli and available here: https://archive.org/details/marsanditscanals00loweiala/mode/2up ), and Mars As the Abode of Life (1908 and available here: https://archive.org/details/marsasabodelife03lowegoog/mode/2up ).

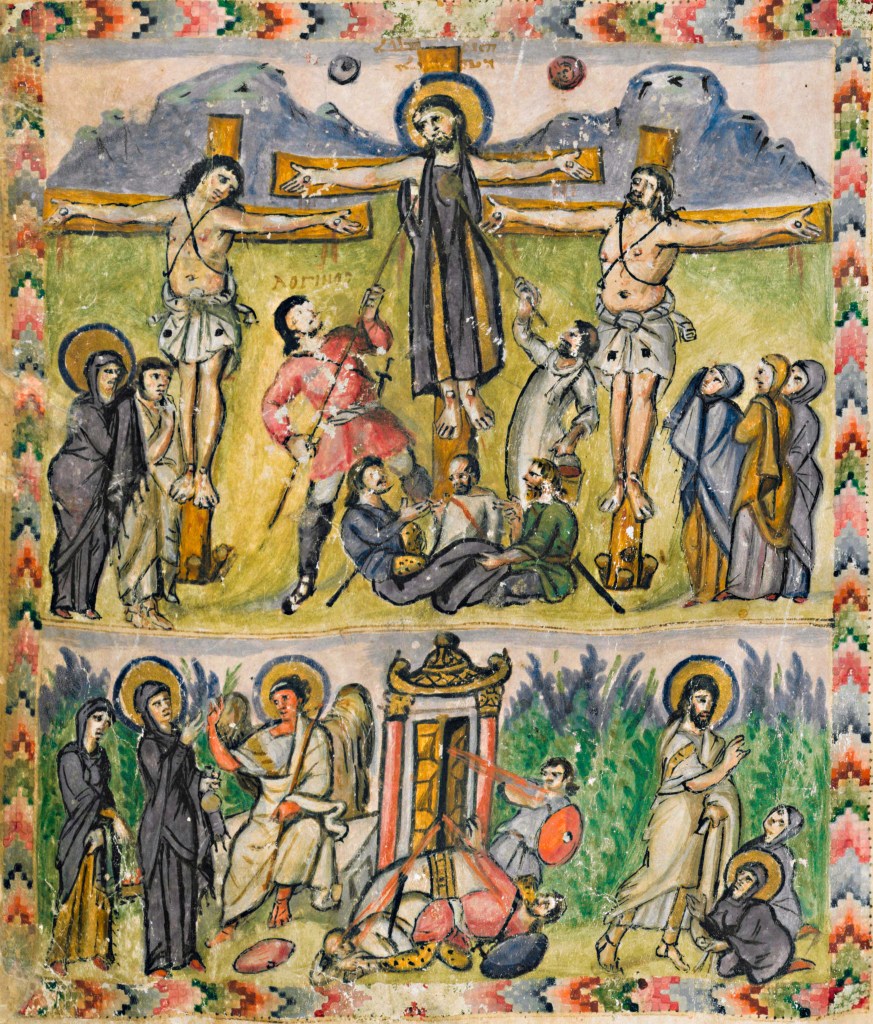

What I find particularly interesting about the approach over time to the subject of Mars, its inhabitants, and its architecture is that this was believed to be an archaic civilization and may even be in serious decline, a fact which was picked up—among other details–by a man who was about to make his name by basing a series of fictional works upon the scientific research and publications of such scientists, Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875-1950).

In February, 1912, Burroughs published the first of six installments of a series entitled “Under the Moons of Mars” in The All-Story (and which you can read here: https://archive.org/details/all-story-v-022n-02-1912-02-ifc-ibc-ufikus-dpp )

It concerns the adventures of John Carter, an ex-Confederate, who after the war, turns prospector in the American Southwest, only to be mysteriously whisked to what he in time discovers is called “Barsoom”, but is based upon the Mars of the Victorian/Edwardian astronomers, dying civilization, canals, and all.

It has two main races, a more human one, who were the city-builders, and a larger and more barbaric humanoid green-skinned race, who are nomads, but who inhabit the deserted human cities during their wanderings.

(by Adam C. Moore, a wonderfully-talented artist who can seemingly draw anything and who goes by LAEMEUR—visit his website at: https://laemeur.com/illustration/ )

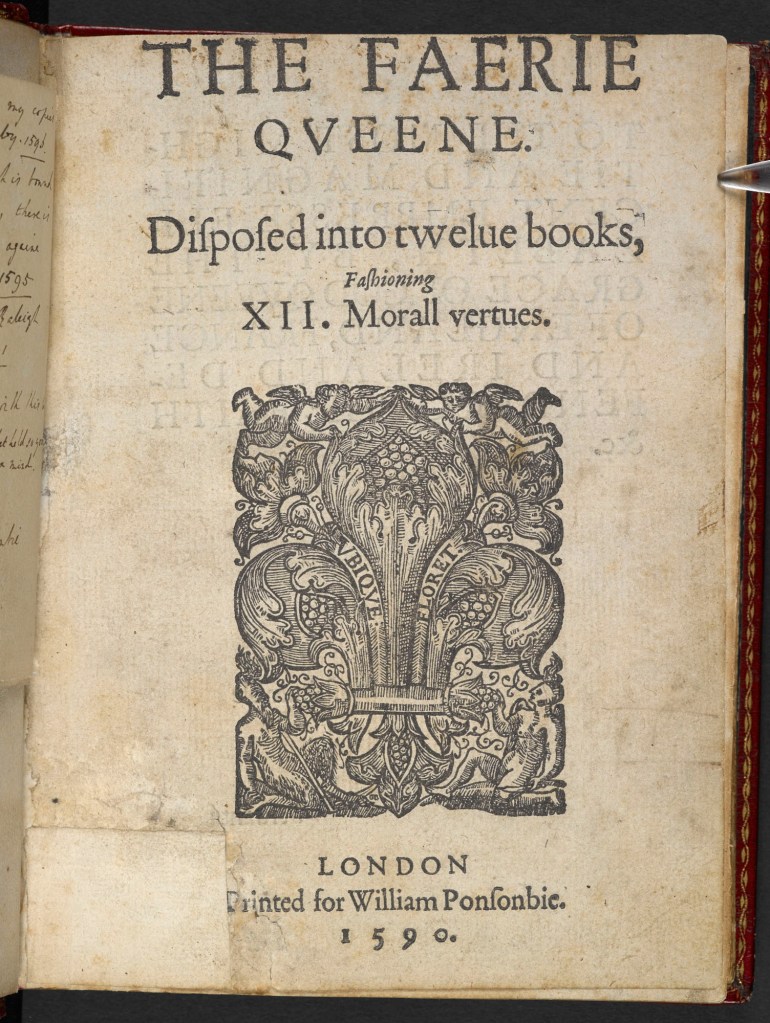

Although I’ve always known that Burroughs was an early science fiction, fantasy writer, I hadn’t read a word of his work until, in my current slow study of science fiction, I added “Under the Moons of Mars” in its 1917 novel form, A Princess of Mars, to my reading list (and you can add it to your list here: https://archive.org/details/aprincessmars00burrgoog/page/n9/mode/2up )

It didn’t take more than a chapter or two before I found myself with a page-turner. Although the characters are familiar from any high adventure novel—the man of his hands dropped into a new and strange situation, the proud princess in need of rescue, etc—Burroughs, for me, had set these against a backdrop which, though based upon period popular scientific thought, he made his own by taking what he’d found and expanding it into something more dynamic, both in setting and in the politics and conflicts of what might be a dying world.

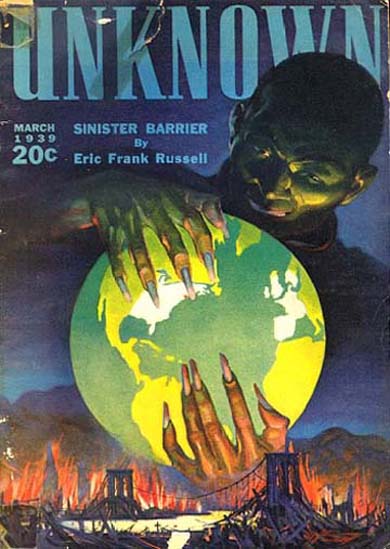

So far, I’ve only read the first book, but there are 9 more stories in novel form to come, from 1918 (The Gods of Mars) to 1948 (Llana of Gathol—for a listing, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barsoom ) to look forward to and Burroughs wrote other series, including one which he began publishing in the same year and in the same magazine as “Under the Moons of Mars” and which probably brought him more fame and wealth than the adventures of John Carter—

(This is also from the Burroughs website which, if Burrough’s work interests you, and you don’t know the site, I encourage you to visit and browse its extensive archive.)

As ever, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

If dropped onto another planet, hope that its gravity is lighter,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O