Welcome, as ever, dear readers.

Occasionally, I’ve done a film review, but they’ve commonly been of Star Wars or Tolkien-themed shows. Yesterday, however, I went to see the new Napoleon film and I want to think aloud a bit about it.

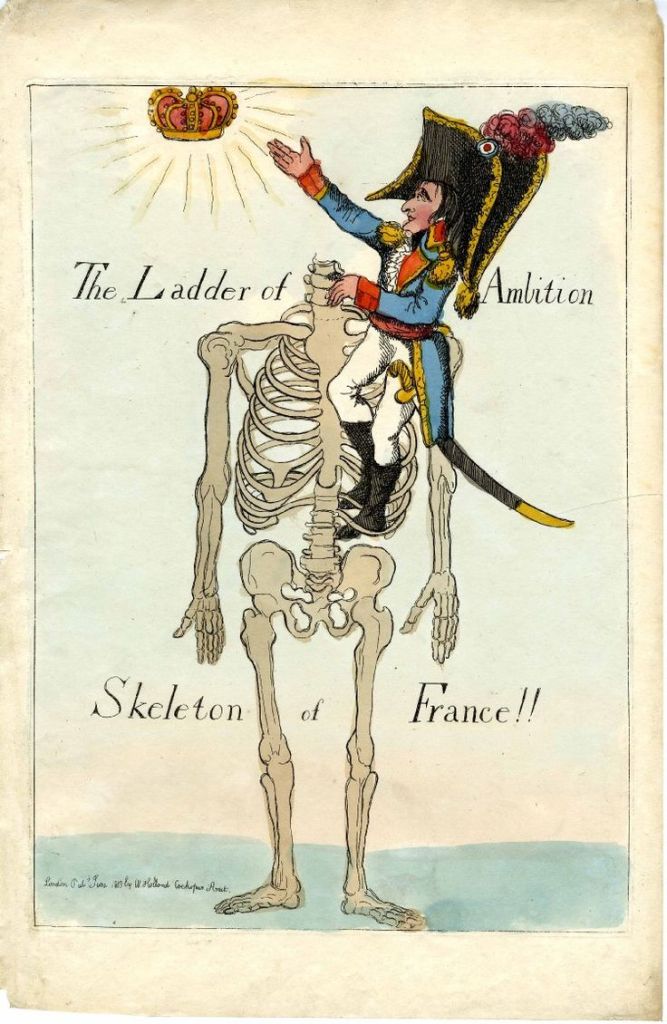

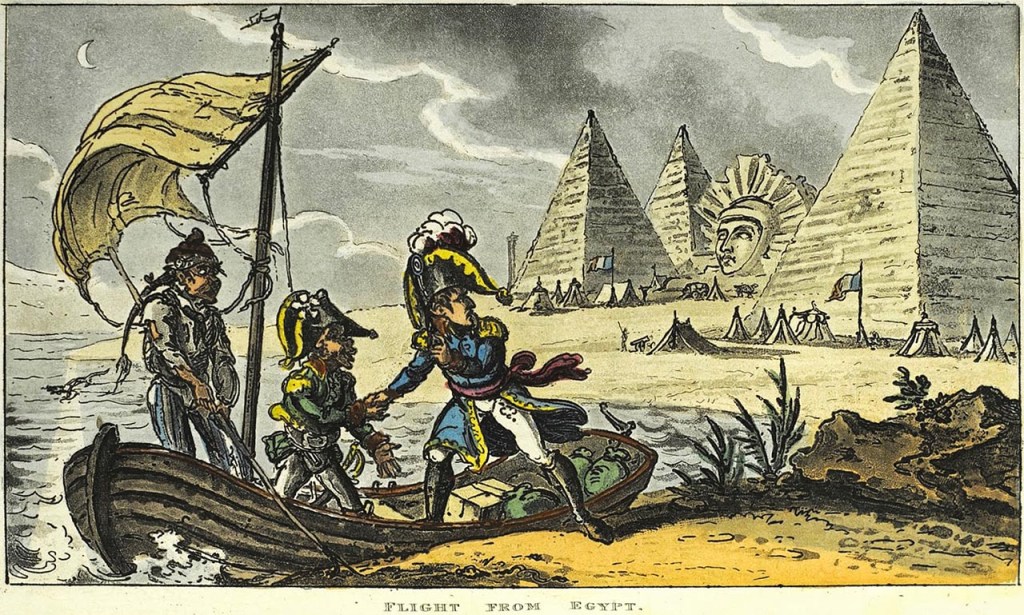

If you read this blog regularly, you know that I really dislike the levels of hatred and abuse which can be found on every level of the internet and, when such is applied to film, a review which employs them is, to me, useless. It might tell me what the reviewer didn’t enjoy, but it doesn’t really enlighten me as to the film itself. In my reviews, I try to understand what the creators were attempting to do and, in my opinion, whether they succeeded. In the case of this new film, much of the anger, etc., has been directed at its lack of historical accuracy and that’s true. The four battle scenes: Toulon (1793), Austerlitz (1805), Borodino (1812), and Waterloo (1815), although given the correct date on the screen, have virtually nothing to do with the actual events. Instead, they seem like fables about the brutal violence behind Napoleon’s “glory” and, though this isn’t underlined in the film, it’s clear that Napoleon’s rise is just as this period caricature shows it to be—

Still, in a film which goes to such lengths to look like the time in which it takes place (the costume designers should definitely be handed awards, and the sets are impressive), history does have a place. Napoleon’s self-coronation, for instance, really captures something of the grandeur which David created in his depiction of it.

(Napoleon, instead of being crowned by Pope Pius VII, crowned himself, then turned and crowned Josephine, as in the painting. What wasn’t in David’s original sketches was the Pope raising his hand in a traditional blessing. Napoleon, as usual, micromanaging, saw that the Pope’s right hand was in his lap and told David to redraw it.)

But, for me, the real problem lies in the title of this posting, which is a term by which the English, who feared and hated Napoleon at the same time, sometimes referred to him.

(There are dozens and dozens of different English caricatures of Napoleon throughout his entire life and career, depicting him as everything from a dwarfish sword-waver to a crocodile. Here’s an illustrated article on the subject—with a mild parental guidance warning: https://www.danceshistoricalmiscellany.com/corsican-monster-british-caricature/ )

By “monster”, the British meant a kind of demonic figure, sometimes, in caricatures, linked with Satan,

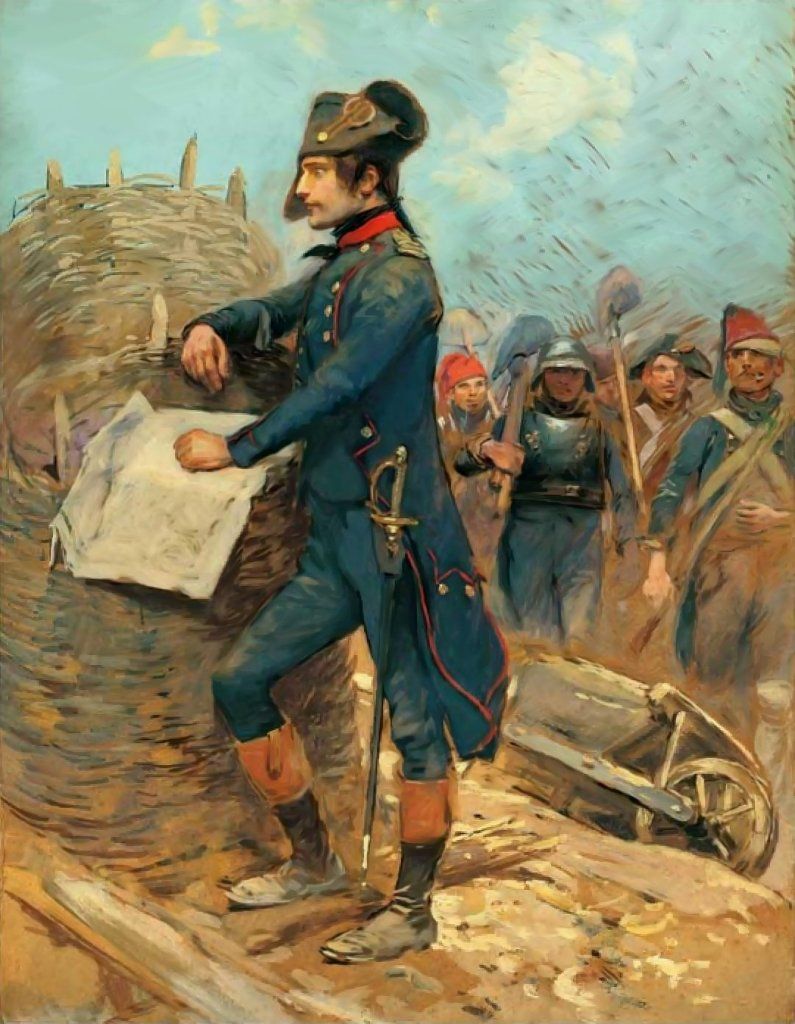

but, when it has come to film-making, it seems that his active career, which we might see as from his victory at Toulon in 1793

(by Edouard Detaille—one of my favorite late 19th-early-20th century military artists)

to his second and final exile on St. Helena, where he died in 1821,

was so full of events, that the Monster was, in fact, a monstrosity, an almost impossible thing to capture on film—although not for want of trying. An incomplete list of films—fictional, not including things like documentaries—set in, or about, the Napoleonic era in general on WIKI runs from 1912 to 2018 and has several hundred (I stopped counting in 1950, when there are already over one hundred) entries. (Here’s the link—see how far you get: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Napoleonic_Wars_films )

As for films about Napoleon himself, this is a complex picture, part of it covered by this article: https://www.vulture.com/article/napoleon-movies-history.html , but just a quick pass through the material underlines my point: the difficulty of somehow compressing a life full of events into something which won’t give an audience what Ridley Scott, in an interview, called “bum ache”.

The first known film in which Napoleon appears certainly wouldn’t have afflicted anyone, being a short, by Louis Lumiere, in 1897 (42 seconds). After that there followed, in 1908-9, two films from the same studio, Vitagraph, “Napoleon, the Man of Destiny” and “The Life Drama of Napoleon Bonaparte and Empress Josephine of France”, which appear to have been combined into one, “Incidents in the Life of Napoleon and Josephine”—here’s the YouTube version: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zmnHQbrh3KY (This is from the site of the very knowledgeable Clark Holloway.) “Incidents” it is, being only about 25 minutes long.

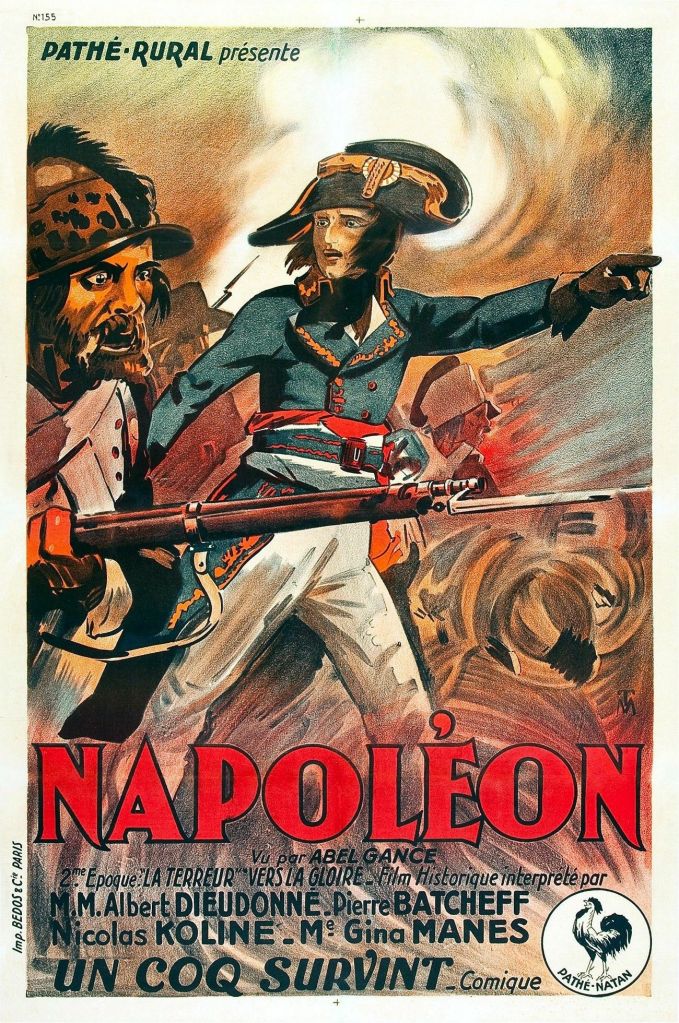

After this comes Abel Gance’s (1889-1981) Napoleon, 1927, whose production history illustrates my point.

Gance intended a full-scale film biography in 6 parts. The director’s definitive cut of the first part lasted for 9 hours and 40 minutes. No other parts were ever made and the film languished mostly in notoriety until the product of a process of reconstruction in 1979 produced a 4-hour version, then a 5-hour version. (You can read the fascinating history of the whole project, from Gance’s original, here: https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/features/monumental-reckoning-how-abel-gances-napoleon-was-restored-full-glory ) And Gance’s first part went no further than Napoleon’s first reaching Italy, in 1796.

Although there were further attempts at the big picture, like Sasha Guitry’s Napoleon, 1955, (you can see it here in the US dubbed version: https://archive.org/details/Napoleon_ )–at two hours, you can imagine how little that big picture was—

film-makers also tried other approaches, much smaller and more domestic, such as the 1937 Conquest, about Napoleon’s affair with the Polish countess and nationalist, Maria Walewska (1786-1817).

And here we see the idea of Napoleon the romantic (if not womanizer, which was probably closer to the truth), which forms one half of the plot of Scott’s Napoleon. As the screenwriter, David Scarpa, explains:

“So [Ridley] wants to know what you’re going to bring to it, what your point of view on it is. It was an almost impossible story to tell just in terms of the sheer sprawl of what Napoleon had done and his influence on European history and 45 battles fought and essentially writing the Code Napoleon, which is the basis of much of continental European society. So it would be almost impossible to tell the definitive version of that story within two and a half hours. And what I found myself most intrigued by was this little vignette in the book about his relationship with Josephine, his wife.” (You can read the whole interview here: https://www.msn.com/en-us/movies/news/ridley-scotts-napoleon-writer-david-scarpa-explains-whats-true-and-false/ar-AA1kTqd1 )

So, in two-and-a-half hours, we’re shown, in very brief form, Napoleon’s life, from 1793 (although the first date shown is 1789, along with the execution of Marie Antoinette, which actually took place on the 16th of October, 1793),

to his death on St. Helena in 1821, intertwined with his complex relationship with Josephine. He first meets Josephine at a party, after his success at Toulon, in 1793, where he stares at her until she comes up and inquires as to why he’s staring, which he fumblingly first denies, then admits. And the story goes on from there. It seems to me that there are two big dangers here:

1. the relationship story will overwhelm the biography and the real title of the film should be “Josephine—and Napoleon”

2. the appeal of this relationship relies upon the two principal characters—are they at least believable, if not likeable?

To the first, I would say that this was more-or-less successful, in my opinion. There was a balance between the two and I rarely felt that Napoleon’s private life was overwhelming his public life—although the idea that Napoleon abandoned his 1798 Egyptian campaign to return to France just because it was rumored that Josephine was having an affair is stretching things a bit.

To the second, I admit that I wasn’t convinced.

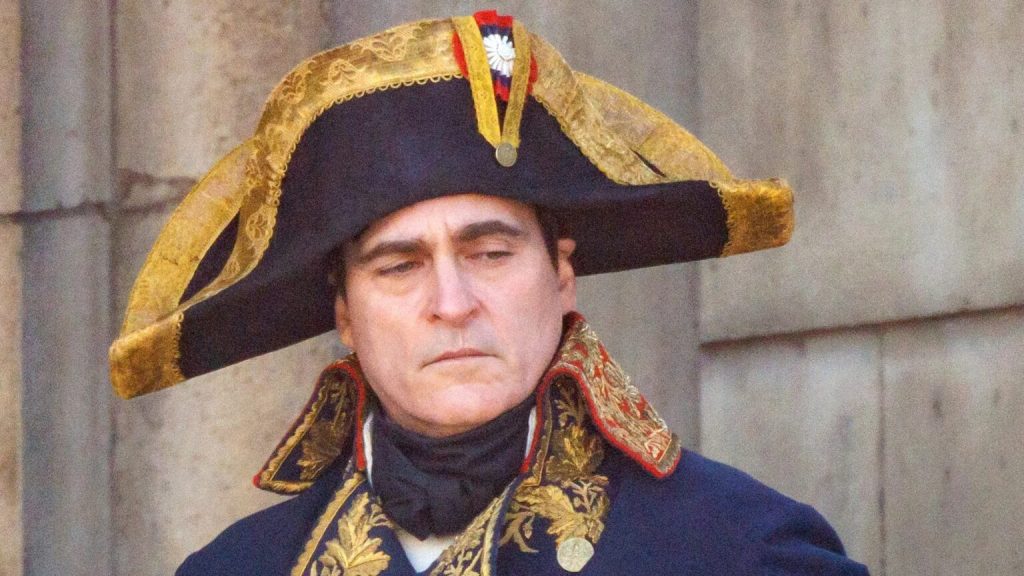

Part of the problem, for me, was that Joaquin Phoenix, Napoleon, seemed to me to be miscast, playing the role as if he were a sometimes rather pathetic middle-aged Mafia boss (it didn’t help that his flat American accent and delivery were surrounded mostly by British actors, including the woman who played Josephine—and there was a laugh in the theatre when he turned on the British ambassador and shouted in that flat accent, “You think you’re so great, ‘cause you got boats!”). As well, for much of the movie, he was simply physically too old, Napoleon at the time of his success at Toulon in 1793 was in his early 20s, having been born in 1769. One has only to see David’s unfinished portrait of him from about 1797 to see what he must really have looked like at the time.

versus

Phoenix never seems to be young and as daring and lively as the real man must have been in his first years, but is already simply stodgy, even at times with Josephine. It’s no wonder that, initially, she seems to be thinking about him as a kind of social investment, rather than as a potential BF and, in their physical encounters, she continues to be detached, even when we’re being told that this has become a powerful, if complex relationship. I’m aware that the script writer wanted to show what might be a paradox: the active, intense general/statesman, on the one hand, but the clumsy and mostly unromantic husband on the other:

“the idea of a man who is profoundly capable and competent in the realm of battle, and yet profoundly incapable and incompetent in the realm of love, in the realm of human relationships, and how those two things play off of one another.”

The difficulty for me is that we seem to be told, at the same time, that there was passion at the base of this, but, apart from a couple of tearful moments, I don’t feel that I was ever shown that in a meaningful way. She seemed too passive and he too bullish.

So, would I recommend this film? Without hedging, I guess that I would say the following:

1. if you’re a military history buff and know something about this period, you probably will spend a certain amount of time shaking your head (wondering, for instance, why the British and French are fighting from entrenchments at Waterloo and why the Prussians appear on the battlefield from the wrong direction)

2. if you want to see another side of a World Conqueror, this is definitely a start, but don’t expect too much—behind this film are letters exchanged between Napoleon and Josephine and they have their passionate moments, but, as read in a flat voice by an off-screen Phoenix, I kept wishing that this is what the writer and director would have shown me, rather than narrated at me.

At the same time, as always, I would say that viewers, like reviewers, often have very different opinions and, if anything I’ve written sparks your interest, go see it for yourself.

Thanks, as ever, for reading.

Stay well,

Avoid Waterloo at all costs,

And know that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

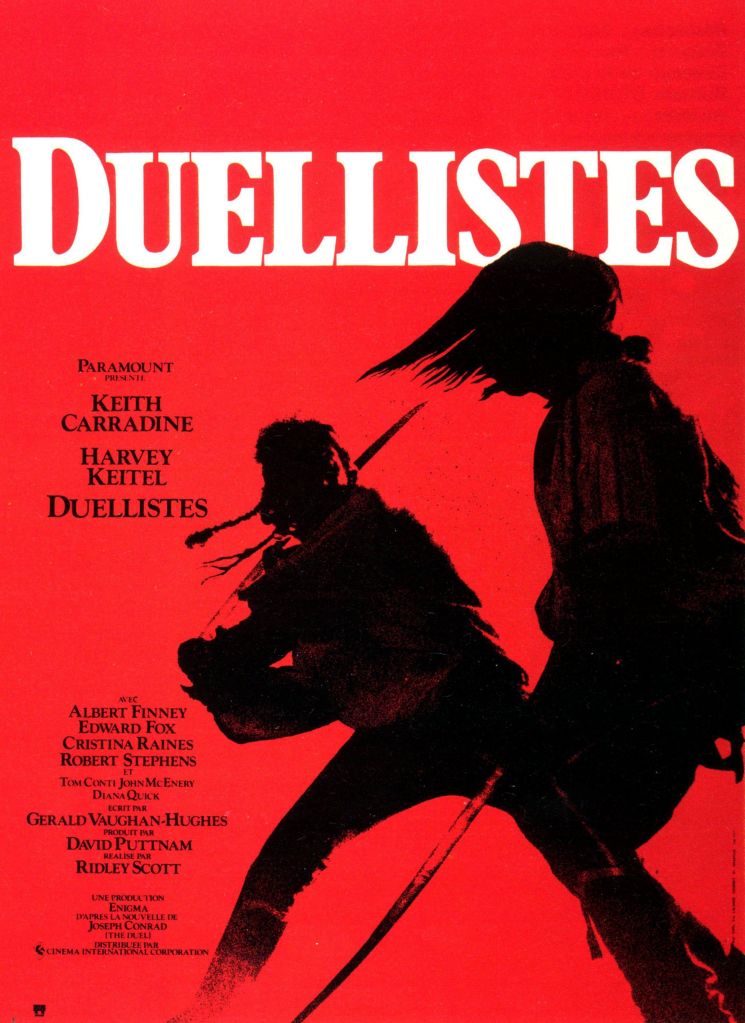

While I might have mixed reactions to this film, I whole-heartedly recommend Ridley Scott’s much earlier (1977) Napoleonic film, The Duellists, which is a little jewel.

It’s based upon a short story by Joseph Conrad, “The Duel”, which you can read here: https://archive.org/details/asetsix00conrgoog/page/n6/mode/2up