As ever, dear readers, welcome.

The English language has many challenges for those learning it—pronunciation vs spelling is a big one, but another is caused by a linguistic feature called ablaut. You see it in some nouns, where a change in spelling can cause a change in meaning, as in foot/feet and woman/women, where even the pronunciation changes. It also occurs in verbs and, sometimes, it can seem pretty spectacular, as in some old verbs, like smite/smote/smitten and slay/slew/slain.

This brings me to creep. Is it creep/creeped/creeped? No—it’s creep/crept/crept. But then there’s the expression which forms the title of this posting.

If you go browsing the various etymological sites, like Etymonline (https://www.etymonline.com/word/creep) or the now defunct (isn’t that a great word? from Latin defungor, “to finish/have done with something”, used euphemistically of the dead) The Word Detective (http://word-detective.com/2011/09/the-creeps/ ), you find that the basic idea is that, if you’re spooked (another great word, seemingly in English from Dutch spook, “ghost”—and there’s the Swedish spoeke, “scarecrow”, which can really spook you out—for how this is said in Swedish, see: https://en.glosbe.com/en/sv/scarecrow )

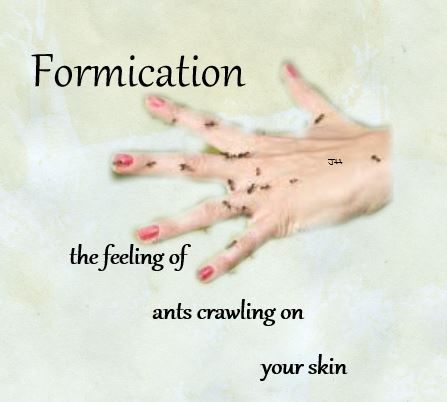

it’s as if you can feel something crawling across your skin. (A medical term for this is formication, from Latin formica, “ant” and a very vivid term it is, too!)

It’s Halloween time again (not “Holloween”, although I hear that all the time—see the posting “Holloween”, 5 February, 2020, for more) and, although things can spook us during the year, this season, when according to ancient Western belief, the doors between the worlds lie open and the dead may return, is particularly rich in weirdiosity (from Old English wyrd, meaning, among other things, “fate” plus Latin –osus, “full of” plus Latin –itas, which creates an abstract noun). In other words, more creeps us out.

For me, it’s usually not the obvious—

although, given a darkened movie theatre or living room late at night, I wouldn’t say that I felt completely safe in the parking lot afterwards or going to the kitchen for a snack—but it’s more the implied which makes me look over my shoulder in dim places.

For an example, take M.R. James’ (1862-1936)

(Dr. Montague Rhodes James was actually a prominent member of the English academic community, hence the gown.)

short story, “Oh, Whistle and I’ll Come to You, My Lad” from his 1904 collection, Ghost Stories of an Antiquary.

The title comes from a lyric by Robert Burns to a slightly older tune, the lyric beginning with the chorus:

“O, whistle, and I’ll come to you, my lad;

O, whistle, and I’ll come to you, my lad;

Tho’ father, and mother, and a’ should gae mad,

O, whistle, and I’ll come to you, my lad.”

(You can read the rest here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oh,_whistle_and_I%27ll_come_to_you,_my_lad and hear a lovely performance by the Canadian mezzo, Patricia Hammond, here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=542RhM5K9mI )

This seems like the opening of something rather gentle, but that title is typical of a James story, just as he describes:

“Two ingredients most valuable in the concocting of a ghost story are, to me, the atmosphere and the nicely managed crescendo. … Let us, then, be introduced to the actors in a placid way; let us see them going about their ordinary business, undisturbed by forebodings, pleased with their surroundings; and into this calm environment let the ominous thing put out its head, unobtrusively at first, and then more insistently, until it holds the stage.” (originally in V.H. Collins, Ghosts and Marvels, 1924, quoted in the M.R. James Wiki article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M._R._James )

This story begins at dinner in a Cambridge University college. Professor Parkins announces that he’s going to the seaside to work and to play golf at a local course. (It’s called “Burnstow” in the story, but is actually Felixstowe—

which does have a golf course, the Felixstowe Ferry Golf Club being the fifth oldest in England.)

Another (unnamed) faculty member casually asks him to check the site of the “Templars’ preceptory” there to see if it’s worth excavating the following summer.

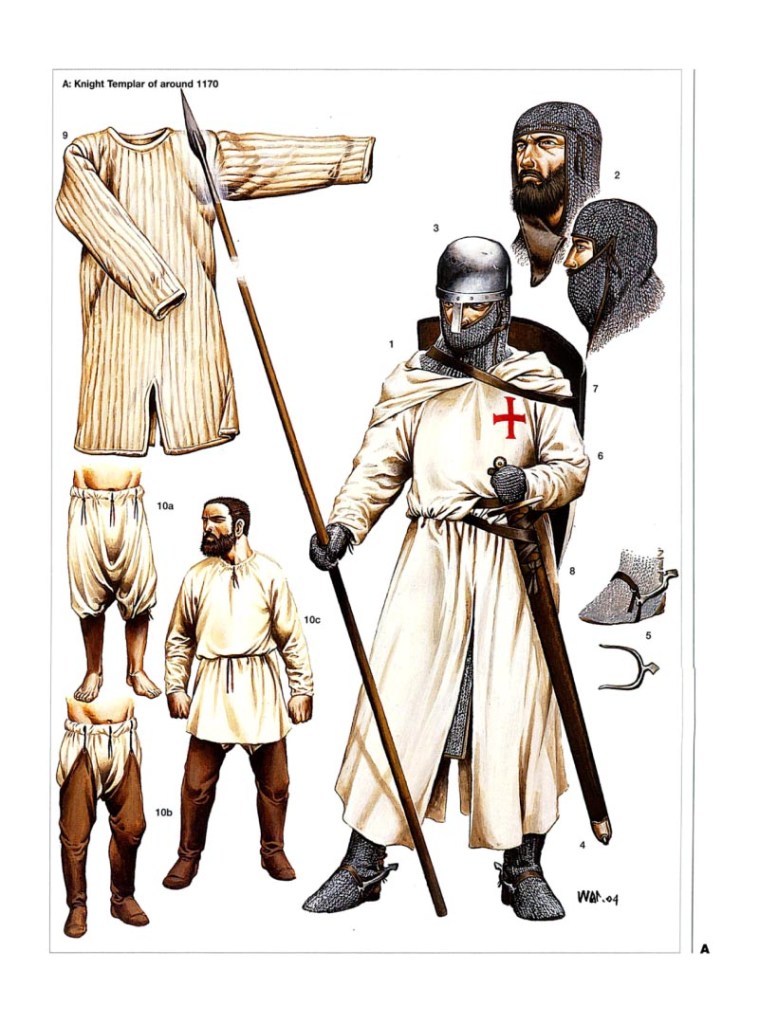

The Templars were a medieval military order much involved with the Holy Land and the Crusades,

and built nearly a thousand foundations and fortresses in their two centuries of existence. Here’s an actual preceptory (a kind of administrative center) at Balantrodoch, in Scotland, south of Edinburgh.

The order ran into trouble in the early 14th century and was disbanded by Pope Clement V in 1312, but not before state violence against some of its members, including some burned at the stake.

Because of this trouble, the “Templars” (they take that name from their capitol in Jerusalem, which they claimed was perched on top of Solomon’s temple—for more about them, see this very detailed WIKI article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knights_Templar ) gained a certain dark reputation and we might imagine that the anonymous scholar’s request to Parkins already suggests something different for him on his vacation than he had planned.

Off he goes, however, to academic work and golf, but (literally) stumbles on the remains of the preceptory and discovers a little bronze whistle at the site

with two inscriptions on it in Latin. He appears unable to translate the first, but the second says: “Quis est iste qui venit”—“Who is that one who comes (or “has come”, depending upon the sound of the e in venit).” As he turns to go back to his hotel, he notices a odd figure behind him, “in the shape of a rather indistinct personage in the distance, who seemed to be making great efforts to catch up with him, but made little, if any, progress.” This makes Parkins vaguely uneasy, but he proceeds to the hotel and dinner.

In fact, he should have paid more attention to the first inscription, which reads, almost in the form of a puzzle:

fla

fur bis

fle

“Thief—you will blow, you will weep”.

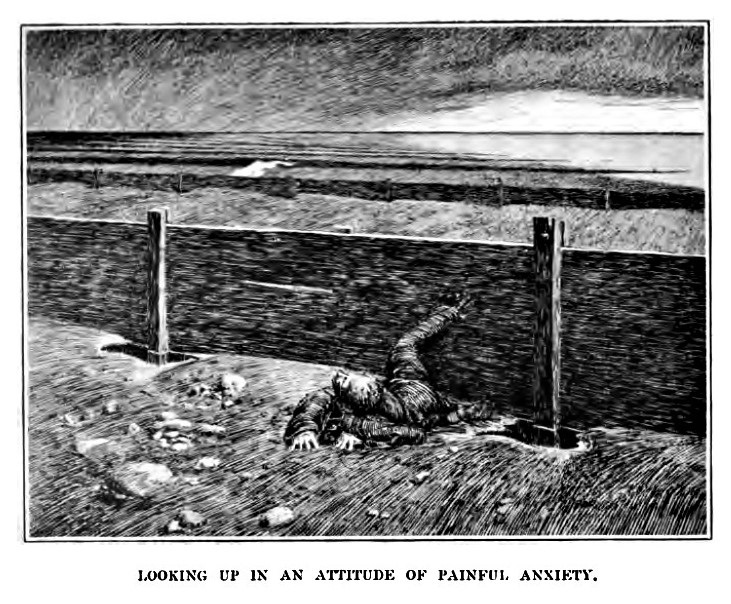

I don’t want to spoil the story for you, but, needless to say, Parkins cleans and blows the whistle and things begin to happen, things particularly unexpected by a man who has declared that he doesn’t believe in the supernatural. I’ll add the two original illustrations from the 1904 publication to give you a hint—

And I’ll add one caution: don’t expect obvious violence (although others of James’ stories have such an element)—what happens is, to my mind, not shocking, but eerie, a word which comes to us probably through Scots and has this, among other definitions, in The Scottish National Dictionary: “an undefined sense of fear; dread” (see: https://dsl.ac.uk/entry/snd/eerie ). This undefined dread makes this one of my favorite stories of this sort (though I don’t read it too often, remembering the first time I did, and the two days of such dread I felt afterwards). Read it here: https://archive.org/details/ghoststoriesana00jamegoog and see if you agree with what James wrote in his preface:

“The stories themselves do not make any very exalted claim. If any of them succeed in causing their readers to feel pleasantly uncomfortable when walking along a solitary road at nightfall, or sitting over a dying fire in the small hours, my purpose in writing them will have been attained.”

Will you, too, be creeped out?

Stay well,

Remember that fiends of any sort can’t cross running water,

(this is from a series of wood carvings of Robert Burns’ “Tam O’Shanter”, c.1860 from a great website: https://monsterbrains.blogspot.com/2015/10/thomas-hall-tweedy-tam-oshanter-wood.html )

And remember, as well, that there’s always

MTCIDC

O

PS

Does it also suggest something vaguely sinister that James’ preface is dated “Allhallows’ Eve”?