Welcome, as ever, dear readers.

As I taught The Hobbit again this term, a student’s question from last year came back to me once more: “Where are the women?”

The answer is, aside from a few words about Bilbo’s mother, Belladonna nee Took (about whom I would love to know so much more—why was Gandalf, not, I would say, someone easily impressed–so taken with her?) and her sisters, the answer is simple: there really aren’t any. An author as fruitfully inventive as Tolkien (just look at the pile of volumes of manuscript material published by Christopher Tolkien) could easily have created some, but didn’t. And, as far as I know, he provided no explanation for this: it’s simply as much the case as Cinderella has a step-mother with two daughters.

This lack, clearly felt by Jackson & Co in their 3-part adaptation of The Hobbit, led to the stitching-in of “Tauriel”, a warrior elf,

and a subplot which, to me, caused there to be an imbalance in the story, whose original focus was upon Bilbo and his development from a Baggins who flees even from the idea of adventure—

“We are plain quiet folk and have no use for adventures. Nasty disturbing uncomfortable things! Make you late for dinner! I can’t think what anybody sees in them…” (The Hobbit, Chapter One, “An Unexpected Party”)

to someone who, in later chapters, has so changed that Gandalf, seeming to appear out of nowhere, claps him on the back and says, “Well done! Mr Baggins!…There is always more about you than anyone expects!” (The Hobbit, Chapter 16, “A Thief in the Night”)

The complications of a brief but improbable romance with a dwarf, a conflict with the king of the forest elves, and combat with sinister orcs, all take away from the author’s original intent. In the novel, Bilbo is always center stage and is meant to be and subplots of any sort can only distort and dilute the author’s intent as embodied in the text.

Women warriors, however, appear almost at the beginnings of western literature. As one of his labors,Herakles must obtain the zone (that’s “ZOE-nay”), a kind of belt, of the queen of the Amazons, Hippolyte (“hih-poh-LOO-tay”).

In Book 2 of Apollonius of Rhodes’ Argonautica, Jason, of Golden Fleece fame,

almost encounters the Amazons on his trip eastwards to Colchis (a wind blows the Argo away from their land at the last minute).

And the Athenian hero, Theseus, not only battles the Amazons,

but, in some versions of the story (there are a number of these) marries their queen, Antiope (in Greek, “ahn-tee-AH-pay”, but in English we say “an-TIE-oh-pee”)

Even Achilles is matched against the Amazons when they come to aid the Trojans and, in a dramatic moment in one version of the story, fights their leader, Penthesilea (in Greek, “pen-theh-SEE-lay-ah”, in English, “pen-theh-sih-LAY-a”) and, even as he kills her, falls in love with her.

The idea of Amazons inspired several generations of Greek sculptors and pot-painters, including the famous frieze (a sculptured band of stone) from the 5th-century temple of Apollo at Bassae (modern Greek VAH-seese).

The site was excavated in the early 19th century

and the frieze was sold to the British Museum, where it’s on display to this day.

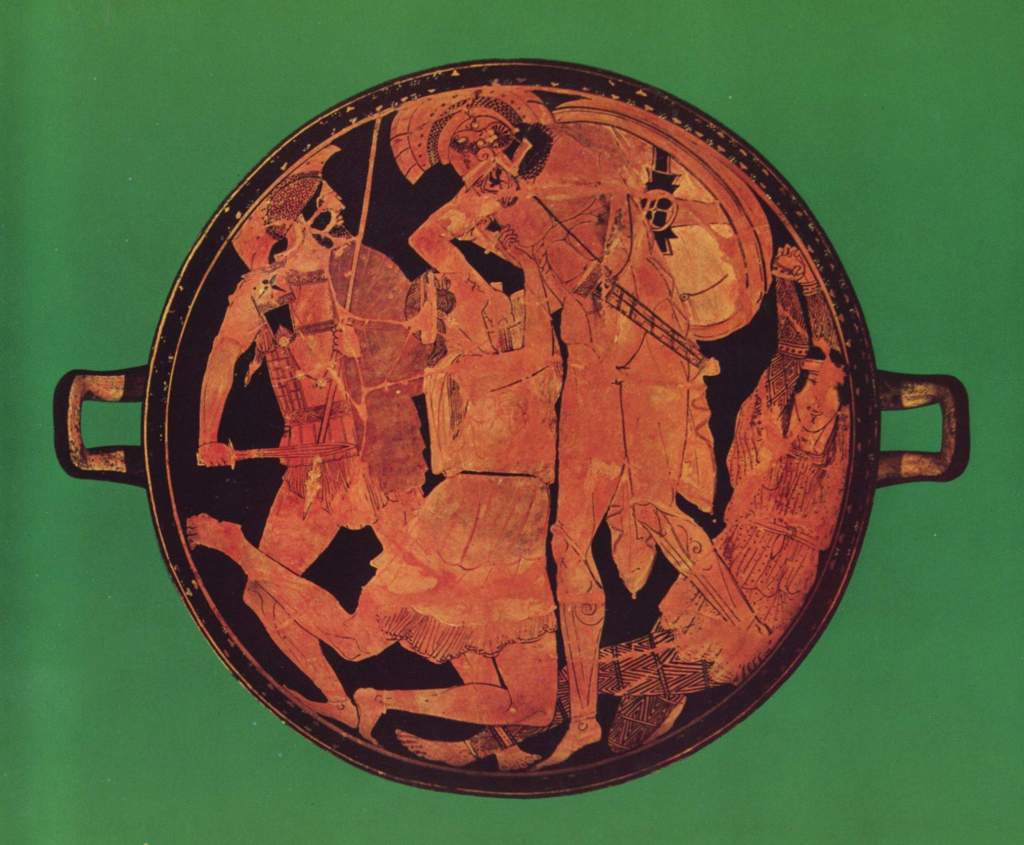

Although ancient people seemed to believe in their existence, whether there were real Amazons has been debated by scholars for years. The pot depictions, in particular, often look like, never having seen one, Athenian artists based their depictions upon the wild tribesmen they saw every day in the city, the Skythians, a horse people from north of the Black Sea,

whom the government of Athens used both as policemen and as missile troops in war,

as you can see from this depiction of Amazons fighting Greeks.

New archaeological evidence from southern Russia, however, suggests that perhaps those artists weren’t improvising, as recent finds provide the possibility that, among the Skythians, woman warriors were part of the culture. (See, for example, this CNN piece from January, 2020: https://www.cnn.com/2020/01/06/world/scythian-amazon-burial-scn-intl-scli/index.html )

If there was no woman warrior like “Tauriel” in The Hobbit, there is certainly one in The Lord of the Rings and, in fact, there were almost two.

Those of us who are readers of the text have always known and loved Eowyn and that amazing scene in The Return of the King (Book Five, Chapter 6)—but, pictures are (almost) better than words here—

Somewhere in the scripting of The Lord of the Rings, a combat role had been given to another woman: Arwen and some scenes were actually filmed. Here’s a rough image—

As in the case of “Tauriel”, I can understand the temptation: in the book, Arwen seems a very passive figure, at best sending Aragorn a banner she has sewn for him:

“ ‘It is a gift that I bring you from the Lady of Rivendell,’ answered Halbarad. ‘She wrought it in secret, and long was its making.’ “ (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 2, “The Passing of the Grey Company”)

(This is a 1911 painting by Sir Edmund Leighton, 1852-1922, which has had various titles, including “Stitching the Banner”. I’ve used Leighton paintings before, generally classical scenes, for which he was famous, but I was directed to this work from the Wiki entry for “Arwen”, which had this, by Anna Kulisz, which credited its origin to the Leighton.)

And making only a kind of traditional story-book last appearance, to marry him.

The script writers had already changed the text, removing Glorfindel, and putting Arwen on his horse, Asfaloth.

As well, it’s not Frodo alone who crosses the ford of the Bruinen and turns back to defy the Nazgul, it’s Arwen,

who then calls up the water to wash them away, which was done by Elrond and Gandalf in the book (The Fellowship of the Ring, Book Two, Chapter 1, “Many Meetings”)

(A powerful illustration by John Howe)

In the second film, this was to be expanded by having her bring the reforged sword, Anduril, to Aragorn at Helm’s Deep and to join in the fighting there, but for reasons I have so far seen no documentary evidence for—possibly a very loud fan revolt?—that idea was scrapped. And I’m glad that it was, for the same reason that I believe that the introduction of “Tauriel” was not a good choice. Everything we know up to this point in the story about Eowyn has led us logically to the moment of her confrontation with the Nazgul: a “Shield-maiden”, frustrated at always being left behind, in despair at the thought of Aragorn’s imagined death on the Paths of the Dead, conspiring with Merry though both have been ordered to stay behind, it seems completely natural that she would face the chief of the Nazgul over her uncle’s body. To have a parallel in Arwen would be to seriously dilute the impact of that scene, especially in that it’s clear that Eowyn has not planned to return from the relief of Minas Tirith. As Merry sees her at the moment of facing the Nazgul:

“Eowyn it was, and Dernhelm also. For into Merry’s mind flashed the memory of the face that he saw at the riding from Dunharrow: the face of one that goes seeking death, having no hope.” (The Return of the King, Book Five, Chapter 6, “The Battle of the Pelennor Fields”)

I know that this relegates Arwen to the lesser position she actually holds in The Lord of the Rings, but I would prefer that to losing the full impact of this—

Thanks, as always, for reading,

Stay well,

And remember that, as ever, there’s

MTCIDC,

O