As always, dear readers, welcome.

We know that Tolkien had an interest in dragons from an early age. In a letter to W.H. Auden of 7 June, 1955, he explains:

“I first tried to write a story when I was about seven. It was about a dragon. I remember nothing about it except a philological fact. My mother said nothing about the dragon, but pointed out that one could not say ‘a green great dragon’, but had to say ‘a great green dragon’. I wondered why, and still do.” (letter to W.H. Auden, 7 June, 1955, Letters, 214).

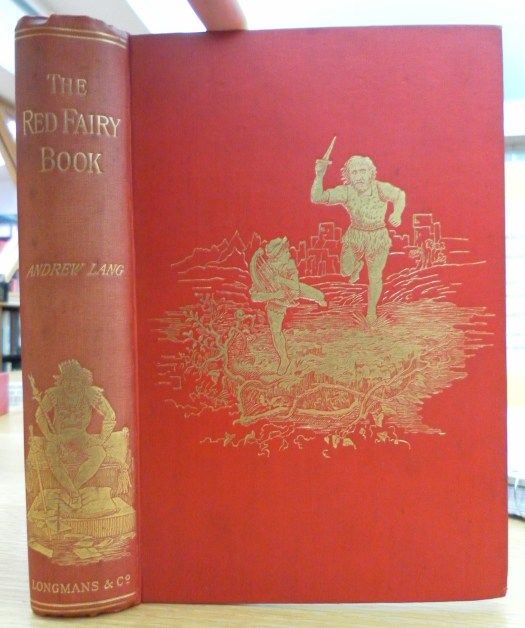

I suspect that this interest had been sparked by a book which we know was available to him in childhood: Andrew Lang’s (1844-1912) The Red Fairy Book (1890),

the last tale being “The Story of Sigurd”, in which the title character lies in ambush and kills a dragon, Fafnir.

Fafnir has a trait which would be familiar to anyone who has read The Hobbit and remembers Smaug (could you forget him?): he lies on a hoard.

This would also be familiar, of course, to anyone who knows Beowulf and, as JRRT tells us, that Old English poem was “among my most valued sources” for The Hobbit (see Letters,31). It’s interesting to note, however, that Beowulf’s dragon, though fire-breathing and covetous, like Smaug, is, in fact, mute, whereas Smaug is all-too-eloquent—as is, in fact, Fafnir, although his dialogue is limited to cursing his killer and putting a curse on his hoard, speech suggesting a further influence of The Red Fairy Book, perhaps. (Here, by the way, is a copy of The Red Fairy Book for you: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Red_Fairy_Book )

Unlike, JRRT, I’ve never had much interest in dragons and the reason may lie in my reaction to the statement I once read somewhere that “all kids love dinosaurs”. I am constitutionally averse to any statement which says things like “all x loves—or hates—y” in general, but, in this case, it’s more personal: I was one kid who never loved dinosaurs.

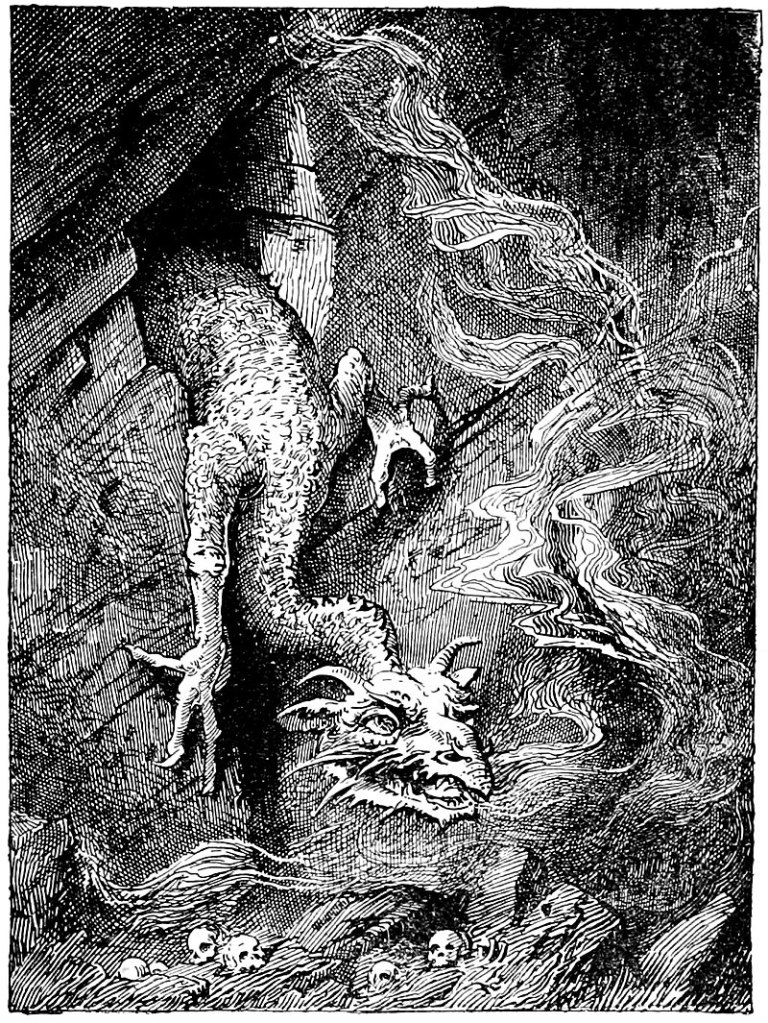

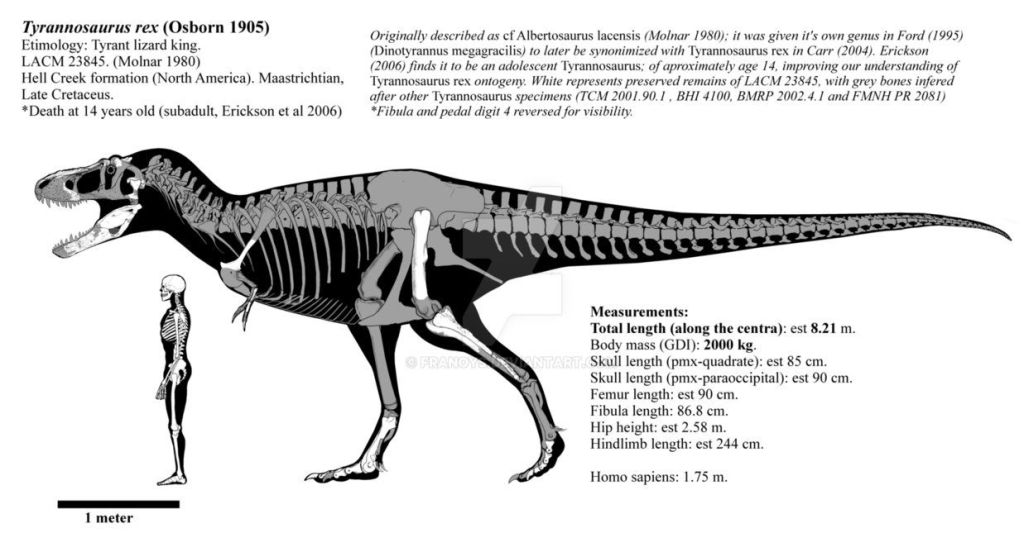

When small, I was taken to museums where very large and bony examples were on display

and yes, I would agree with whoever took me that they were very large.

(I love the original name of this one: “Albertosaurus”, which makes me imagine an Irish member of the family—“Albert O’Saurus”)

At the same time, dinosaurs seemed to me to be pretty much just that: large.

(I’m aware that there were very small ones, too, but the ones I was being shown were pointed out for their size and potential fierceness—and just look at those teeth!)

In fact, when it came to past beasts, my childhood favorite was the wooly mammoth

and once I even entered one in my school science fair, “frozen in ice” (it was an elephant model that I’d covered in glued-on hair and encased in a cardboard box covered in plastic sheeting—it didn’t win).

And maybe that’s why I’ve never been taken with dragons. (I’m probably one of the few readers/viewers of A Game of Thrones, for example, who found Daenerys’ beasts less interesting than the fencing master, Syrio Forel—who was killed much too soon.)

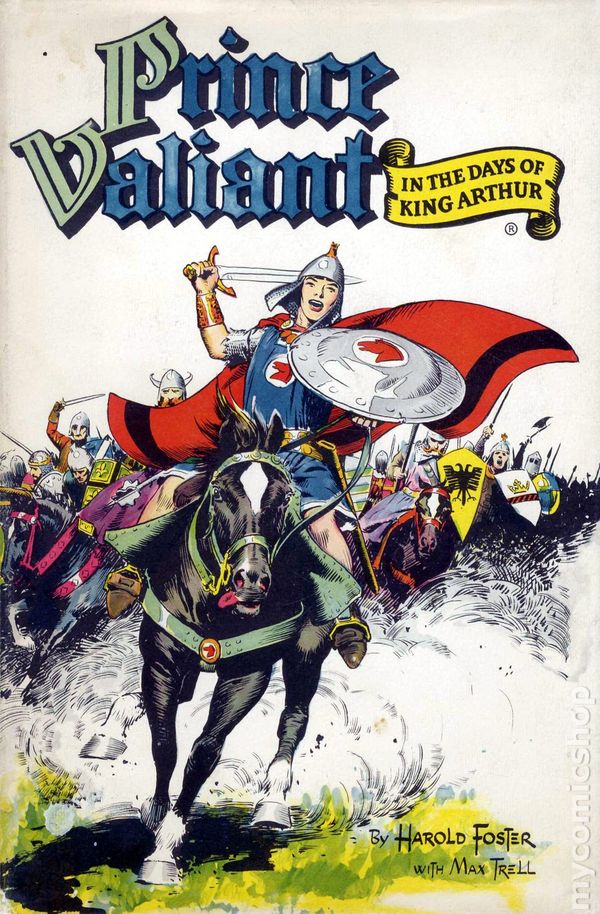

The first dragon I actually met was probably one which my childhood hero, Prince Valiant,

once fought

and, of course, this put him squarely into the St George and the dragon tradition,

(by Vittore Carpaccio, c.1465-1525)

but which is, in fact a tradition which goes all the way back to Perseus rescuing Andromeda from a sea monster

(by Piero di Cosimo, 1462-1521)

and Jason stealing the Golden Fleece from the Sleepless Dragon.

(from an Apulian krater—wine-mixing bowl—c.300BC)

All of which stories tended to make me think in terms of:

1. dragons hoard hoards and will fight to defend them

2. dragons may consume princesses or other unlucky damsels (a variant—or perhaps a commentary on a dragon’s regular diet?)

3. among their other jobs, heroes may be required to rescue princesses and exterminate said dragons, or at least steal something from them

And that was my view—or almost my view—with one exception, a short story by Kenneth Grahame (1859-1932), from his collection Dream Days (1898).

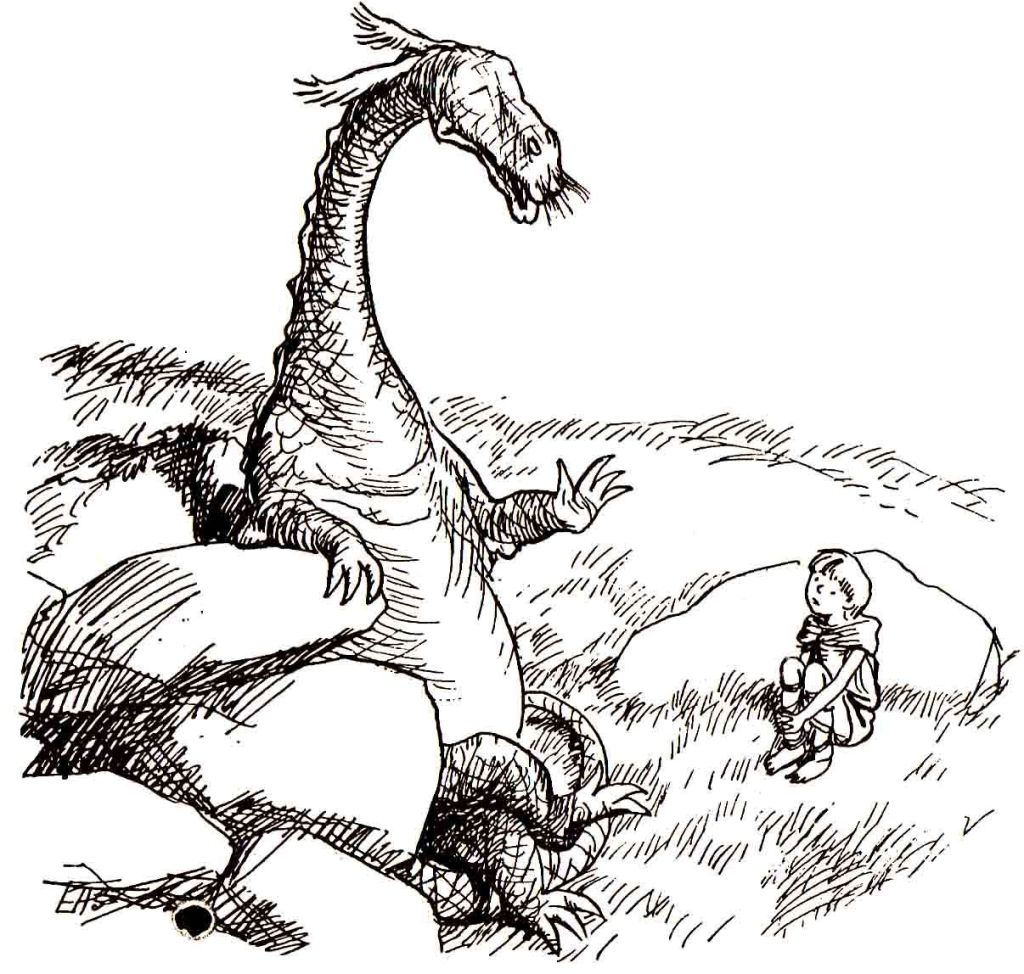

This is entitled “The Reluctant Dragon” and it concerns a boy, St. George, and a creature far from Greek mythology or Beowulf. If, like Smaug, he talks, he has no hoard, shows no desire for fire-breathing or edible royalty and is, in fact, a peaceable poet, and not in the least interested in heroes or heroics.

(If you’re a reader of The Wind in the Willows or Pooh, you’ll recognize at once that this is an illustration by E.H. Shepard. And here’s a copy of the book for you, although this is an earlier edition, with pictures by another wonderful illustrator, Maxfield Parrish: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/35187/35187-h/35187-h.htm )

This creature (nameless, in the story, which would make his publishing his poetry rather difficult, unless he was willing to be “Anon.”) has always suggested to me that there was the possibility that my limited view of dragons might be modified, given the right dragon.

Then, a few weeks ago, I was given this by one of my graduate student teaching assistants—

If you read this blog regularly, you’ve probably picked up that, among other kinds of adventure stories I read, I enjoy those set in the Napoleonic era, like the novels of Bernard Cornwell, which follow the career of an infantryman, Richard Sharpe,

or those of C.S. Forester, whose hero is Horatio Hornblower, a British naval officer.

Like Hornblower, the hero of this series, Will Laurence, is a naval officer, but his life takes a sudden shift when his ship attacks and captures a French ship carrying a very large egg: a dragon’s egg, in fact. And suddenly, we’re in an alternate Napoleonic world in which Britain, as in our history, is at war with Bonaparte, and much of the fighting takes place at sea, but there is another element: both sides have not only armies and fleets, but squadrons of dragons, and the series (there are 9 novels so far, along with a volume of short stories) follows Laurence and his dragon, Temeraire (named after a famous warship, HMS Temeraire) through a wide variety of adventures.

(A marvelous painting by Geoff Hunt—here’s his gallery—https://www.scrimshawgallery.com/product-category/prints/geoff-hunt/ )

I’ve just finished the first volume, which is mostly introductory in nature, but provides the reader with a sense of military dragons—how they’re trained, equipped, and how they’re used in aerial combat. That’s a lot to cover in one book, but the author has thought out and carefully described everything in such a way as to make this alternate almost believable—including, at the book’s conclusion, an excerpt from a late-18th century naturalist’s treatise on dragons.

So here are different dragons: non-hoarders, not hungry for the nobility, sentient and talkative, and involved in a global war between Napoleon and the nascent British Empire. I may have to rethink my feelings about dragons—but not dinosaurs.

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

Keep away from tar pits,

And remember that there’s always

MTCIDC

O