“An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless…”

(W.B. Yeats, “Sailing to Byzantium”)

As ever, welcome, dear readers.

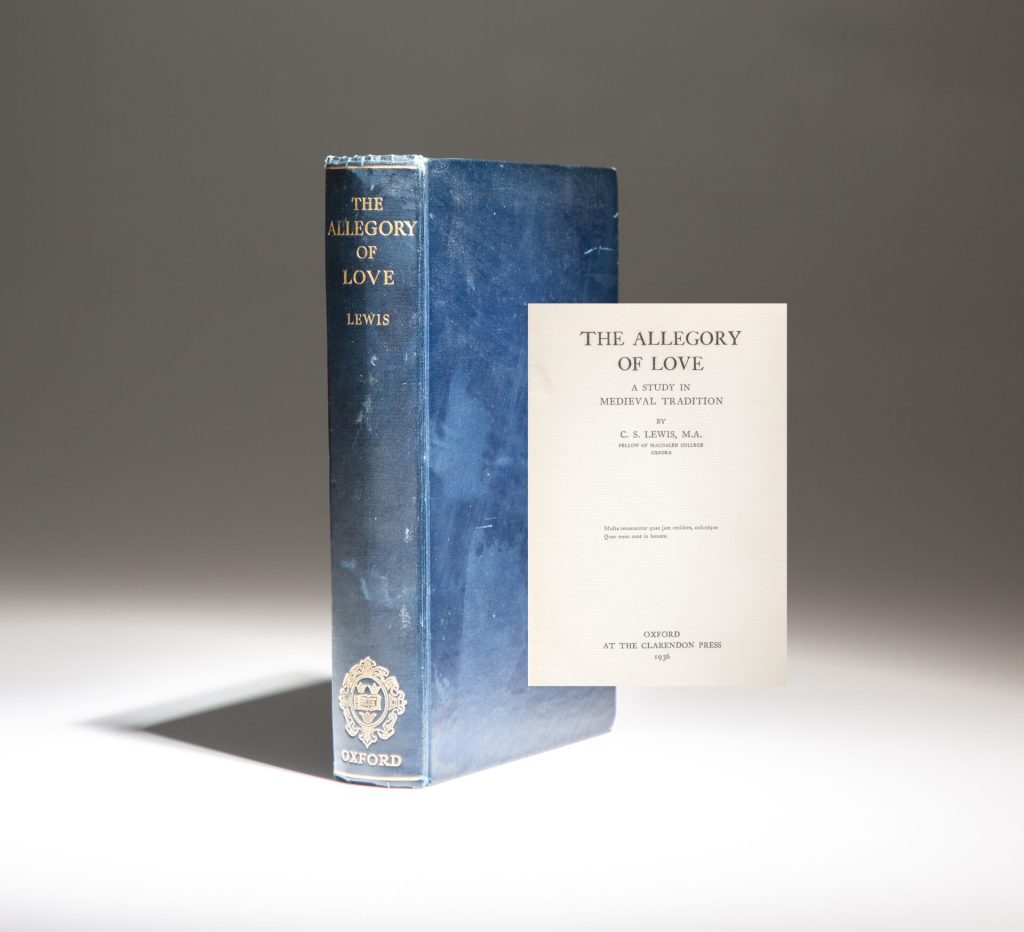

“I dislike Allegory—the conscious and intentional allegory…” Tolkien once wrote in a letter to Milton Waldman of the publisher Collins (see letter to Milton Waldman, “late in 1951” in Letters, 145) so, although he was flattered by being included in the company of Spenser (see letter to Rayner Unwin, 13 May, 1954, Letters, 181), I wonder what he might have said about how this posting originated. (I also wonder how he felt about his friend, C.S. Lewis’

1936 volume, The Allegory of Love.)

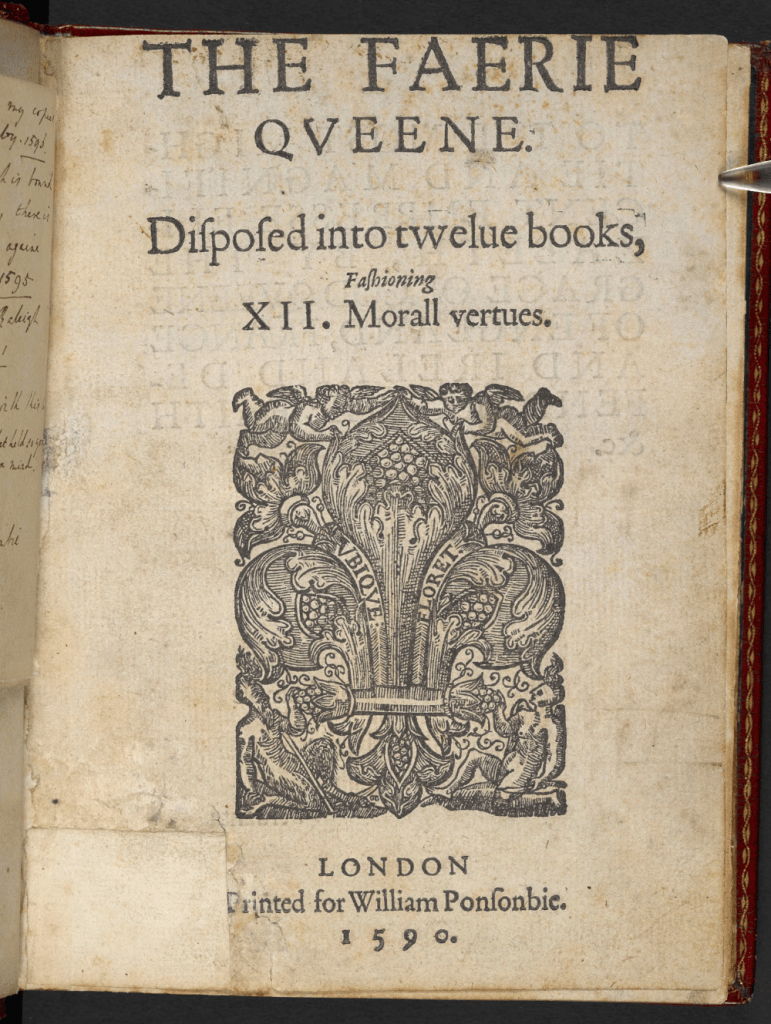

I have been slowly making my way through Edmund Spenser’s (1552-1599)

The Faerie Queene.

(This is the original 3-book publication of 1590—he then published a second 6-book edition in 1596, but never succeeded in completing his original 12-book plan.)

To say that it’s allegorical is about as understated as saying that Hamlet is about indecision or that Macbeth is about ambition gone wrong. Spenser himself cheerfully described his work as “cloudily enwrapped in Allegoricall devises”, the whole purpose being “to fashion a gentleman or noble person in vertuous and gentle discipline” by embodying “the image of a brave knight, perfected in the twelve private morall vertues, as Aristotle hath devised…” (This is all extracted from his dedicatory letter to Sir Walter Raleigh). His heroes are faced by figures with names like “Disdayne”, in books with subtitles like “The Legend of Sir Guyon. Or Of Temperance”, suggesting that, whereas the volume as a whole is “cloudily enwrapped”, the episodes themselves are clearly all about testing various virtues.

I’ve just finished Book Two (that’s about 340 pages in—this is not a short work, even if only half-finished) and have followed the adventures of Sir Guyon and his adviser, called “the Palmer”

—that is, the pilgrim, as medieval pilgrims sometimes brought back souvenir palms from their arduous trip to the Holy Land.

Pilgrims could pick up other such souvenirs at various shrines, such as this badge, depicting the shrine of St Thomas a Becket, from Canterbury.

Also characteristic of palmers/pilgrims was the staff, which could be used for everything from aiding in long hikes to chasing off potential robbers,

and it was this object which caught my attention. At the end of Book Two, Sir Guyon finally defeats Acrasia (something like “Moralweakness”), an enchantress who embodies seduction and sensual pleasure and whose power turns men into beasts. When Guyon destroys her bower, the Palmer uses his staff to turn such men back into themselves:

“Streight way he with his vertuous staffe them stroke,

And straight of beasts they comely men became…”

(The Faerie Queene, Book Two, Canto XII, Stanza 86—earlier in the Canto, the Palmer calmed the sea and its monsters with his staff)

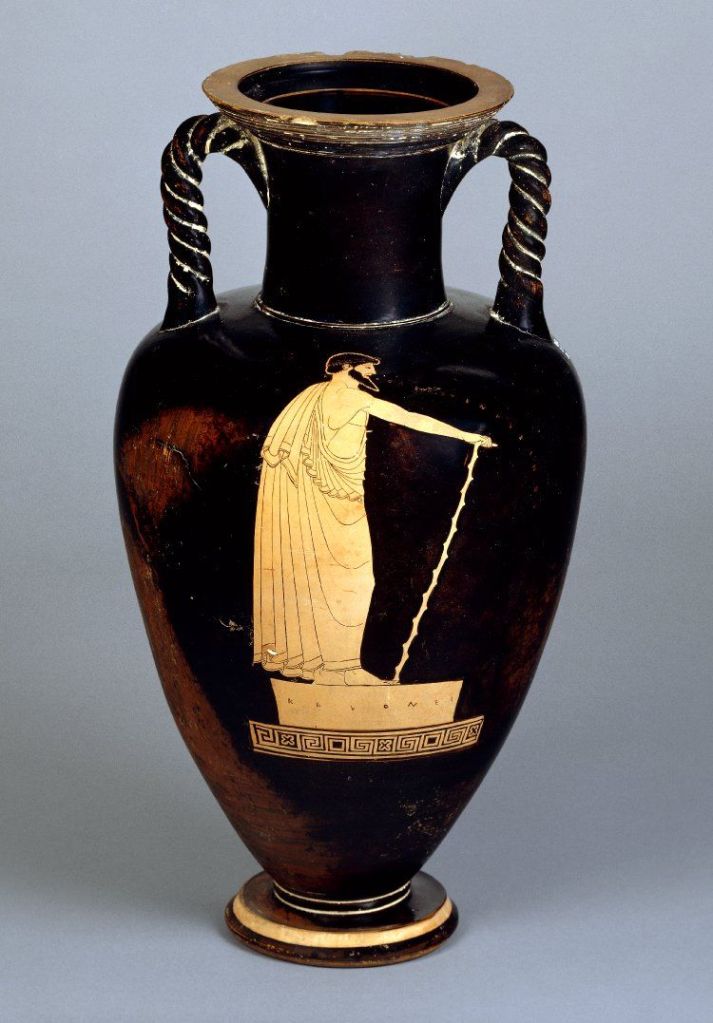

This immediately reminded me, as I’m sure Spenser wanted me to be, of Odyssey, Book 10, where Circe had used a magical potion and her rhabdos, which commonly means a staff in Greek, like the staff which rhapsodes used to beat time when they recited epic, like the Odyssey,

to enchant Odysseus’ men.

(This appears to be an illustration from a late-Renaissance French illustration of the Odyssey and I love the caption: “Companions of Ulysses in Piggly Form”.)

Odysseus himself was saved from this enchantment in part by the counsel of Hermes (his Roman name Mercury),

who carries his own staff, the kerykion (called by the Romans caduceus), and it’s surely no coincidence that Spenser tells us:

“Of that same wood it fram’d was cunningly,

Of which Caduceus whilome was made,

Caduceus the rod of Mercury,

With which he wonts the Stygian realms inuade,

Through ghastly horrour, and eternall shade;

Th’infernall feends with it he can asswage,

And Orcus tame, whom nothing can perswade,

And rule the Furyes, when they most do rage:

Such virtue in his staffe had eke this Palmer sage.”

(The Faerie Queene, Book Two, Canto XII, Stanza 41)

And these staves (the plural of staff) of power reminded me of another staff, of which its owner once said:

“I am old. If I may not lean on my stick as I go, then I will sit out here, until it pleases Theoden to hobble out himself to speak with me.”

(The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 6, “The King of the Golden Hall”)

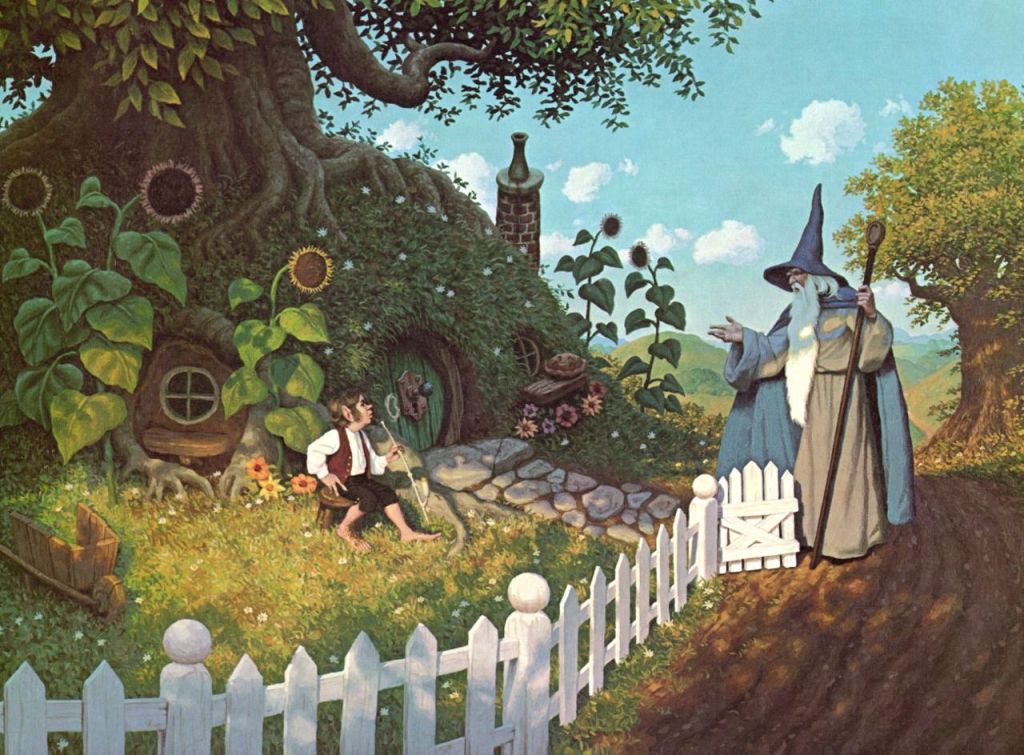

This is Gandalf, of course, who has been associated with that “stick” since we first saw him in Chapter One of The Hobbit.

(the Hildebrandts)

Hama, the doorwarden, was, of course, correct in saying, “The staff in the hand of a wizard may be more than a prop for age…” as Gandalf has previously broken the bridge of Khazan-dum in Moria with that very staff,

(the Hildebrandts)

and will knock Grima, Theoden’s treacherous counselor, flat with it.

(Alan Lee)

And, as Gandalf is aware of what lies in his staff, he knows the power and authority in Saruman’s staff, and so Gandalf will snap it, ruining Saruman’s ability to continue to work the evil he has planned.

(? I don’t know the artist for this, alas!)

Seeing all of these staves, which are more than they appear at first, we might then complete Yeats’ lines like this:

“An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A ragged coat upon a stick, unless

That stick has something of a magic sting

Which only palmers—wizards, too—possess.”

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

If a palmer offers to guide you, stick with him,

And know that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O