Dear readers, welcome, as always.

Aquila muscas non capit, una hirundo ver non facit, ignis aurum probat, festina lente!

Or, “an eagle doesn’t catch flies, one swallow doesn’t make spring, fire tests [the] gold, make haste—slowly!”

It might be easy to wonder whether this was going to be a posting on riddles, but, in fact, as the title suggests, it’s about much knowledge packed into a few words—which is, in fact, like Bilbo’s riddle:

“A box without hinges, key, or lid,

Yet golden treasure inside is hid.”

(The Hobbit, Chapter Five, “Riddles in the Dark”)

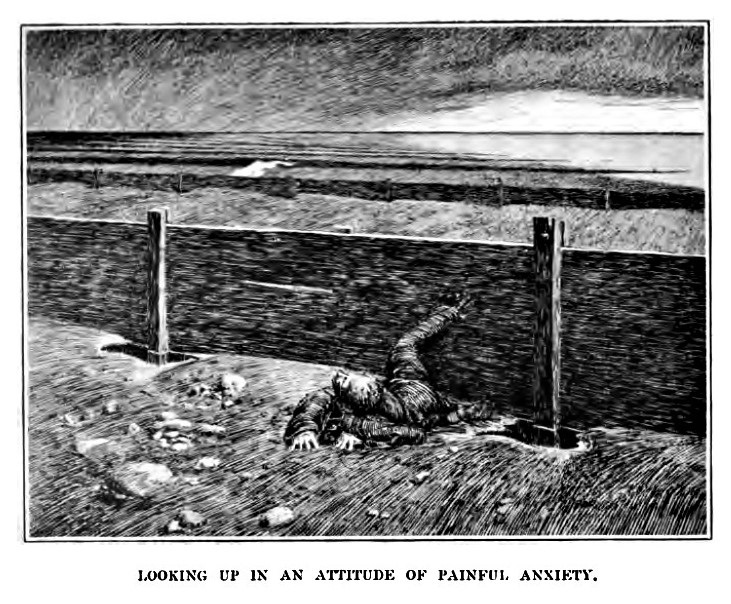

and which appears to be a bit of a poser for his sinister fellow player–

(Alan Lee)

“This [Bilbo] thought a dreadfully easy chestnut, though he had not asked it in the usual words. But it proved a nasty poser for Gollum. He hissed to himself, and still he did not answer; he whispered and spluttered.”

Gollum was, in fact, only saved by Tolkien’s joking allusion to a proverb which Douglas Anderson in The Annotated Hobbit quotes from Francis Grose’s (1731-1791) A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, 1785, as, “Go teach your granny to suck eggs; said to such as would instruct anyone in a matter he knows better than themselves.”

(You can read it for yourself here: https://archive.org/details/aclassicaldicti01grosgoog/page/n114/mode/2up in the 3rd, 1796, edition. If you’re a dictionary reader, this is simply a fun book, “learned”—hence “A Classical Dictionary”—and occasionally witty—see “Grave Digger” just below. The advertisements at the front are also very tempting, being things like The Scoundrel’s Dictionary. Grose’s A Provincial Glossary, 1787, available in the 1790 edition here: https://archive.org/details/provincialglossa00gros/page/n5/mode/2up is subtitled, with a COLLECTION of LOCAL PROVERBS and POPULAR SUPERSTITIONS and is full of interesting bits and pieces on language and belief. Grose himself is a wonderful example of the 18th-century English Antiquarian and you can read something about his adventures and collecting here, including his friendship with Robert Burns: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Grose Much of Grose’s antiquarian work is available at the Internet Archive—an institution of which Grose himself would have been fascinated, I think. Charles Dickens’ had his own opinion of such early sometime-archeologists/scholars of the past, which you can read here in Chapter XI of the 1868 edition of The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, 1836-37: https://archive.org/details/pickwickpapers02dickgoog/page/n216/mode/2up )

Tolkien was having fun with that proverbial expression (like his explanation of the creation of the game of golf in Chapter One), yet it gave Gollum the answer:

“But suddenly Gollum remembered thieving from nests long ago, and sitting under the river bank teaching his grandmother, teaching his grandmother to suck—‘Eggses!’ he hissed. ‘Eggses it is.’ “

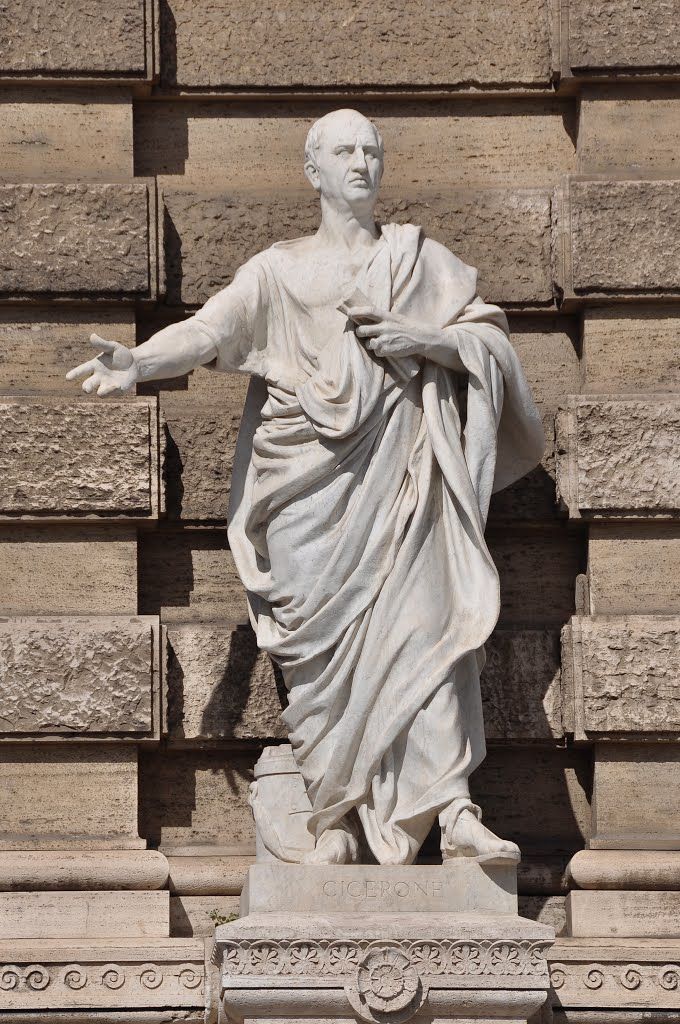

The subject of proverbs is enormous–the Latin proverbs (even the word is Latin, through Old French—pro—“before/in front/forward” and verbium—“speech act”, so “a speech put forth”, to use another old word) at the beginning of this posting are just a tiny fraction of such verbal wisdom preserved from all over the world, in the West surviving first in The Maxims of Ptahhotep

of the 12th Dynasty (basically 2000 to 1800BC—you can read about them here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Maxims_of_Ptahhotep ) and passing through the book of Proverbs in the Hebrew/Christian Bible (much scholarly argument about dating—900-300BC?) through lines in Greek tragedies, often as end-tags like “Look upon no man as fortunate until his life has come to its full circle” (Sophocles, Oidipous, 1528-30—my—very loose—translation), up to Old English works which Tolkien would have known well, like the 11th-century Durham Proverbs and the 12th-century Dicts of Cato, and it’s clear that his creation, Bilbo, has a knowledge of such things, seeming to apply them commonly when something unpleasant is to be done, and often attributing them to his father.

As Thorin attempts to push Bilbo into exploring down the tunnel from the back door towards Sauron’s lair, Bilbo replies:

“ ‘If you mean you think it is my job to go into the secret passage first…say so at once and have done! I might refuse. I have got you out of two messes already, which hardly were in the original bargain, so that I am, I think, already owed some reward. But ‘third time pays for all’ as my father used to say…” (The Hobbit, Chapter 12, “Inside Information”)

and he repeats this in the next chapter, prefacing it with a second proverb:

“ ‘Come, come!’ he said. While there’s life there’s hope!’ as my father used to say, and ‘Third time pays for all.’ “ (The Hobbit, Chapter 13, “Not At Home”)

To which he has already added a third:

“ ‘Every worm has his weak spot,’ as my father used to say, although I am sure it was not from personal experience.’ “ (The Hobbit, Chapter 12, “Inside Information”)

Not only does Bilbo know a proverb or two, however, but he even, inadvertently, creates two.

In Chapter Five (with its own proverbial title, “Out of the Frying-pan Into the Fire”), we find Gandalf, the dwarves, and Bilbo trapped in trees with Wargs about to keep them there and Bilbo shouts:

“ ‘What shall we do, what shall we do!’ he cried. ‘Escaping goblins to be caught by wolves!’ he said—“

to which the narrator adds:

“…and it became a proverb, though we now say ‘out of the frying-pan into the fire’ in the same sort of uncomfortable situations. “ (The Hobbit, Chapter Five, “Out of the Frying-pan Into the Fire”)

In Chapter 13, Bilbo, barely escaping from Smaug’s flames, says to himself:

“ ‘Never laugh at live dragons, Bilbo you fool!’ he said to himself…”

and the narrator, commenting, says:

“…and it became a favorite saying of his later, and passed into a proverb.”

(The Hobbit, Chapter 12, “Inside Information”)

To which we might imagine the hint of two more, both within a sentence of each other in the last chapter of the book. Gandalf and Bilbo have left Rivendell, their faces to the west:

“Even as they left the valley the sky darkened in the West before them, and wind and rain came upon them.

‘Merry is May-time!’ said Bilbo, as the rain beat into his face, ‘But our back is to legends and we are coming home.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 19, “The Last Stage”)

Many proverbs rhyme, as does Bilbo, in fact, surprising Gandalf, so could that first remark become something like,

“Even when sky is nothing but grey,

Still we may say, merry is May”?

and the second,

“Legends and heroes go and may come,

But now at the end, nothing’s better than home.”

Thanks, as always, for reading.

Stay well,

Strive to become legendary,

And remember that there’s always

MTCIDC

O

ps

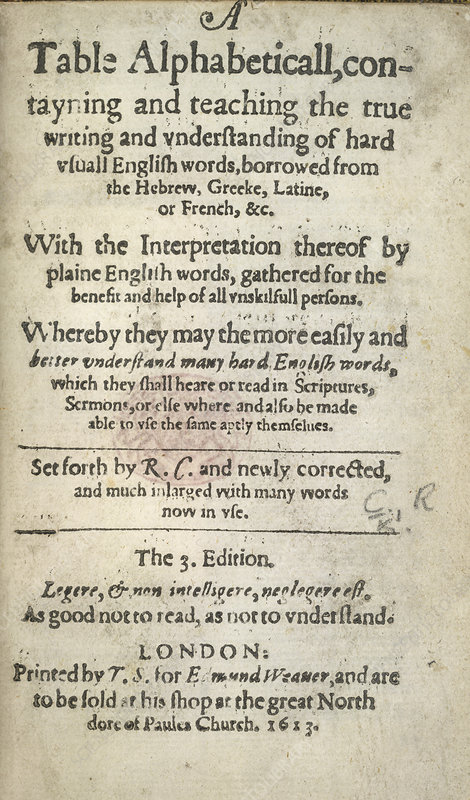

For a quick history of collections of English proverbial literature, see: W. Carew Hazlitt, English Proverbs and Proverbial Phrases, 1882, at https://archive.org/details/englishproverbs00hazlgoog/page/400/mode/2up (this is the 1907 edition) and, on the page at the link—400—you’ll also find:

“Teach your grandame to grope her ducks/to spin/to suck eggs/or to sup sour milk” as well as a Latin equivalent, Aquilam volare, delphinum notare doce—“teach [the] eagle to fly, [the] dolphin to swim”