As always, welcome, dear readers.

I wonder if you, like me, have seen something like this on a bumper in a parking lot?

Or possibly stuck on the inside of a car’s back window?

If so, and you are a Tolkien reader, you know right away that it’s one line from a poem by Bilbo, first read in a letter Gandalf has left at The Prancing Pony (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 10, “Strider”) and repeated by Bilbo himself who, at the council of Elrond, “Standing up suddenly…burst[s] out”:

All that is gold does not glitter,

Not all those who wander are lost;

The old that is strong does not wither,

Deep roots are not reached by the frost.

From the ashes a fire shall be woken,

A light from the shadows shall spring;

Renewed shall be blade that was broken:

The crownless again shall be king.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 2, “The Council of Elrond”)

He’s referring to Aragorn, of course, responding both to a dream Boromir has just repeated, as well as to what seems like the beginning of a tussle between Boromir and Aragorn. In his dream, Boromir “heard a voice, remote but clear, crying:

Seek for the Sword that was broken:

In Imladris it dwells;

There shall be counsels taken

Stronger than Morgul-spells.

There shall be shown a token

That Doom is near at hand,

For Isildur’s Bane shall waken,

And the Halfling forth shall stand.”

The broken blade is Narsil, Elendil’s sword, which broke when, killed by Sauron, he fell on it. Isildur then used the shard to cut the Ring (which became “Isildur’s Bane”, or curse) from Sauron’s hand and so the Ring and the shattered sword are forever linked.

Bilbo’s poem then acts as a kind of second stanza to Boromir’s dream verses, suggesting that the shattering of the sword is not the end of the story and that its remaking will be involved in the Doom of Boromir’s poem.

For all the weight in these words, the line which caught my attention this time was: “All that is gold does not glitter”.

This is, of course, based upon “all that glitters isn’t gold”, from the proverbial expression, believed to originate in the Parabolae, “Proverbs”, of the 12th century French cleric Alain de Lille, who wrote:

Non teneas aurum totum quod splendet ut aurum

nec pulchrum pomum quodlibet esse bonum;

“Do not take for gold all which shines like gold

Nor a good-looking apple, if you will, to be a good one.” (Liber Parabolarum, 3.1, my translation)

And yet there is something odd here—instead of saying what the proverb warns: “don’t trust surfaces”, Bilbo is suggesting that “Some things which don’t glitter are gold”, implying that an unlikely surface may hide something worthy and there is more to the rough-looking Aragorn than Boromir—or anyone else in the room who doesn’t know his history—may understand.

It might be thought that Tolkien didn’t like Shakespeare, and this idea comes, I would guess, from this quotation in particular:

“I went to King Edward’s School and spent most of my time learning Latin and Greek; but I also learned English. Not English Literature! Except Shakespeare (which I disliked cordially)…” (letter to W.H. Auden, 7 June, 1955, Letters, 213)

And yet he later records enjoying a performance of Hamlet—and here, I think, we can see that what he might dislike isn’t Shakespeare per se, but reading him as one might read a novel:

“…but the only event worth of talk was the performance of Hamlet which I had been to just before I wrote last. I was full of it at the time…But it emphasized more strongly than anything I have ever seen the folly of reading Shakespeare (and annotating him in the study), except as a concomitant of seeing his plays acted.” (letter to Christopher Tolkien, 28 July, 1944, Letters, 88)

And I wonder, then, if Bilbo’s line, and his point, weren’t, in fact, influenced by another Shakespeare play.

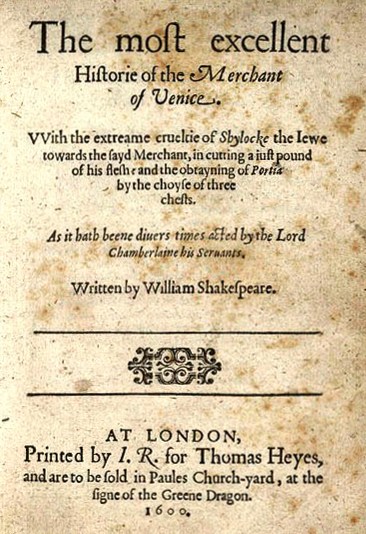

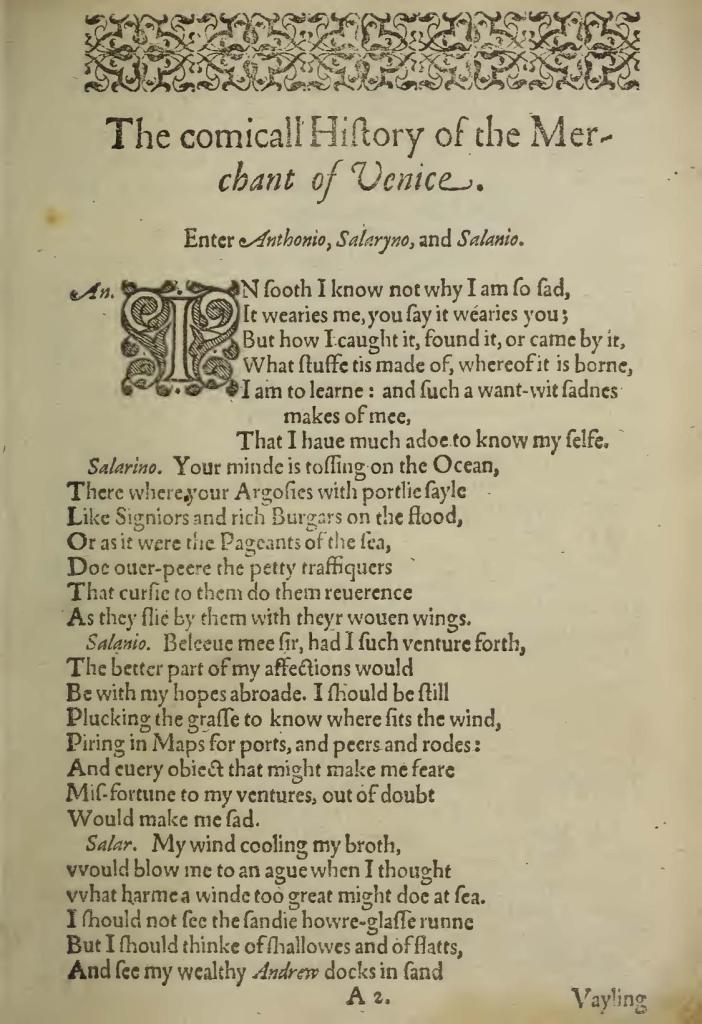

(The First Quarto, 1600—and here it is for you: https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/MV_Q1/complete/index.html )

As with all of Shakespeare’s plays, there is a complicated plot, but there is one element, as old as the 13th century Gesta Romanorum, “The Deeds of the Romans” (which Shakespeare probably read in the 1577 Certain Selected Histories for Christian Recreations. You can read the story, Number XLVIII, here: https://ia600902.us.archive.org/15/items/gestaromanorum02hoopgoog/gestaromanorum02hoopgoog.pdf pages XLIV-XLVII ) which involves a kind of contest for the daughter/heiress of a wealthy man. Her father has arranged three caskets, one of gold, one of silver, and one of lead, with a riddling, ironic label on each and the suitor who picks the correct one (which has the daughter, Portia’s, portrait inside) gains her hand. We in the present cynical world would roll our eyes and say, “It’s the lead one, of course!” but Shakespeare’s audience would be as well aware of this as we are. The point is really about the revelation of character, the choice each of the suitors makes reveals his quality as we overhear each talking to himself before making his decision (and this is one reason why this play was called “The comical Historie of the Merchant of Venice” on the first page of the text, for all that it has its moments of passion and even danger).

The first, Morochus (as he’s called in the First Quarto), chooses the casket of gold because:

“One of these three containes her heauenly picture.

Ist like that leade containes her, twere damnation

to thinke so base a thought, it were too grosse

to ribb her serecloth in the obscure graue,

Or shall I thinke in siluer shees immurd

beeing tenne times vndervalewed to tride gold,

O sinful thought, neuer so rich a Iem

was set in worse then gold.” (Act II, Scene 7—this is a later division of the text, the First Quarto runs straight through)

He’s wrong, of course, but what’s telling is that he can only see the outside of the casket, as he really only sees—and values– the outside of Portia, thus revealing his shallowness. He opens the casket and finds only this mocking message:

“All that glisters is not gold,

Often haue you heard that told,

Many a man his life hath sold

But my outside to behold,

Guilded timber doe wormes infold:

Had you beene as wise as bold,

Young in limbs, in iudgement old,

Your aunswere had not beene inscrold,

Fareyouwell, your sute is cold.”

The second suitor, the Prince of Arragon, chooses the silver casket, and he, too, fails. It’s only the third, Bassanio, whom Portia really likes, who makes the correct choice, finding her portrait in the casket of lead and, in his reasoning and choice, we see that he is a far different character from the two previous suitors, as his enclosed poem says:

“You that choose not by the view

Chaunce as faire, and choose as true:

Since this fortune falls to you,

Be content, and seeke no new.

If you be well pleasd with this,

and hold your fortune for your blisse,

Turne you where your Lady is,

And claime her with a louing kis.”

The key here is that first line: “You that choose not by the view”—and this brings us back to something which Frodo had said of Strider/Aragorn long before:

“ ‘You have frightened me several times tonight, but never in the way that servants of the Enemy would, or so I imagine. I think one of his spies would—well, seem fairer and feel fouler, if you understand.’

‘I see,’ laughed Strider. ‘I look foul and feel fair. Is that it? All that is gold does not glitter, not all those who wander are lost.’” (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book One, Chapter 10, “Strider”)

For all that JRRT might write, “a murrain on Will Shakespeare and his damned cobwebs”, perhaps, somewhere in those cobwebs, was caught a moment of inspiration?

As ever, thanks for reading,

Stay well,

Choose wisely,

And remember that there’s always

MTCIDC

O

PS

Here’s another bumper sticker which I sometimes feel is true for me—and perhaps for you, as well?