As always, welcome, dear readers.

In his own field, Tolkien was, not surprisingly, a very well-read scholar, and, in certain areas beyond his field, like Celtic Studies, he was informed, if not expert.

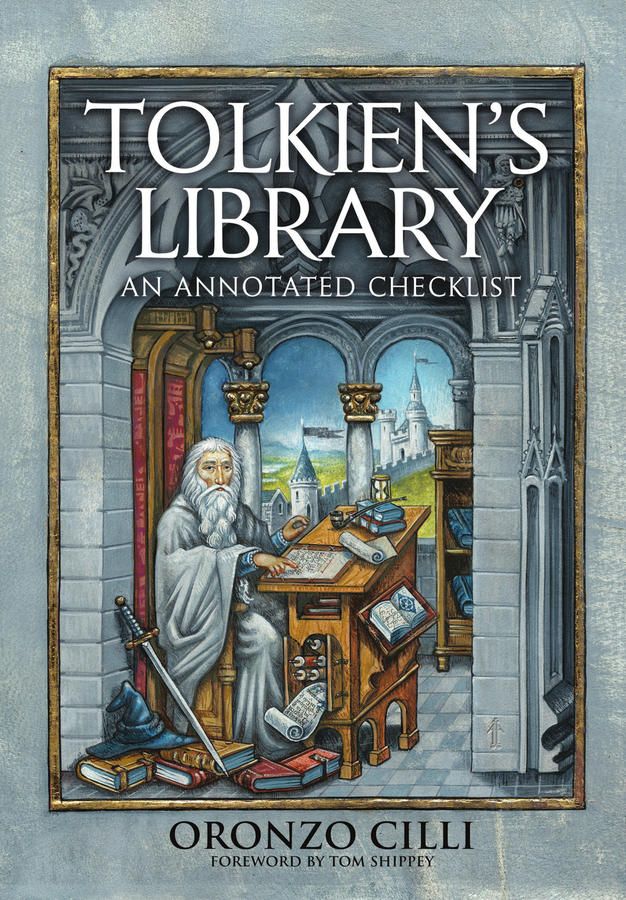

Oronzo Cilli’s wonderfully detailed work, Tolkien’s Library, An Annotated Checklist,

using a variety of sources, from correspondence, to the comments of his friends, to books surviving in university collections, to sale catalogues, to library books recorded to have been checked out by him, supplies us with hundreds of titles owned or consulted by Tolkien.

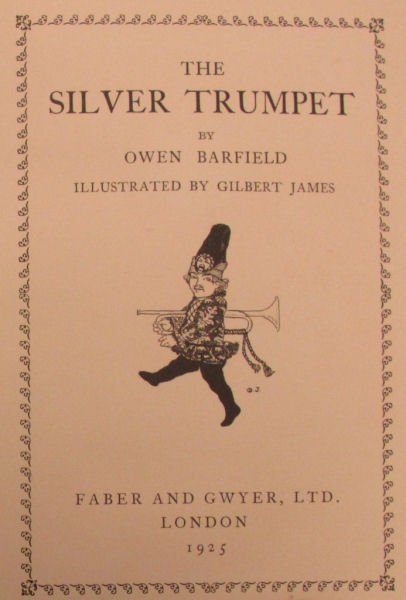

For a person who often wrote that he was overwhelmed with academic work year-round, however, Tolkien appears to have enough leisure to accumulate and read quite a number of non-scholarly works, as well, and leafing through the pages of Cilli’s book, one finds everything from Owen Barfield’s The Silver Trumpet

to James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake

(although Cilli misspells it with an apostrophe, which Joyce intentionally didn’t employ)

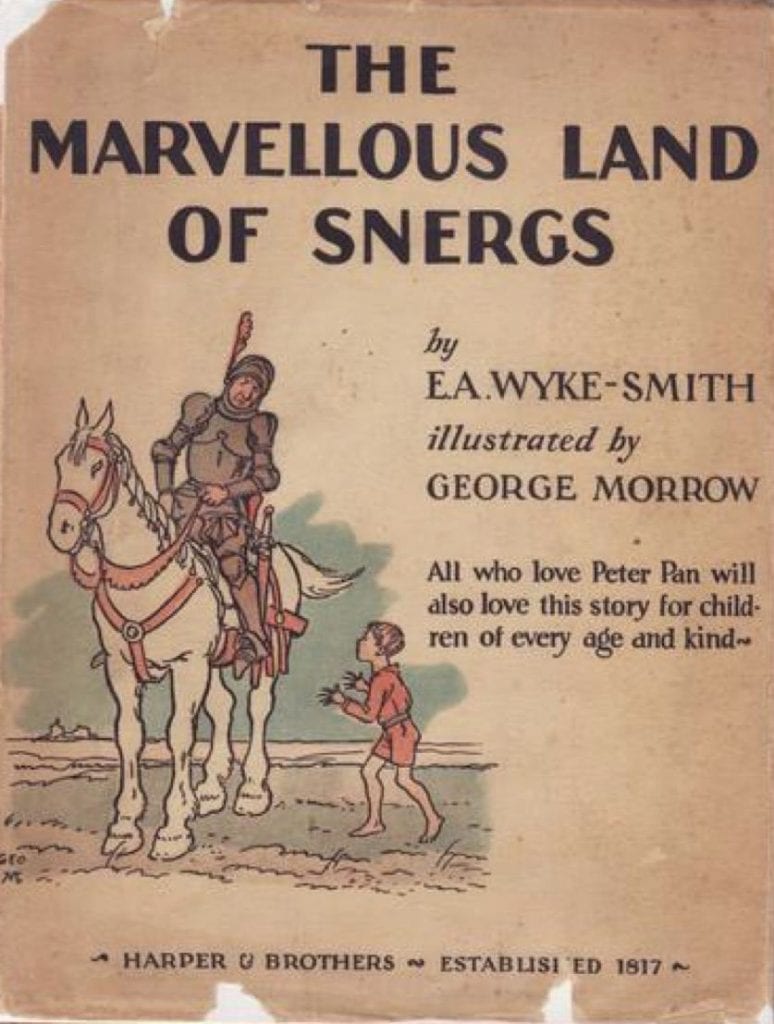

to E.A. Wyke-Smith’s The Marvellous Land of Snergs.

(missing its definite article in Cilli)

Among his listings are these:

Busman’s Honeymoon,

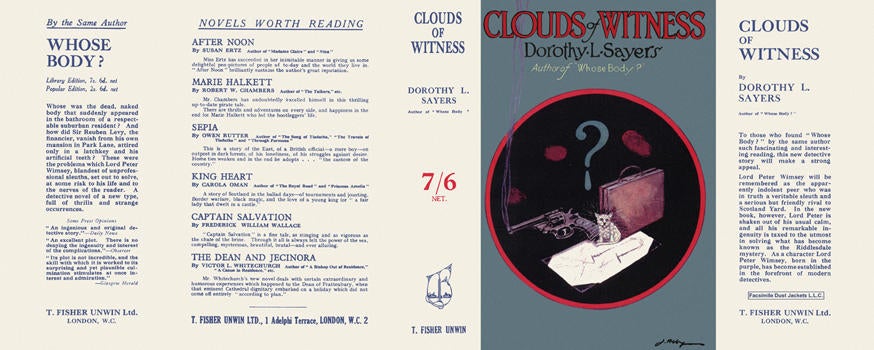

Clouds of Witness,

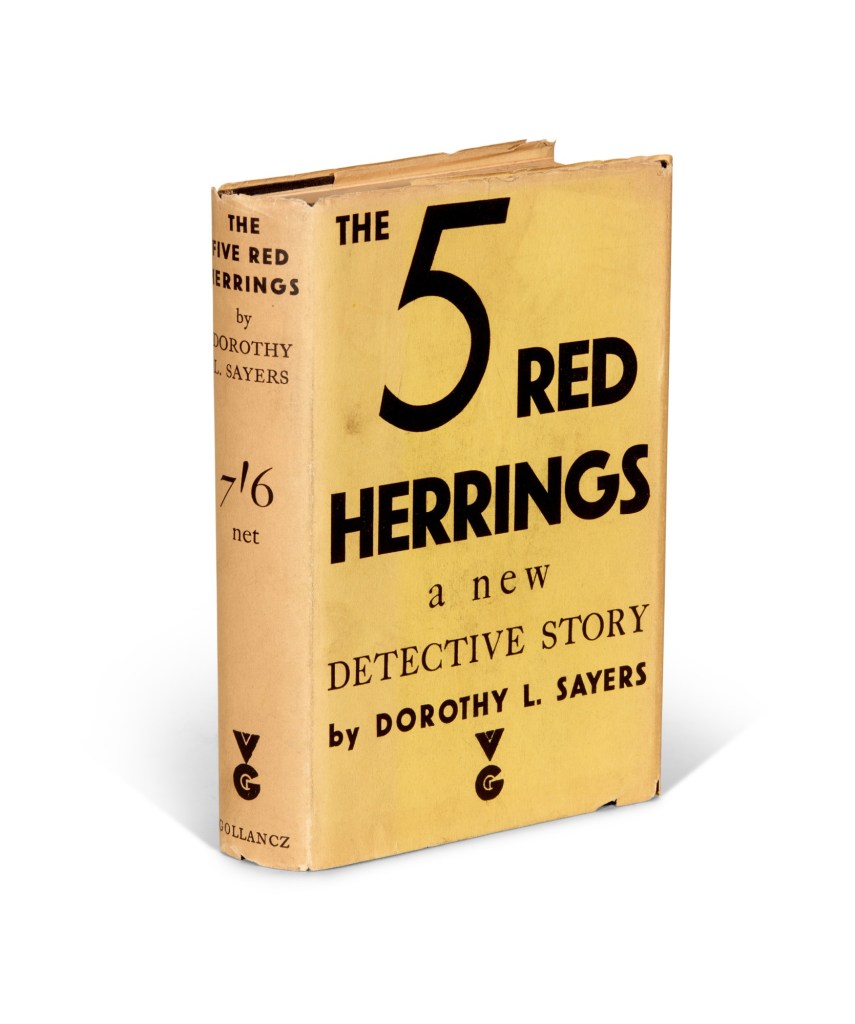

The Five Red Herrings,

(also missing its definite article in Cilli)

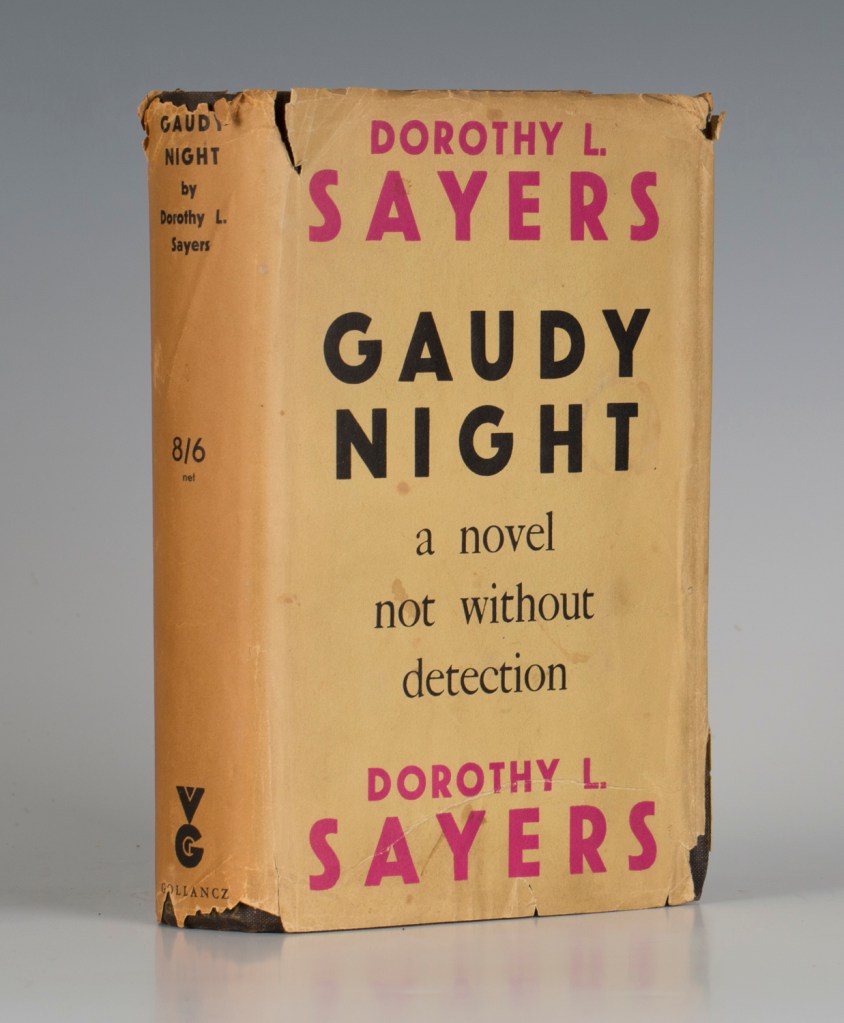

Gaudy Night,

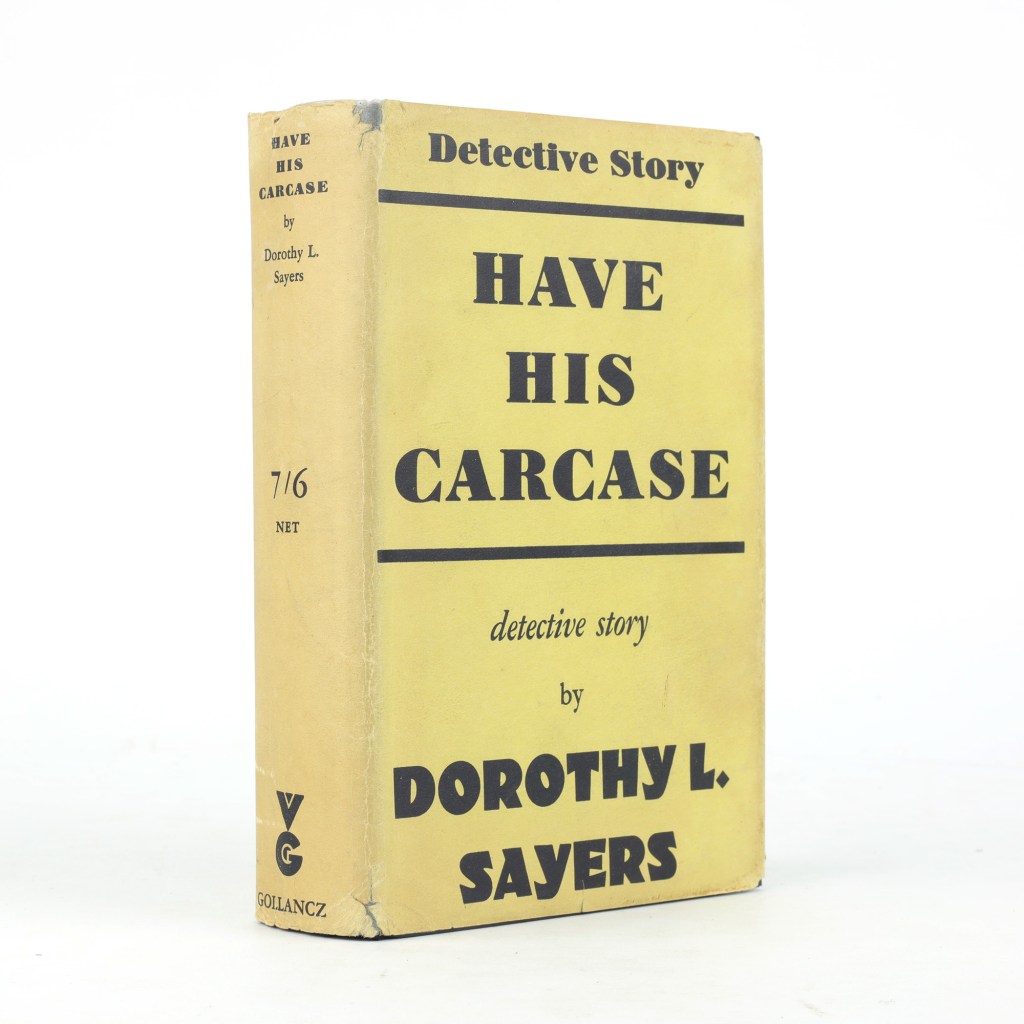

Have His Carcase,

Murder Must Advertise,

Strong Poison,

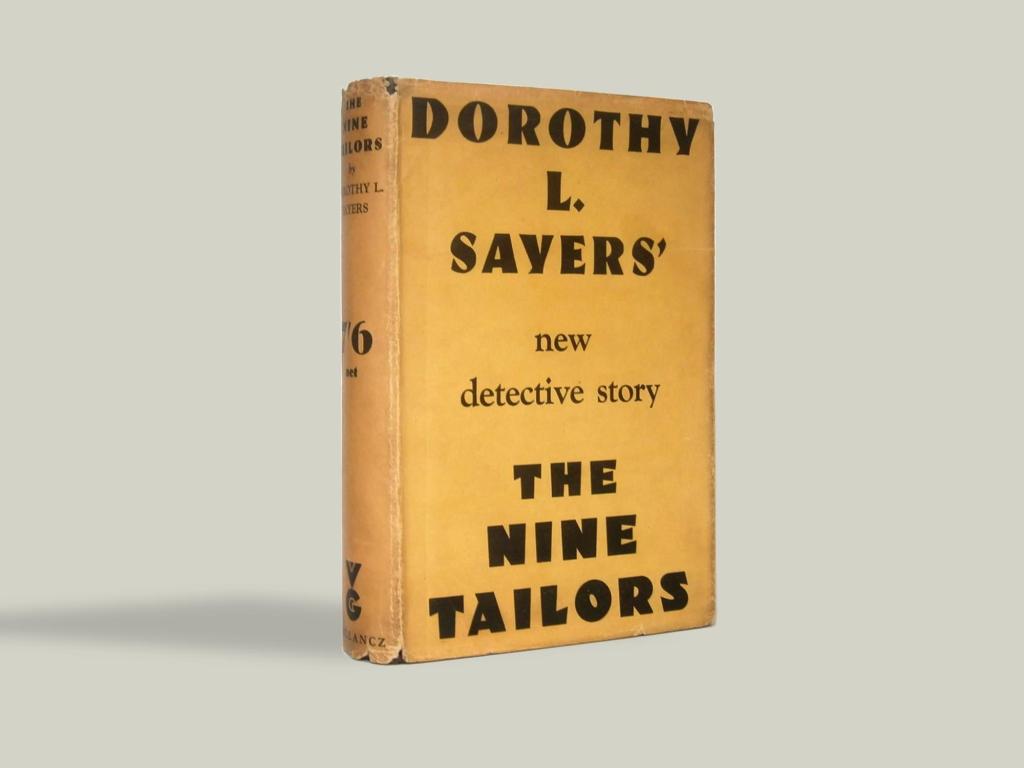

The Nine Tailors,

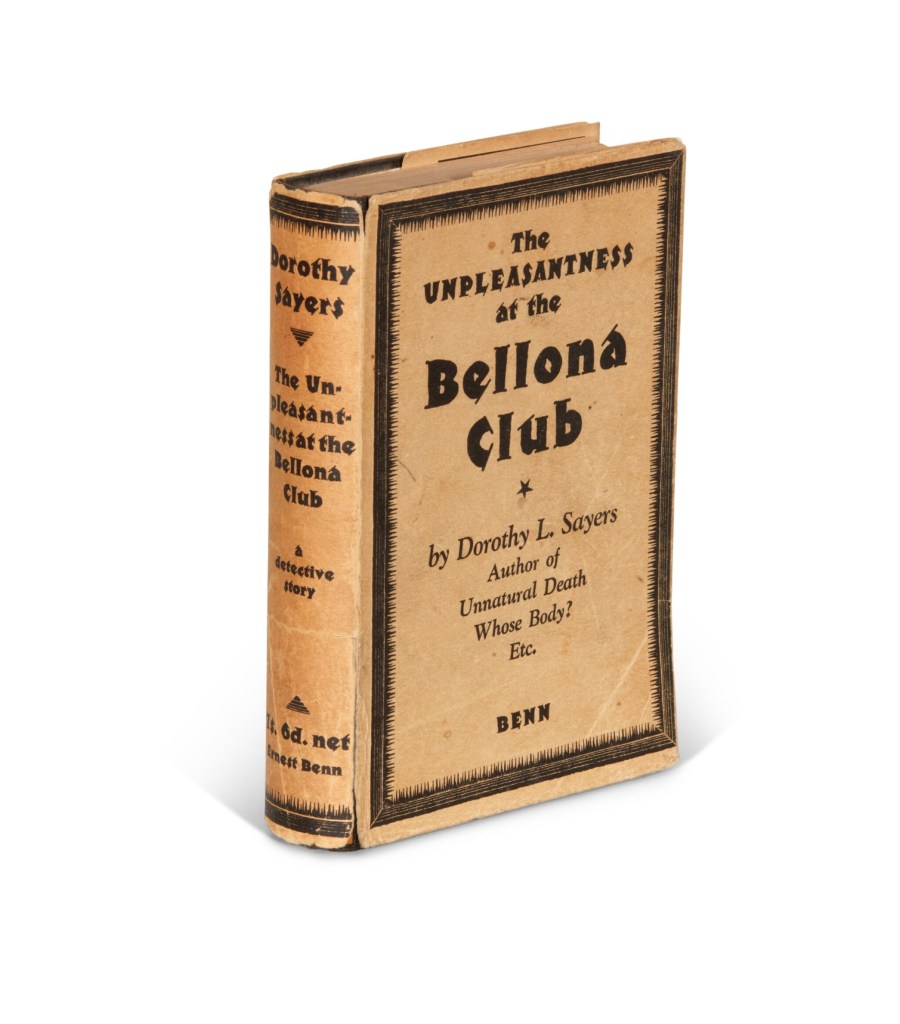

The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club,

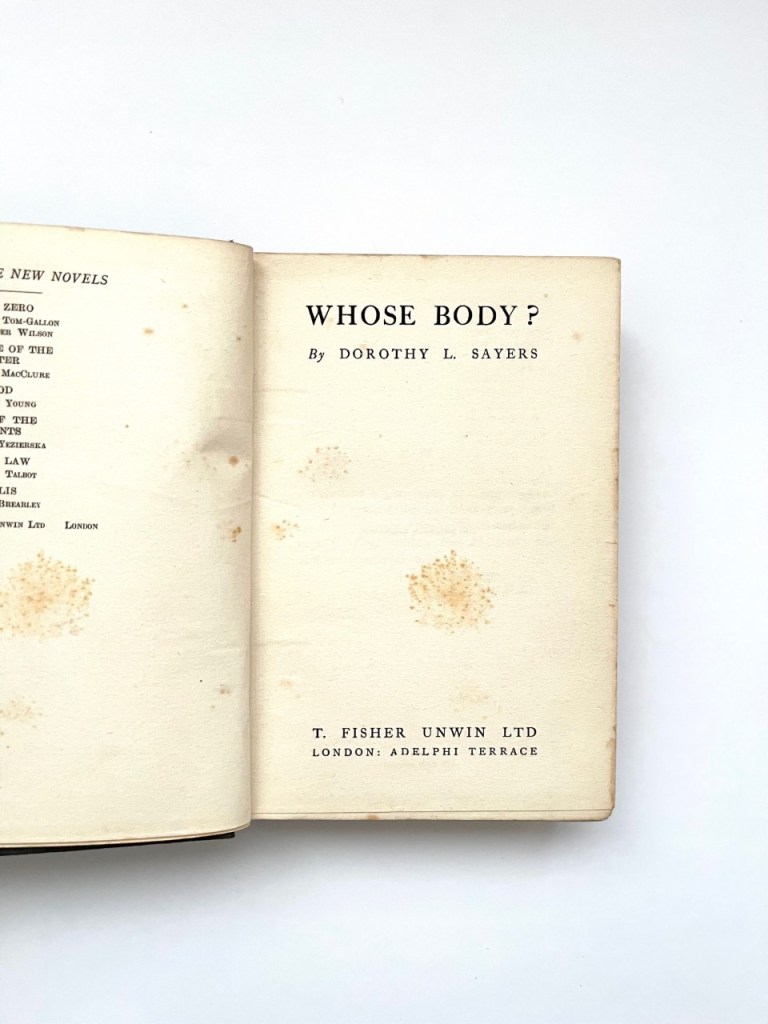

and Whose Body?,

all detective novels by Dorothy L. Sayers (1893-1957).

In these novels, the detective is a wealthy, titled man, Lord Peter Wimsey,

who has a kind of Watson in his personal valet, Bunter (a sergeant in his regiment in the Great War, who rescued him on the battlefield), and who eventually marries—of all people—a young mystery writer, Harriet Vane, after he rescues her from the gallows in Strong Poison (1930)–although not immediately. In a very believable rejection, Harriet refuses him at first because she doesn’t believe that gratitude is enough of a basis for a lasting relationship. It takes two more adventures—Have His Carcase, 1932, and Gaudy Night, 1935, before she finally agrees. And, in Sayers’ last Wimsey novel, Busman’s Honeymoon, 1937, we see them just after their marriage.

Besides being a successful mystery writer, Sayers was also a dramatist, essayist, and translator, her major work being her highly-annotated translation of the first two parts of Dante’s Commedia (the third part, unfinished at her death, was completed by Barbara Reynolds).

Both Tolkien and C.S. Lewis knew and liked her, as Humphrey Carpenter tells us (see The Inklings, 189), and, among her works, her series of Christian radio plays, The Man Born to Be King (1941-42), impressed them, but Lewis tried Gaudy Night and didn’t enjoy it, and Tolkien, who appears to have owned and read almost all of her novels (only missing from the list is Unnatural Death, 1927) ultimately wrote this:

“I could not stand Gaudy Night, I followed P. Wimsey from his attractive beginnings so far, by which time I conceived a loathing for him (and his creatix) not surpassed by any other character in literature known to me, unless by his Harriet. The honeymoon one (Busman’s H.?) was worse. I was sick.” (airgraph to Christopher Tolkien, 25 May 1944, Letters, 82)

What had gone wrong? Gaudy Night (1935) is set at a reunion of Harriet Vane’s imaginary Oxford college, “Shrewsbury College”, based upon Sayers’ actual college, Somerville, and concerns mysterious acts of anti-feminist vandalism which come to border on open violence. The college head invites Harriet, as a former member of the college, to investigate, which she does against rather significant opposition from some of the faculty. The plot also concerns Peter Wimsey, who, although off on a diplomatic mission for the British government at the beginning of the story, returns in time to participate in the detecting of the guilty party and her motive later in the novel. We don’t know why this turned Tolkien off—perhaps Lewis’ reaction? Perhaps the love story and Harriet’s ultimate agreement to marry Peter? (He did say that he’d come to loathe her, but doesn’t mention her appearance in two earlier novels.) And what had happened to his liking for Sayers herself? Such extreme reactions seem as mysterious as Sayers’ novels and perhaps it would take a literary detective of the quality of Peter Wimsey himself to unravel it.

Thanks for reading, as always.

Stay well,

The science of deduction or induction—which does Holmes practice really?

And know that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC,

O

PS

Unlike Tolkien, I’ve always enjoyed Sayers’ novels, Harriet Vane being a particular favorite character—I wish that Sayers had written at least one book in which she solves a mystery on her own—and, if you’d like to know more about her and her work, try: https://www.sayers.org.uk/ If Peter Wimsey interests you, besides the books, there are two very good and very different television series available:

1. Ian Carmichael played the character in a series created in the 1970s

2. Edward Petherbridge was Wimsey in a briefer series in the late 1980s

There are partisans for each. I enjoy both, Carmichael having the kind of bounce and flair with quotation which makes Wimsey appealing, and Petherbridge displays the inherent melancholy which is Wimsey’s other side (he still has nightmares about the Great War).