Welcome, dear readers, as always.

Recently, I read a very detailed essay from 2012 by Michael Livingston, entitled, “The Myths of the Author: Tolkien and the Medieval Origins of the Word Hobbit”, which you can read here: https://dc.swosu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1130&context=mythlore in which he reviews the various past theories for the discovery/invention of the word. I, for one, have always been perfectly willing to believe JRRT’s “it came out of the blue”—almost in an act of creative self-defense when he was chained to correcting what must have seemed like an endless series of student essays (as a professor, I can empathize—does this distort my judgment?). In general, it’s clear that JRRT had a Muse to prompt him, perhaps especially when he felt mired in quotidian tasks. And yet, reading Livingston’s essay, I began to wonder, especially after referring to two Tolkien letters.

In 1938, Tolkien had been asked about the word “hobbit”, when someone signing him/herself “Habit”, published a review of The Hobbit in The Observer, referring to “little furry men” spotted in Africa and mentioning that a friend had a memory of “an old fairy tale called ‘The Hobbit’ in a collection read about 1904’. Tolkien’s reply at the time was brief: “I have no waking recollection of furry pygmies…nor of any Hobbit bogey in print by 1904…” (letter to The Observer, 20 February, 1938)

Tolkien returned to this review, however, in a 1971 letter to Roger Lancelyn Green:

“Habit asserted that a friend claimed to have read, about 20 years earlier (sc. c.1918) an old ‘fairy story’ (in a collection of such tales) called The Hobbit, though the creature was very ‘frightening’… I think it is probable that the friend’s memory was inaccurate (after 20 years), and the creature probably had a name of the Hobberd, Hobbaty class.” (letter to Roger Lancelyn Green, 8 January, 1971, Letters, 571)

“Hobbit bogey” seems like rather a strange term—a “bogey” is a kind of demonic spirit (the origin of the English—actually, Scots—verb “to boggle”—for more on “to boggle”, see: “Spooked”, 2 February, 2022 at this blog). And, in this same second letter in which he refers to “Hobberd” and “Hobbaty”, he also mentions “Hobberdy Dick”—what’s all this about?

Livingston, in his article, cites the work of several earlier scholars, including Donald O’Brien’s “On the Origin of the Name ‘Hobbit’” (Mythlore 16.2, No.60, 1989, 32-28—which you can read here: https://dc.swosu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2675&context=mythlore ), and Gilliver, Marshall, and Weiner, The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary, OUP, 2006, in both of which the Denham Tracts are named. Who was Denham? What was Denham? And how might he have influenced JRRT?

Let’s go back a step or two.

Even though he’s more of a dashing grave robber than a scientist, when we—or maybe just I?—think “archaeologist”, the first name which comes to mind is “Indiana Jones”.

The second is Sir Arthur Evans.

The major difference between the two isn’t, of course, that the one is fictional, but that a real archeologist, like Evans, directs patient excavation and documentation at a site, something which can take years and maybe not be completed in the lifetime of that first director (Evans worked at his site, Knossos, from 1900-1913, then again from 1922-1931 and it’s still being worked on today.)

During Evans’ lifetime—and that of Indiana Jones’ (1899-1993?) early years–the modern science of archaeology was only gradually being created, being descended most recently from something called “antiquarianism”.

Long before there were professional archaeologists, antiquaries looked into the past. In England, although the occasional medieval or renaissance scholar might be curious about the past, the real beginnings are with the rise of the age of science, beginning in the later 17th century. Many of these men were clergy, a good example being William Stukeley (1687-1765),

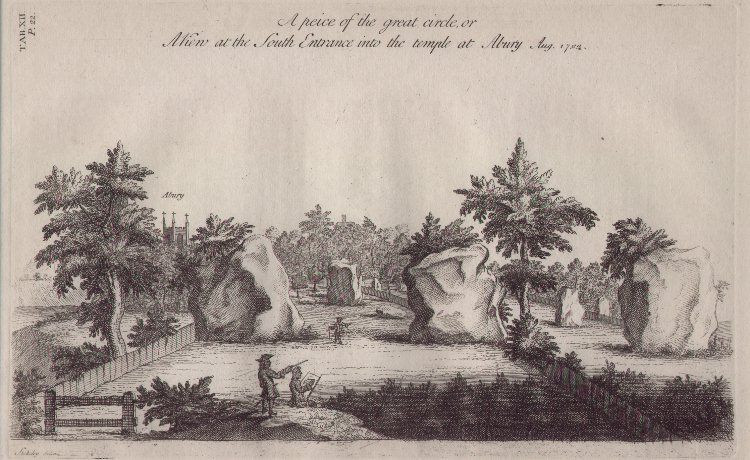

who was interested, among other things, in stone circles, like Stonehenge

and Avebury.

These are engravings from Stukeley’s own illustrations—here are modern views for an interesting contrast—

Unfortunately for science, Stukeley’s ideas about these places were less than scientific and he began to see them as:

1. druidic monuments—and, worse, that druids were monotheistic semi-Christians

2. and places like Stonehenge and Avebury were actually proto-Christian sites (for more on this, see: Stukeley, Stonehenge A Temple Restor’d to the British Druids, 1740, https://archive.org/details/b30448554/page/n7/mode/2up and Abury A Temple of the British Druids, 1743, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/64626/64626-h/64626-h.htm For all of this sort of thing, Stukeley also had a more scientific side, visiting many sites—not easy to do in early-18th-century England, when travel by road was difficult, at best—carefully measuring things and thinking stratigraphically. Because of his work, we also know much more about ancient monuments which have not survived or have suffered damage over time. In fact, he’s quite admirable in his way and Stuart Piggott, his modern biographer, has given us a detailed portrait of him in William Stukeley An Eighteenth-Century Antiquary

which, if like me, you’re interested in the history of archaeology, I would recommend.)

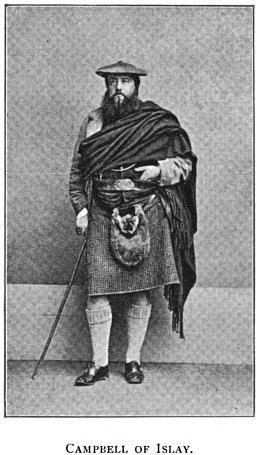

Antiquaries were not just proto-archaeologists, however, but also proto-folklorists/anthropologists and, as many were clergymen, it was natural to collect from their parishioners everything from folksongs, folktales, and folklore to local vocabulary. If such collecting had many devotees among the clergy in the UK, ordinary people might also be involved. One such was John Francis Campbell (1821-1885),

with his Popular Tales of the West Highlands, 1860-2, which you can read here: https://archive.org/details/populartalesofwe01campuoft/page/n5/mode/2up (Vol.1); https://archive.org/details/cu31924080788676/page/n9/mode/2up (Vol.2); https://archive.org/details/populartalesofwe00campuoft/page/n5/mode/2up (Vol.3); https://archive.org/details/populartalesofwe04camp_0/page/n7/mode/2up (Vol.4)

Another was Michael Aislabie Denham (1801-1859), who, from 1846 to 1858, produced a series of works with titles like A Collection of Proverbs and Popular Sayings relating to the Seasons, the Weather, and Agricultural Pursuits, gathered chiefly from oral tradition. These are monographs, some brief, some longer, which were originally printed in small numbers (50 copies, generally), but which were eventually collected and reprinted in two volumes in 1892/95 which you can read for yourself here: https://archive.org/details/cu31924092530504/page/n7/mode/2up (Vol.1); https://archive.org/details/denhamtractscoll00denh/page/n7/mode/2up (Vol.2)

Something in Volume 2 might link Tolkien to Denham.

“Hobberd, Hobbaty”, and “Hobberdy Dick” all have that “Hob” and, by employing the index to those tracts, we find, in a long list of supernatural creatures: “hob-goblins, hobhoulards…hob-thrusts…hob-thrushes…hob-and-lanthorns…hob-headlesses…hobbits…hobgoblins…” (Denham Tracts, Vol.2, 77-79)

“Hobbits?”

If you are skeptical, Livingston himself admits that there’s no hard evidence, at the moment, that Tolkien had ever opened that 2-volume collection—although Gilliver et al. note that there were copies available in Oxford libraries—but the fact that JRRT mentions other “hobs” in his letter to Green and they, in the list in the Tract, are associated with “hobbit” might suggest that, although he may have long before picked up the word in his reading (we know that he enjoyed folklore) without even remembering that he had done so. Or, as I had always before believed, had “hobbit” had simply come to him, as he told us, and not only the hobbit, but his home and, in the sentences following, his people and their culture, from pure inspiration (with a touch of desperation)? For myself, I’ll stick with the Muse.

As always, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

Always cite your sources (unless your inspiration comes from the Muse, in which case, offer a sacrifice),

And, as well, remember that there’s always

MTCIDC

O

ps

Stukeley’s enthusiasms could have gotten him into scholarly trouble when he was deceived into believing that Charles Bertram’s medieval forgery, The Description of Britain by “Richard of Cirencester”, was authentic. Fortunately for him, although there were some early doubts, the truth about this fake didn’t come out until a century after Stukeley’s death. You can read more about this at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Bertram You can read the 1809 translation of this forgery at: https://archive.org/details/descriptionofbri00bert/page/n7/mode/2up and read the series of articles from 1866-7, by the splendidly-named Bernard Bolingbroke Woodward, which revealed the work as a forgery here:

https://archive.org/details/sim_gentlemans-magazine_january-june-1866_220/page/300/mode/2up (Parts 1 &2)

https://archive.org/details/gentlemansmagazi221hatt/page/458/mode/2up (Part 3)

https://archive.org/details/sim_gentlemans-magazine_1867-10_223/page/442/mode/2up (Part 4)

pps

Not only could antiquarianism be the target of fraud: it could also be the target of mockery. See Charles Dickens’ The Pickwick Papers, 1837, Chapter XI, “Involving Another Journey, And An Antiquarian Discovery…” which you can read here: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/580/580-h/580-h.htm#link2HCH0011

ppps

I admit to a small literary borrowing, by the way: “hobbit-forming” was something which turns up in a Tolkien letter, but, looking through them, I can’t seem to find where. Tolkien is actually quoting someone else, so I guess I need to admit to a double-borrowing!