Welcome, dear readers, as always.

In the previous posting, I began to discuss a common folktale motif, called “The Kyffhaeuser motif” or “the king under the mountain”, “the king asleep in the mountain” and several more titles as well. The basic idea is that a culture hero, rather than die, either naturally, or after battle, say, disappears to a distant place and remains there, usually asleep, until awakened by the need of his people or country, when he will reappear as a savior. (For more on this, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King_asleep_in_mountain )

Western heroes include everyone from Charlemagne to the Irish hero Finn Mac Cool to King Arthur, who, although seemingly mortally wounded, was carried off to the Isle of Avalon to be restored, with the possible suggestion that he will return, like the others in the pattern, if needed.

We know that Tolkien came to have rather mixed feelings about Arthurian material. Humphrey Carpenter says that, as a child, “The Arthurian legends also excited him”, Carpenter, Tolkien,24), but Tolkien himself later wrote: “Of course there was and is all the Arthurian world, but powerful as it is, it is imperfectly naturalized, associated with the soil of Britain, but not with English…for one thing its ‘faerie’ is too lavish, and fantastical, incoherent and repetitive.” (letter to Milton Waldman, “probably written late in 1951”, Letters, 144). Even saying so, he embarked, in the 1930s, on his own Arthurian poem “The Fall of Arthur”, eventually abandoned. Christopher Tolkien published the manuscript with commentary in 1985 (you can read about it here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Fall_of_Arthur ).

This is one Tolkien work which I have yet to read, but, judging from summaries, it appears that it breaks off before Arthur’s end. That JRRT was aware of the folkloric tradition of Arthur can be seen, however, in a letter to Naomi Mitchison, in which he discusses the ultimate fate of mortals like Frodo and Sam, who are allowed to travel to Valinor, he mentions that other possibility for Arthur:

“…this is strictly only a temporary reward: a healing and redress of suffering. They cannot abide for ever, and though they cannot return to mortal earth, they can and will ‘die’—of free will, and leave the world. (In this setting the return of Arthur would be quite impossible, a vain imagining.” (letter to Naomi Mitchison, 25 September, 1954, Letters,, 198-199)

And there is another way in which, perhaps, we can see a small Arthurian/folklore influence upon Tolkien, even to one other name for Thompson’s Kyffhaeuser motif, “The King Under the Mountain”.

When Bilbo and the much-battered dwarves seek to gain admittance to Lake-town,

(JRRT)

Thorin announces to the startled guards at the gate that he is “Thorin son of Thrain son of Thror King under the Mountain. ..I have come back.”

He subsequently repeats this to the Master and his court: “I am Thorin son of Thrain son of Thror King under the Mountain! I return!” (The Hobbit, Chapter 10, “A Warm Welcome”)

And here we can see JRRT slip right into the second part of the motif, the return of the hero:

“Some began to sing snatches of old songs concerning the return of the King under the Mountain; that it was Thror’s grandson not Thror himself that had come back did not bother them at all. Others took up the song and it rolled loud and high over the lake:

The King beneath the mountains,

The King of Carven stone,

The Lord of silver fountains

Shall come into his own!

His crown shall be upholden,

His harp shall be restrung,

His halls shall echo golden

To songs of yore re-sung.

The woods shall wave on mountains

And grass beneath the sun;

His wealth shall flow in fountains

And the rivers golden run.

The streams shall run in gladness,

The lakes shall shine and burn,

All sorrow fail and sadness

At the Mountain-king’s return!”

As for the savior part of this motif, something is implied, rather than stated: the reason that there is no current king is that the last one was driven out by Smaug, after killing (and presumably eating) many of his people.

(JRRT)

If the king is really to return, then, he must deal with the current occupant. The Master of Lake-town, who, at first, cynically welcomed the dwarves, “but believed they were frauds who would sooner or later be discovered and be turned out” then appears to change his mind and “…wondered if Thorin was after all really a descendant of the old kings”. Still cynical, however, he tells Thorin “What help we can offer shall be yours…” even while thinking, “Let them go and bother Smaug, and see how he welcomes them!”

Although the return of the king does not turn out quite as the Master—or the dwarves—expected, Smaug dying after destroying Lake-town,

(JRRT)

still, even after Thorin’s death in the Battle of the Five Armies, he remains what he claimed to have been as” They buried Thorin deep beneath the Mountain, and Bard laid the Arkenstone upon his breast.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 18, “The Return Journey”)

(Alan Lee)

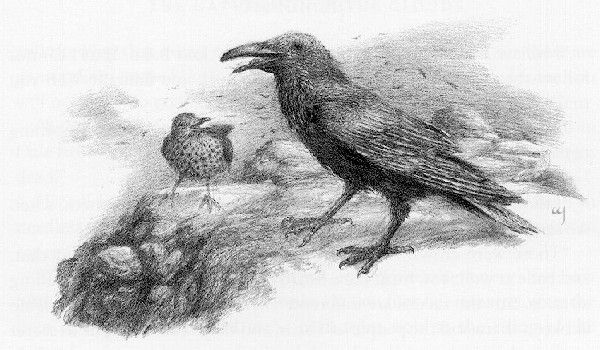

But, in the previous posting, I mentioned ravens.

(I include this just as much because it’s such a beautiful image as it’s relevant…)

The Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick I, called “Barbarossa”, is one of the many heroes who appear in a version of “the king under the mountain” and, among the variants told of him is this one, to be found in the Grimm brothers Deutsche Sagen, (“German Legends”) where it’s reported that when a dwarf led a shepherd under the mountain, Barbarossa stood up and asked, “Are the ravens still flying around the mountain?” At the shepherd’s affirmation, he cried, “Now must I sleep yet a hundred years longer!”

(Brothers Grimm, Deutsche Sagen, Number 23, Vol.1, page 30, my translation. You can find the text here: https://books.google.com/books?id=SRcFAAAAQAAJ&pg=PR1#v=onepage&q&f=false )

After Smaug has flown off to Lake-town and his doom, the dwarves and Bilbo emerge from the Lonely Mountain, where they are met by the same thrush which had helped in finding and opening the back door, as prescribed in the moon letters on Thror’s map.

He twitters excitedly at them, but they can’t understand him and Balin exclaims, “I only wish he was a raven!”

When Bilbo replies, “I thought you did not like them! You seemed very shy of them, when we came this way before.”

To which Balin responds:

“Those were crows! And nasty suspicious-looking creatures at that, and rude as well. You must have heard the ugly names they were calling after us. But the ravens are different. There used to be great friendship between them and the people of Thror; and they often brought us secret news, and were rewarded with such bright things as they coveted to hide in their dwellings.” (The Hobbit, Chapter 15, “The Gathering of the Clouds”)

The thrush flies off and an ancient raven appears, Roac, son of Carc, who says to Thorin:

“Now I am chief of the great ravens of the Mountain. We are few, but we remember still the king that was of old.”

Did Tolkien know this legend? If you consult indices to both Carpenter’s biography and his edition of Tolkien’s letters, there is no trace to be found there under everything from “Barbarossa” to “raven” and yet the confluence of “king under the mountain” and that mountain hosting ravens would seem suggestive, I think. Or perhaps a little bird told him…

(Alan Lee)

As ever, thanks for reading.

Stay well,

When a raven speaks, it’s wise to listen,

And remember that, as always, there’s

MTCIDC

O

PS

Which reminds me of a famous old ballad, “The Three Ravens” (Child Ballad #26) which you can read about here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Three_Ravens and listen to here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T8ZASCwSRN0