As ever, dear readers, welcome.

Although Tolkien often protested that The Lord of the Rings was never meant to be allegorical (allegory being something he didn’t care for), yet:

“That there is no allegory does not, of course, say there is no applicability. There always is. And since I have not made the struggle unequivocal…there is I suppose applicability in my story to present times.” (from a letter to Herbert Schiro, 17 November, 1957, Letters, 262)

As a case in point, let me cite for you Lotho Sackville-Baggins.

The title of this posting, although it may appear to be the acronym for some large, anonymous corporation, is actually a piece of shorthand adapted from one of Tolkien’s letters:

“We knew Hitler was a vulgar and ignorant little cad, in addition to any other defects (or the source of them)…” (letter to Christopher Tolkien, 23-25 September, 1944, Letters, 93)

That Tolkien had no love for Hitler, his view of him he makes very clear in an earlier letter written to his second son, Michael:

“Anyway, I have in this War a burning private grudge—which would probably make me a better soldier at 49 than I was at 22: against that ruddy little ignoramus Adolf Hitler…” (letter to Michael Tolkien, 9 June, 1941, Letters, 55)

Tolkien goes on in that later letter, however:

… but there seem to be many v. and i.l. cads who don’t speak German…”

and this leads us in a very interesting direction:

“…and who given the same chance would show most of the other Hitlerian characteristics.”

This, in turn, is what leads me to think immediately of Lotho, the son of Otho and Lobelia Sackville-Baggins, whom we first see in the last chapter of The Hobbit, where, having believed that Bilbo was dead, they seem to have hoped to inherit Bag End, appearing at the auction of its contents and, to Bilbo’s mind, intent upon acquiring more than the real estate:

“Many of his silver spoons mysteriously disappeared and were never accounted for. Personally he suspected the Sackville-Bagginses.”

They were clearly personally affronted that Bilbo survived his adventure:

“On their side they never admitted that the returned Baggins was genuine, and they were not on friendly terms with Bilbo ever after. They really had wanted to live in his nice hobbit-hole so very much.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 19, “The Last Stage”)

Although not on friendly terms, perhaps, they were invited to Bilbo’s birthday party, but they presumed upon this, when Bilbo had disappeared, to confront Frodo:

“The Sackville-Bagginses were rather offensive. They began by offering him bad bargain-bargain prices (as between friends) for various valuable and unlabelled things. When Frodo replied that the only things specially directed by Bilbo were being given away, they said the whole affair was very fishy.

‘Only one thing is clear to me,’ said Otho, ‘and that is that you are doing exceedingly well out of it. I insist on seeing the will.”

And now we see what has been festering since that moment, sixty years before, when Bilbo had reappeared to stop the auction:

“Otho would have been Bilbo’s heir, but for the adoption of Frodo.”

He reads the will, finds it ironclad, and is more than disappointed:

“ ‘Foiled again!’ he said to his wife. ‘And after waiting sixty years. Spoons? Fiddlesticks!’ He snapped his fingers under Frodo’s nose and stumped off. But Lobelia was not so easily got rid of. A little later Frodo came out of the study to see how things were getting on, and found her still about the place, investigating nooks and corners, and tapping the floors. He escorted her firmly off the premises, after he relieved her of several small (but rather valuable) articles that had somehow fallen inside her umbrella.”

(Otho might have been waiting for sixty years to gain Bag End, but Bilbo had not forgotten his suspicion of the Sackville-Bagginses’ earlier behavior, leaving a gift for her:

“For LOBELIA SACKVILLE-BAGGINS, as a PRESENT on a case of silver spoons.” The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 1, “A Long-expected Party”)

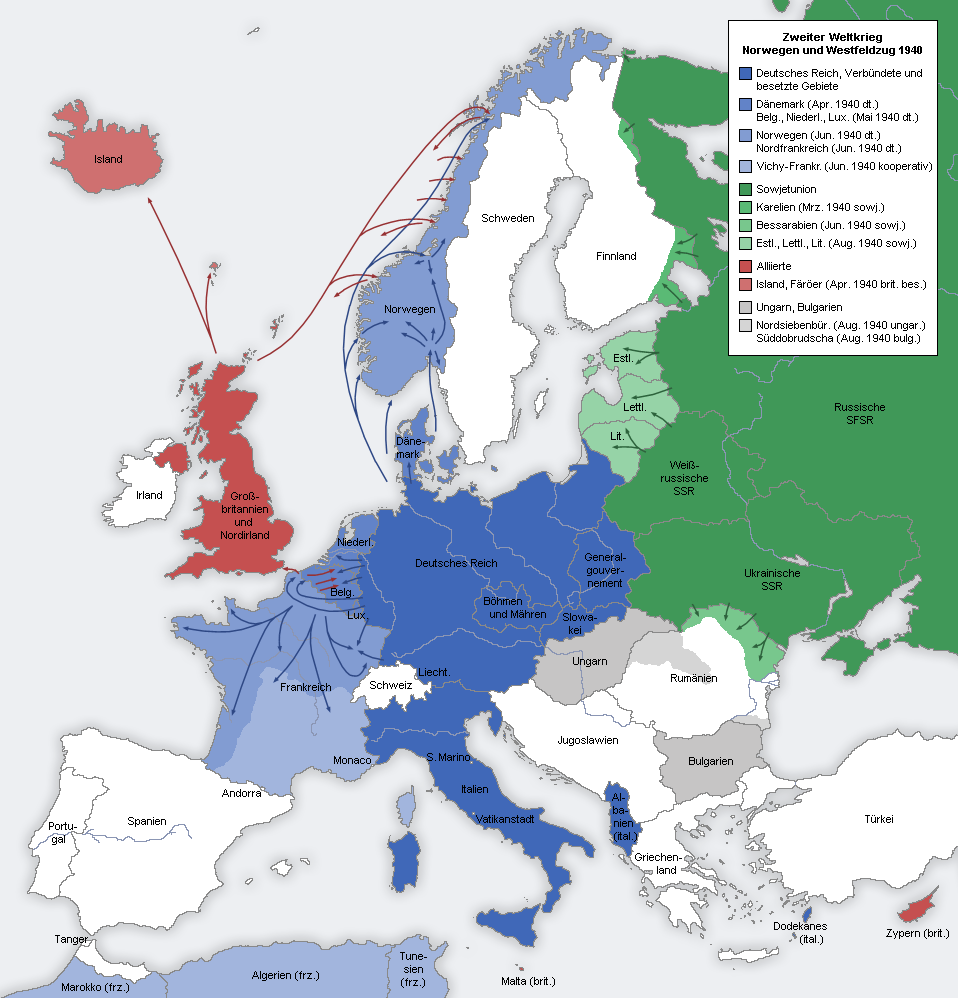

Although Otho had died in the interim, Lobelia survived to buy—not inherit—Bag End, and it was still in her—, or rather, her son, Lotho’s—hands when Saruman, aka “Sharkey”, arrived to continue his plan either to convert the Shire into an early industrial center or to ruin it (Tolkien might have said, “Both”, considering his aversion to what the Industrial Revolution had done to his beloved countryside).

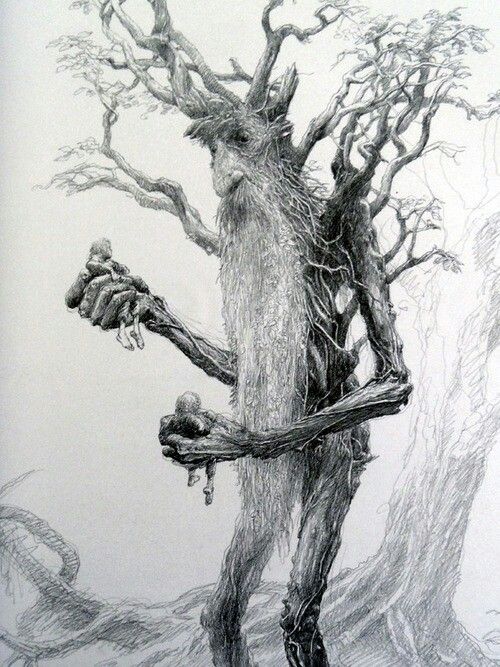

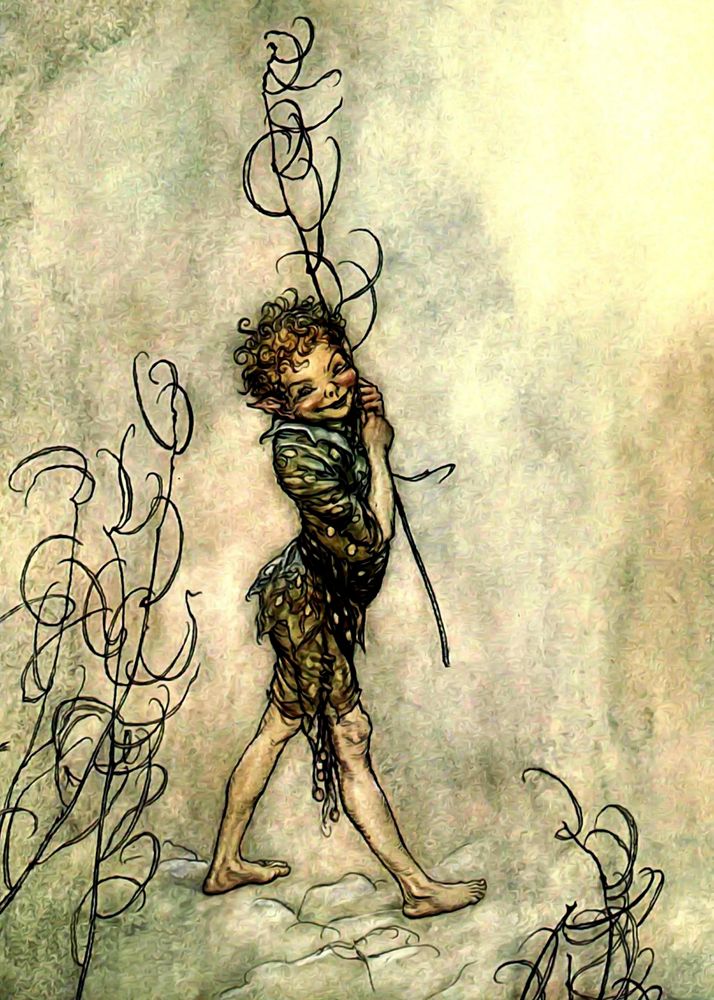

(Denis Gordeev—for an interesting article on Soviet artists’ attempts to bring Tolkien to Russia, see: https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/07/24/soviet-union-tolkien-art-dissidents/ )

In the meantime, Lotho—the son of rather less than decent folk, his own popularity in the Shire gauged by his nickname, “Pimple”—has somehow done very well for himself:

“ ‘It all began with Pimple, as we call him,’ said Farmer Cotton; ‘and it began as soon as you’d gone off, Mr. Frodo. He’d funny ideas, had Pimple. Seems he wanted to own everything himself, and then order other folk about. It soon came out that he already did own a sight more than was good for him; and he was always grabbing more, though where he got the money was a mystery: mills and malt-houses and inns, and farms, and leaf-plantations. He’d already bought Sandyman’s mill before he came to Bag End, seemingly.’ “

Things quickly went from bad to worse, as:

“ ‘A lot of Men, ruffians mostly, came with great wagons, some to carry off the goods south-away, and others to stay. And more came. And before we knew where we were they were planted here and there all over the Shire, and were felling trees and digging and building themselves sheds and houses just as they liked. At first goods and damage was paid for by Pimple; but soon they began lording it around and taking what they wanted.

Then there was a bit of trouble, but not enough. Old Will the Mayor set off for Bag End to protest, but he never got there. Ruffians laid hands on him and took and locked him up in a hole in Michel Delving, and there he is now. And after that, it would be after New Year, there wasn’t no more Mayor, and Pimple called himself Chief Shirriff, or just Chief, and did as he liked…’ “ (The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 8, “The Scouring of the Shire”)

So, from being simply the son of greedy, self-important hobbits, Lotho (and, yes, that has to be a joke on “Loathe-0”) has become, at least until Saruman appears, the dictator of the Shire:

“ ‘…and if anyone got “uppish” as they called it, they followed Will.’ “

Earlier in this same letter to Christopher, Tolkien had written:

“There was a solemn article in the local paper seriously advocating systematic exterminating of the entire German nation as the only proper course after military victory: because, if you please, they are rattlesnakes, and don’t know the difference between good and evil!”

Tolkien, who was a decent and extremely fair-minded man, refuted that, saying:

“The Germans have just as much right to declare the Poles and Jews exterminable vermin, subhuman, as we have to select the Germans: in other words, no right, whatever they have done.”

At the same time, he was well aware that those who may appear ordinary, but who harbor such terrible ideas, may, in time come into positions of control, like Lotho:

“The Vulgar and Ignorant Cad is not yet a boss with power; but he is a very great deal nearer to becoming one in this green and pleasant isle than he was.”

And, if such thinking weren’t wicked enough in itself, there is the added danger:

“You can’t fight the Enemy with his own Ring without turning into an Enemy; but unfortunately Gandalf’s wisdom seems long ago to have passed with him into the True West…”

This seems too much, even for Tolkien, horrified that letters which sound like Nazi propaganda translated into English should appear in the public press and has already written to Christopher that:

“Still you’re not the only one who want to let off steam or bust, sometimes; and I could make steam, if I opened the throttle, compared with which (as the Queen said to Alice) this would be only a scent-spray.”

(a half-quotation from Through the Looking Glass, 1871, where, in Chapter 2, Alice has a conversation with the Red Queen in which the Queen several times uses the expression, “I’ve seen/heard…compared with which…”)

But perhaps there is some consolation in the ultimate fate of Lotho and of his master, Saruman? “Where is that miserable Lotho hiding?” Merry had asked and Saruman later answered:

“ ‘But did I hear someone ask where poor Lotho is hiding? You know, don’t you, Worm? Will you tell them?’

Wormtongue cowered down and whimpered: ‘No, no!’

‘Then I will,’ said Saruman. ‘Worm killed your Chief, poor little fellow, you nice little Boss. Didn’t you, Worm? Stabbed him in his sleep, I believe. Buried him, I hope; though Worm has been very hungry lately…”

This is too much, even for Grima/Wormtongue:

“…suddenly Wormtongue rose up, drawing a hidden knife, and with a snarl like a dog he sprang on Saruman’s back, jerked his head back, cut his throat, and with a yell ran off down the lane.”

In 1944, Tolkien had no idea what would happen to Hitler and his allies by 1945, but one wonders what he might have said about applicability then?

Thanks for reading, as always.

Stay well,

Beware of the self-righteous,

And remember that there’s always

MTCIDC

O