Welcome, as ever, dear readers.

Years ago, CD (the forerunner to the present creator of this blog), uploaded a posting with the same title, (see “Knowledge, Rule, Order”, 6 January, 2016 at Doubtfulsea.com), but in the intervening seven years, I’ve continued to wonder about just what those three words might mean, both consciously and unconsciously, for the original speaker of them: are they simply abstract? Or might they possibly mean something different from what that speaker intended?

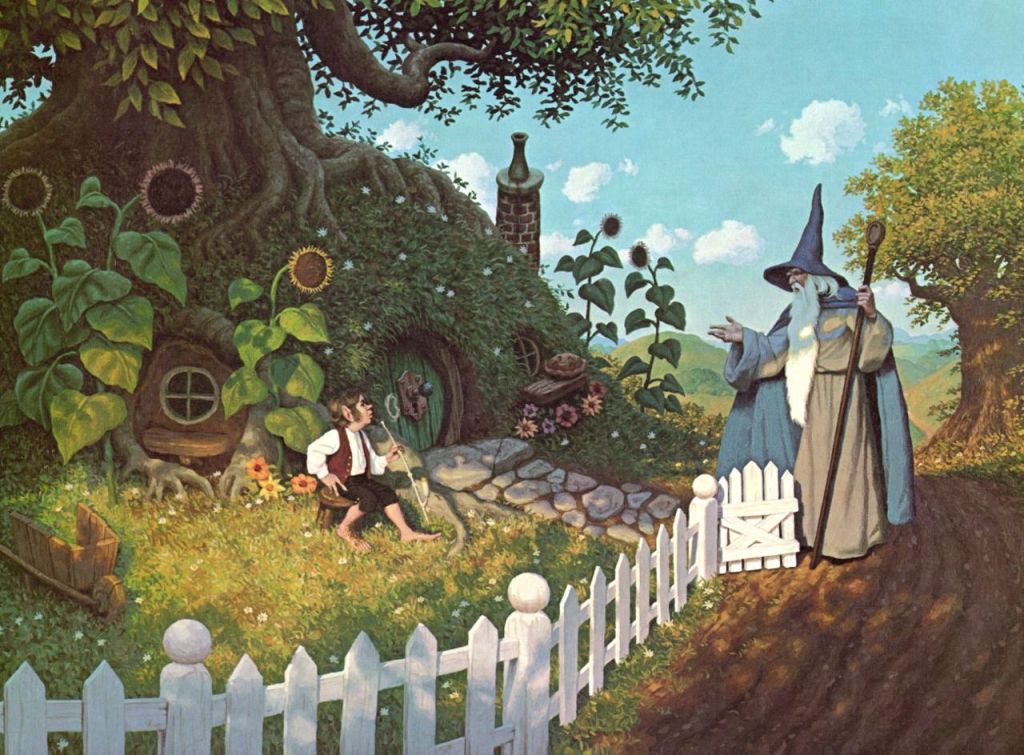

That original speaker was Saruman, who uses those three terms in his more than a little slippery attempt to persuade Gandalf into helping him to replace Sauron.

“A new Power is rising…We may join with that Power. It would be wise, Gandalf. There is hope that way…As the Power grows, its proved friends will also grow; and the Wise, such as you and I, may with patience come at last to direct its courses, to control it. We can bide our time…deploring maybe evils done by the way, but approving the high and ultimate purpose: Knowledge, Rule, Order. All the things that we have so far striven in vain to accomplish…There need not be, there would not be, any real change in our designs, only in our means.” (The Fellowship of the Rings, Book Two, Chapter 2, “The Council of Elrond”)

Gandalf will have none of this:

“Saruman…I have heard speeches of this kind before, but only in the mouths of emissaries sent from Mordor to deceive the ignorant.”

For me, this is one of the most revealing speeches in The Lord of the Rings, not only for how thoroughly it shows us the corrupted Saruman, but also for how it reflects the period when Tolkien began to write the novel, when such grand, but intentionally vague, themes or some very much like them, were in the air.

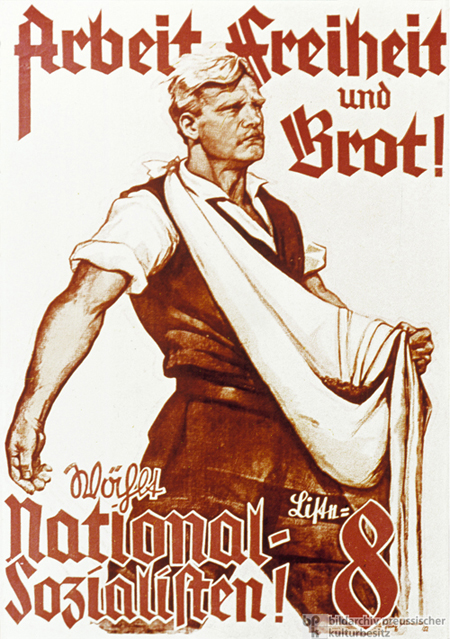

(“Work, Freedom, Bread”—for the National Socialist Party in 1928)

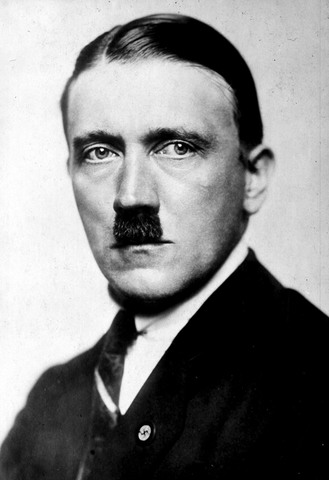

When Hitler became head of the German state in 1933,

he had learned from experience that open attempts to seize power were iffy at best, his first try, in 1923, ending in failure and an all-too-brief time in prison for him.

Subsequently, he turned to becoming a statesman, using such themes as “rebuilding Germany” to cover his real purposes.

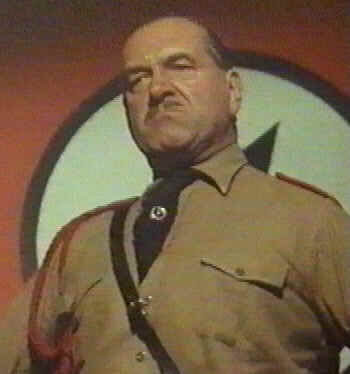

Violence was never ruled out, as we know too well, but politicking and political pressure appeared to gain him more, spawning followers and friends all over the world, as well as imitators, like the British Sir Oswald Mosley,

mocked by the comic novelist, P.G. Wodehouse (1881-1975) as Roderick Spode,

and once described by one of Wodehouse’s characters as “the amateur dictator”. Such people had definitely heard “speeches…in the mouths of emissaries sent from Mordor to deceive the ignorant” but, unlike Gandalf, had believed them and worked towards their fulfillment.

I want to begin with that first “high and ultimate purpose”: “Knowledge”.

As is well-known, Saruman’s name suggests that he was, in fact, formed to be knowing: Old English searu, upon which the name is based, means “skill/craft/cleverness” + mann, “man”, so “man of craft”.

But what is this “Knowledge” which Saruman claims has been a major goal of the Istari, the Maiar sent to Middle-earth?

Saruman himself doesn’t clarify what he means by this, which is, in this context, not surprising, but Gandalf tells us something about his past:

“…Saruman has long studied the arts of the Enemy himself, and thus we have often been able to forestall him. It was by the devices of Saruman that we drove him from Dol Guldur.”

We might also understand that he has been collecting information about Middle-earth itself, knowledge which he gathers from folk like Treebeard:

“I used to talk to him. There was a time when he was always walking about my woods. He was polite in those days, always asking my leave (at least when he met me); and always eager to listen. I told him many things that he would never have found out by himself…”

We can imagine, then, that all of Saruman’s knowledge once had been for the task for which he and the other Istari have been sent to Middle-earth: to protect it and its peoples from Sauron.

Old English searu has another meaning, however: “plot/trick/deceit”, so searumann potentially means not only “man of craft”, but also “man of deceit”. And something which Treebeard adds suggests that Saruman’s knowledge-gathering had, at some point, taken a different turn:

“…but he never repaid me in like kind. I cannot remember that he ever told me anything. And he got more and more like that; his face, as I remember it—I have not seen it for many a day—became like windows in a stone wall: windows with shutters inside.” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 4, “Treebeard”)

This simile of a stone wall might remind us of something which Treebeard said just prior to this:

“He gave up wandering about and minding the affairs of Men and Elves, some time ago—you would call it a very long time ago, and he settled down at Angrenost, or Isengard as the Men of Rohan call it.”

(the Hildebrandts)

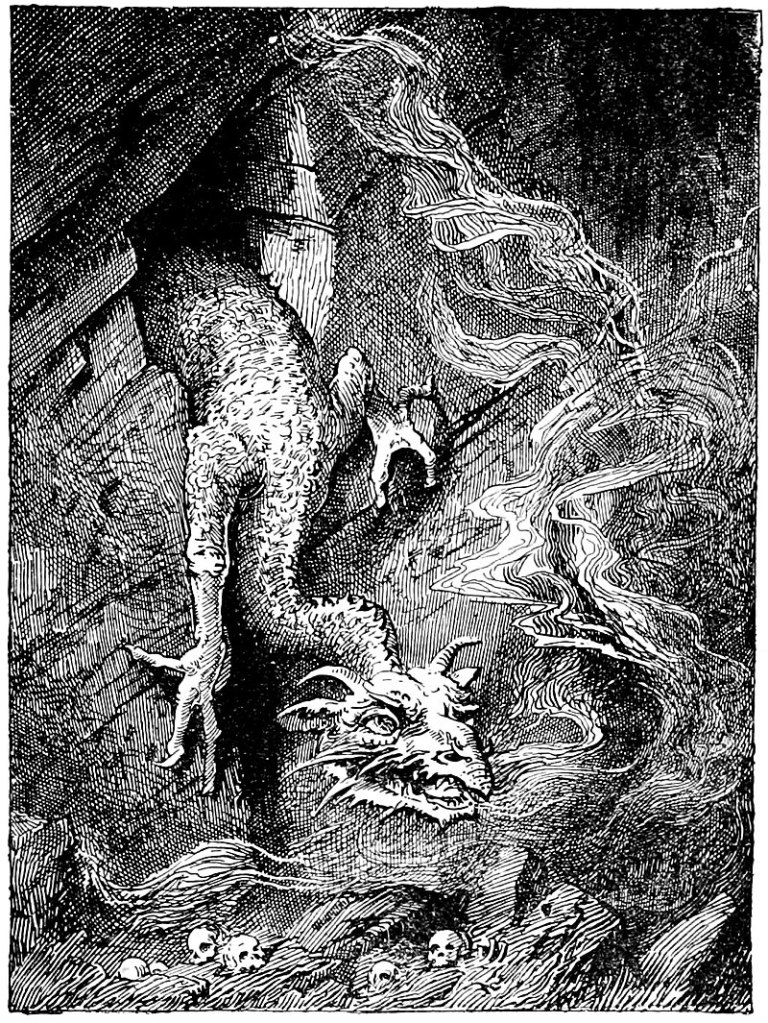

Of the five Istari,

(? I haven’t found the artist for this useful illustration.)

two disappeared to the south, leaving us with almost no information about them. The other three, Saruman, Gandalf, and Radagast, must initially have been wanderers across the north of Middle-earth, perhaps acting like the Rangers, as patrolling protectors.

It’s revealing, then, that Treebeard expresses that occupation of Isengard as giving up “wandering about and minding the affairs of Men and Elves” as those appear to have been the very things the Valar had sent him to Middle-earth to do and which suggests that, by the time he took charge of Isengard, about 250 years before the present story, Saruman was already on his way to the corruption so evident in his appeal to Gandalf.

We don’t really know when the moral rot first set in, but we can certainly understand what pushed it along: the “Orthanc-stone”, one of the palantiri, the so-called “seeing-stones”, of which one was established at Isengard and came into the hands of Saruman, much to his ruin.

(a second Hildebrandts)

The stone provided a direct connection to Sauron, and so, if nothing else, this must have sped that corruption. We have only to hear Sauron’s direction to Pippin, however:

“Tell Saruman that this dainty is not for him. I will send for it at once. Do you understand? Say just that!” (The Two Towers, Book Three, Chapter 11, “The Palantir”)

to understand that, if Saruman believes, as he assures Gandalf, that they—really he—can control Sauron, he is completely deceived. Sauron is so much the master that he doesn’t even bother dealing with Saruman directly, ordering someone he clearly believes to be a nonentity to pass a message on.

In this way we see that Saruman’s learning the ways of the Enemy has brought him too close to that very enemy, allowing the enemy to gain a knowledge of which Saruman appears to be completely unaware: a knowledge of Saruman’s own weakness—vanity, which makes him believe that only he is a “man of craft”—or, as he puts it, “the Wise”—and powerful enough to deal with Sauron. Even so, he needs help, and here we see where his quest for knowledge has ultimately taken him:

“Why not? The Ruling Ring? If we could command that, then the Power would pass to us. That is why I brought you here. For I have many eyes in my service, and I believe that you know where this precious thing now lies. Or why do the Nine ask for the Shire, and what is your business there?”

From being, as Gandalf has said, “the greatest of my order”, who had gathered great learning for the goal of countering the evil which has come into Middle-earth, he is now one who, swollen with arrogance, believes that he can use his knowledge not for the good for which he had originally employed it, but as a tool to help him to replace one form of evil with another, all the while never realizing that he has become no more than a tool himself.

As ever, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

Don’t just do no evil, but, as Gandalf would encourage us, do positive good,

And know that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O