As ever, dear readers, welcome.

In my last, I began a brief series based upon my second thoughts (the first appeared as “Knowledge, Rule, Order”, 6 January, 2016 at Doubtfulsea.com) about the words in the title.

The original speaker was Saruman, who uses those three words in his proposal of alliance with Gandalf.

“A new Power is rising…We may join with that Power. It would be wise, Gandalf. There is hope that way…As the Power grows, its proved friends will also grow; and the Wise, such as you and I, may with patience come at last to direct its courses, to control it. We can bide our time…deploring maybe evils done by the way, but approving the high and ultimate purpose: Knowledge, Rule, Order. All the things that we have so far striven in vain to accomplish…There need not be, there would not be, any real change in our designs, only in our means.” (The Fellowship of the Rings, Book Two, Chapter 2, “The Council of Elrond”)

Gandalf immediately dismisses Saruman’s attempt, saying “I have heard speeches of this kind before, but only in the mouths of emissaries sent from Mordor to deceive the ignorant…” but, in the first of this little series, I spent some time considering the first of his three words, “Knowledge”, which Saruman has claimed as one of “the things we have so far striven in vain to accomplish”.

We know that the five Istari, the five “wizards”, were originally sent to Middle-earth by the Valar as a kind of counterbalance to Sauron. As far as I understand their mission, that was their goal, with no mention of “the high and ultimate purpose: Knowledge, Rule, Order”. In last week’s posting, I suggested that what Saruman believed was that that abstract “Knowledge” had actually become Saruman’s knowledge—a knowledge he meant to employ not just to counter Sauron, but to become Sauron, wielding the rediscovered Ring as the new master of Middle-earth. Ironically, however, through a combination of his own growing arrogance and by Sauron’s clever manipulation of it, by means of the palantir which had come into Saruman’s possession,

Saruman’s knowledge had become Sauron’s knowledge and Saruman only a deluded henchman of the creature he had been sent to oppose.

But what about “Rule”?

It’s important to remember that Tolkien was born into a world where almost all of the major—and most of the minor—European powers were controlled by monarchies. In 1914, just before war broke out, not only was the British Empire in the hands of George V,

but his cousin, Wilhelm, ruled the German Empire,

and another cousin, Nicholas, ruled the Russian Empire.

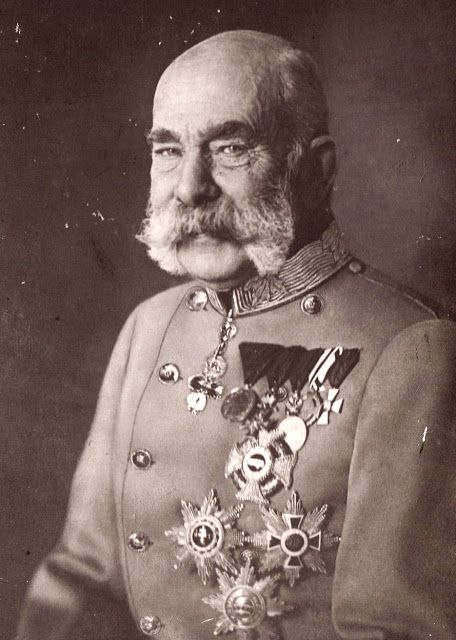

And this is to name only what we might call “the big three”—to which we should add the Emperor of Austria-Hungary, Franz Josef.

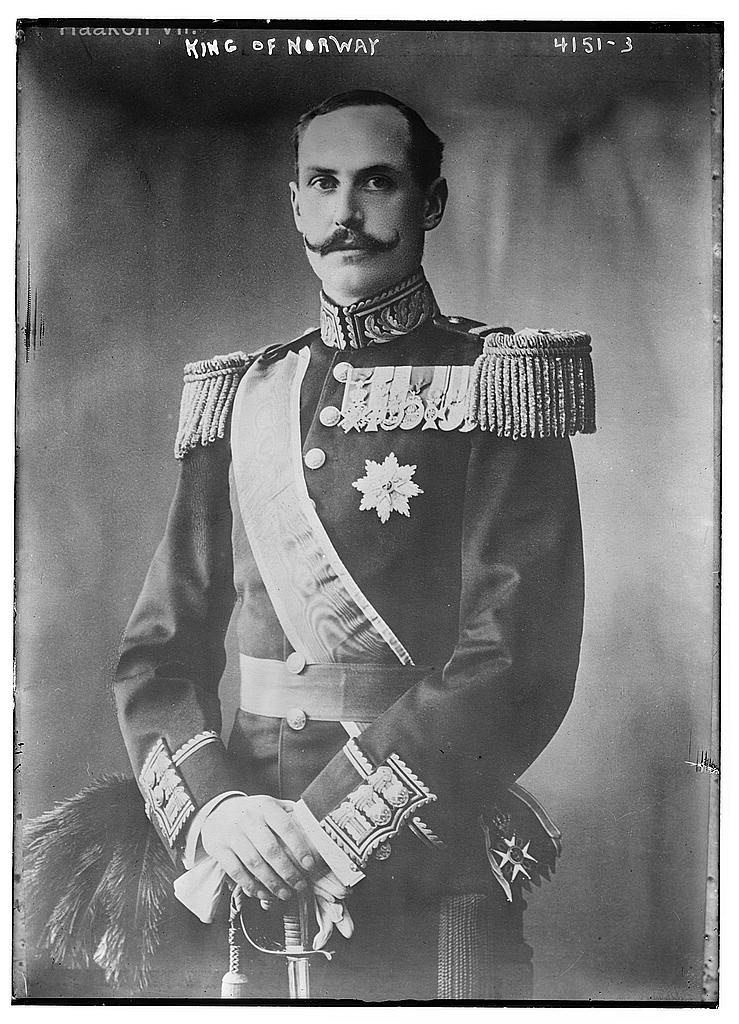

There were also monarchs from Norway

to Belgium

to Italy

to Spain,

with rulers in Greece

and many other smaller countries, like Serbia

and Bulgaria.

This is not all of such folk (the Netherlands had a queen, for example), but we might also include the Turkish sultan, Mehmed V.

Of all the European countries, only Switzerland and France were democracies, in fact. That being the case, when JRRT used the word “Rule”, we can easily imagine what must have come to mind. (And yet we should also keep in mind what he once wrote to his son, Christopher: “My political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy”—although he goes on to add “or to ‘unconstitutional Monarchy…Give me a king whose chief interest in life is stamps, railways, or race-horses…”, all of which suggests that he had come, at least by the 1940s, to have serious doubts about royal rule. See letter to Christopher Tolkien, 29 November, 1943, Letters, 63-64)

For Saruman, there were three models readily to hand: Rohan, Gondor, and Mordor. As for Rohan, he doesn’t appear to have much respect, saying,

“What is the house of Eorl but a thatched barn where brigands drink in the reek, and their brats roll on the floor among the dogs?” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 10, “The Voice of Saruman”)

It would appear that he has no more respect for Gondor, as he refers to it, in his attempt to enlist Gandalf, as “dying Numenor”.

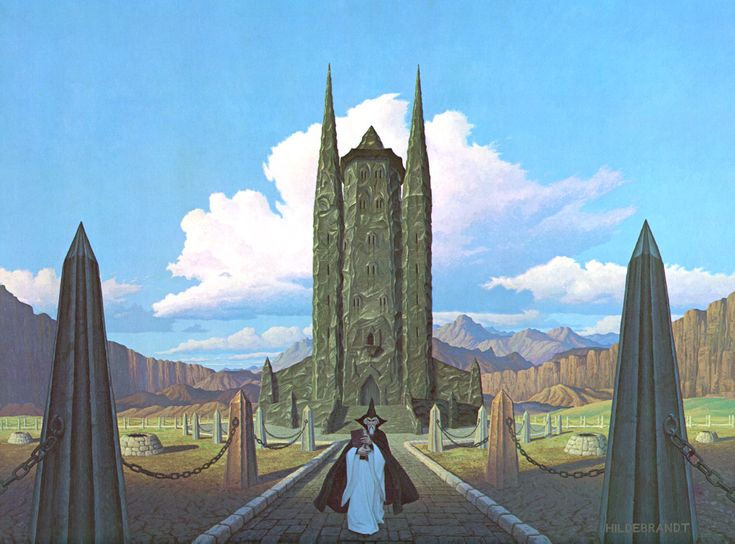

And this leaves us with Mordor and it’s clear that this has become Saruman’s model, albeit not quite the impressive alternate version he believes it to be. As the narrator says of Isengard:

“A strong place and wonderful was Isengard…But Saruman had slowly shaped it to his shifting purposes, and made it better, as he thought, being deceived—for all those arts and subtle devices, for which he forsook his former wisdom, and which he fondly imagined were his own, came but from Mordor; so that what he made was naught, only a little copy, a child’s model or a slave’s flattery, of that vast fortress, armoury, prison, furnace of great power, Barad-dur, the Dark Tower…” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 8, “The Road to Isengard”)

As well, Saruman imitates Mordor’s economy, which is slave-based, as the narrator tells us of Sam and his master:

“Neither he nor Frodo knew anything of the great slave-worked fields away south in this wide realm, beynd the fumes of the Mountain by the dark sad waters of Lake Nurnen; nor of the great roads that ran away east and south to tributary lands, from the which the soldiers of the Tower brought long wagon-trains of goods and booty and fresh slaves.” (The Return of the King, Book Six, Chapter 2, “The Land of Shadow”)

And the narrator says of Isengard:

“That was a sheltered valley, open only to the South. Once it had been fair and green…It was not so now. Beneath the walls of Isengard there still were acres tilled by the slaves of Saruman…” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 8, “The Road to Isengard”)

Kings in fairy tales sometimes have chancellors or viziers and perhaps faceless servants to fetch and carry, but real medieval kings could have full bureaucracies, with officials of all sorts and clerks and messengers to keep records and maintain contact with royal officials working away from the palace.

Unfortunately, we seem to lack much information about the court structure of Mordor. At its center is Sauron, directing things from the Barad-dur, which he doesn’t appear to leave, employing the Nazgul as senior officers (who, after all, themselves had once been kings),

(Artist?)

as well as a Lieutenant of the Tower, who also acts as a kind of public interpreter or chancellor of some sort, “the Mouth of Sauron”,

(Douglas Beekman)

but, as for more structure, this looks like an interesting subject for further research and a future posting—or perhaps two.

Although Saruman has spies (Grima immediately springs to mind, although he has others),

(Alan Lee)

and a good-sized army of orcs and men (Merry thinks that “there must have been ten thousand at the very least”—The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 9, “Flotsam and Jetsam”), he doesn’t appear to have the equivalent of the Nazgul or the Mouth, directing everything himself (which, considering his arrogance, shouldn’t surprise us), being more like a fairy tale king than the head of 10,000 soldiers and what might be a fairly advanced technological infrastructure below the ground in Isengard (ten thousand soldiers need arms and armor, as well as durable rations, after all)—and all a pale copy of Sauron.

(the Hildebrandts)

So now we see just how unreal Saruman’s expectations have become: his “Knowledge” is at the disposal of a being Saruman isn’t aware controls him, and his “Rule” is nothing more than a petty version of the world of that controller. What will his “Order” be?

As ever, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

Practice aggressive self-awareness (or don’t get involved with devious Maiar),

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O